World

Iran-Saudi Arabia Rapprochement Part-II: History Repeats Itself

- Implications of Saudi-Iranian rapprochement in Beijing, was explained in the Part-I of this series.

- Here's Part-II explaining how the current flux triggered by the Beijing agreement could reaffirm an old dictum — that artificially high prices are unsustainable in a glut.

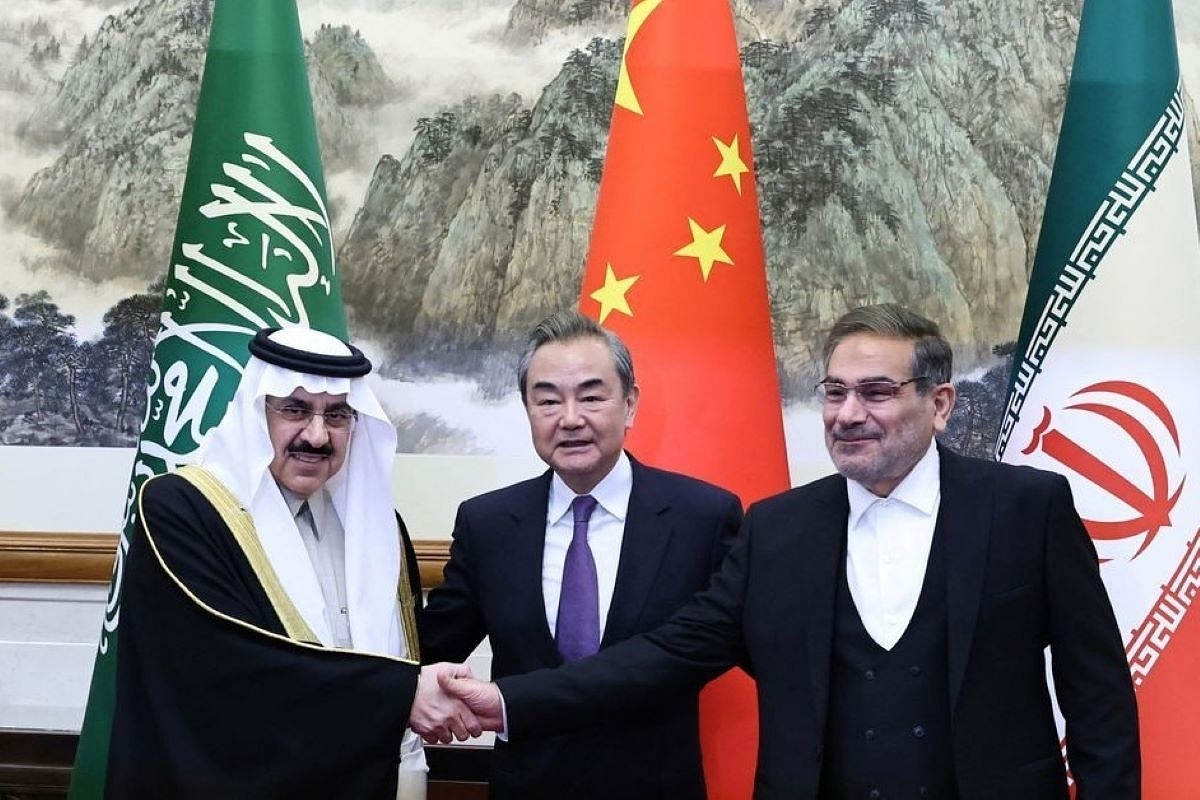

Leaders of Saudi Arbia, China and Iran.

A recent decision by Iran and Saudi Arabia to resume diplomatic relations has ruffled a number of feathers in America (Read the article on Swarajya here).

In addition, the fact that these momentous talks were brokered by China, in secret, in Beijing, has made the already-paranoid view this development through a sinister lens.

Investors and analysts were quick to declare that Saudi Arabia was playing with fire by casting its lot with Iran and China. Never ones to be left behind, loyal brown sepoys in India’s mainstream media also obediently echoed such alarm.

Yet the truth beyond the clamour is that, this is history repeating itself. It is the only way the world’s major oil exporters can climb out of a prevailing oil glut. They did it before, and they’re doing it again.

For most of the 20th century, the Middle East was firmly under America’s thumb, and dutifully supplied the bulk of the world’s oil needs. But then in the 1970s, these long-established dynamics were altered dramatically for two reasons.

