Books

A Biography of Bengaluru – From Kempe Gowda’s Dream City To Silicon Valley Of India And Beyond

Book Excerpts

Aug 16, 2017, 07:08 PM | Updated 07:08 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

When Kempe Gowda set out to build the city of Bengaluru, his mother is said to have told him “keregalam kattu, marangalam nedu” – build lakes, plant trees.

Were he to revisit the city today, he would sadly be appalled at what this great city has become.

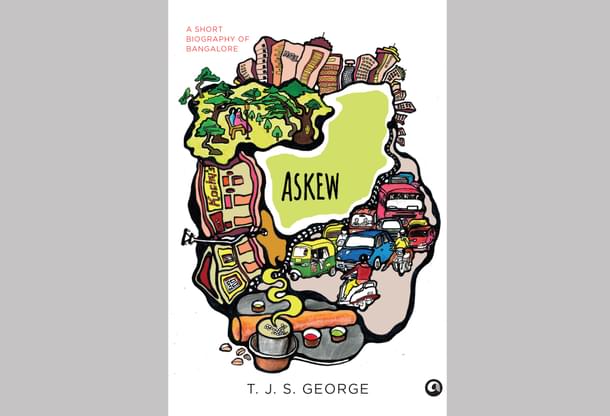

This journey of Bengaluru – from being a pensioner’s paradise to the Silicon Valley of India and beyond – is the subject of author T J S George’s latest book, ‘Askew: A Short Biography of Bangalore’.

Here’s an excerpt from the book which looks at a defining feature of the city, one that changed its face and fate forever, the information technology revolution.

Bangalore had etched a narrative of growth at its own pace, producing silk and cotton, then branded beer and rum, and then public sector watches, machine tools and telephone accessories. But information technology changed the nature of the narrative, changed even the city’s name from a noun to a verb; Barack Obama publicly objected to American jobs being Bangalored.

The hype and triumphalism of IT’s unstoppable march led many to believe that the industry had sprouted in the city by happenstance. Actually, history and planning had combined to develop Bangalore, unnoticed at the time, into a hub of futuristic growth.

Tipu Sultan himself started it. As early as the 1780s his engineers had invented rocketry, terrorizing the British. The colonizers on their part chose Bangalore as the headquarters of the oldest of the three engineeringgroups of the British Indian Army—the Madras Sappers. It was this centre that developed the Bangalore Torpedo, a mine-clearing weapon used in the First and Second World Wars and still in the armoury of many armies.

Diwan Seshadri Iyer began harnessing waterfalls and in 1904 Bangalore became the first Indian city to have streets lighted by electricity. Sir M (as Diwan M. Visvesvaraya was popularly known) did the rest with his slogan ‘Industrialize or Perish’. He invited Walchand Hirachand to start Hindustan Aircraft Factory, today’s HAL, in Bangalore. He also persuaded Jamshetji Tata to set up the (Tata, and later Indian) Institute of Science on 371 acres of land contributed by the Maharaja of Mysore. That turned Bangalore into a focal point