One was the twin oil shocks of 1973 and 1979, when the Middle East first rebelled against the West. This led to price spikes, a reduction in demand, and a move towards energy conservation as an article of faith in the West.

Consequently, the tremendous post-war growth in oil consumption levels started to taper off.

The second event was a surge in oil production during the 1970s in areas other than the Middle East.

Year after year, new discoveries driven by new technologies meant that millions of barrels of oil began to enter the market from new basins in the North Sea, China, Malaysia, India, Alaska, Russia, Australia, and elsewhere.

By the 1980s, the world was in the midst of an oil glut, and prices started to drop.

The only way prices could be shored up was if the Middle East cut oil production. For that, Saudi Arabia started to unilaterally cut output. This was the first accommodation of new players in the oil game.

From over 10 million barrels a day (MMbopd) in 1981, Saudi Arabia selflessly brought output down to under 4 MMbopd in 1985.

Unfortunately, however, Riyadh’s altruism received only ingratitude in return, as new producers greedily raced to fill that gap. As a result, the oil price continued to fall.

Then, in the summer of 1986, a frustrated Saudi Arabia decided to end its self-imposed curtailments of oil production, and opened its valves. The oil price dropped like a stone by three quarters, from $45 to $10.

It was a price war no one could win, since Saudi Arabia’s low production costs, and the capacity it had in reserve, was unmatchable.

The new producers were left without a floor to stand on, better sense prevailed, and the oil price began to rise again, in step with a return of Saudi oil production back to pre-glut levels.

The breakpoint in 1986 is clearly visible on an oil price chart below.

Now fast-forward to 2023. What is the global oil situation today?

The world is once again in the midst of an oil glut. Demand growth is sluggish.

Russia and Saudi Arabia continue to maintain high levels of production. And, as a chart above shows, the age of the new producers is on the wane; oil production is declining in Europe and Asia.

But there is a difference: America and Canada have combined to more than double the oil production.

Most of this is expensive ‘shale oil’ from unconventional plays which needs two factors to survive: a minimum oil price band of $60-$70, and a piece of the market.

To this end, America has sought to truncate oil production from a number of exporters ever since the shale oil boom began two decades ago, either through sanctions, or by engineering conflicts.

The list includes Venezuela, Libya, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, and even Sudan (remember George Clooney’s Darfur speech of 2006?).

Just look at how Venezuela’s oil industry, and its economy with it, was systematically demolished by American sanctions, so that market space could be opened up for the latter’s shale oil:

This is the second accommodation, and like in the 1980s, it has triggered a second revolt against America by the Saudis.

One major difference is that this time, they are not alone; Russia, Iran, Iraq, and Oman too, seek to regain higher levels of oil supply to markets from which they have been persistently edged out of by costly American shale oil.

Another difference is that the major importers do not want to have anything to do with this tussle between the two exporters groups; they just want the best long term deals they can get.

And in that, pertinently, a third difference is that the list of major importers has changed since the 1980s. Today, India and China together import more crude than Europe and Japan combined. And in a glut, when it is a buyer’s market, it is they who set the rules.

As a result, if the past half century was one of the swing producer, then this era belongs to the swing consumer. For example, if China and India were to buy half their oil from America, at least two or three of the traditional oil majors would face economic doom.

Conversely, and germane to the Saudi-Iranian agreement signed in Beijing last week, if the Middle East and Russia were to cut oil prices and increase output, the American shale oil industry would come to a juddering halt.

Obviously, neither extreme example is going to come to pass, because of the fractious geopolitics which prevails.

India doesn’t get on with China, who doesn’t get on with America, who doesn’t get on with Russia, and so on.

But the threat of both extremes remains, which is why, on the one hand, investment in the American shale sector remains cautiously low, and on the other, why India and China have blithely increased oil imports from Russia in spite of Western sanctions on Moscow.

And, at some point of time, Europe too, will have to choose, because it is not just about oil; there’s gas as well.

Thus, in conclusion, the current flux triggered by the Beijing agreement could lead to increased oil production from the Middle East, their purchase in higher volumes by oil importers, erode the isolation sought to be imposed on Russia and Iran, place a strain on American shale oil viability, and reaffirm an old dictum — that artificially high prices are unsustainable in a glut.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest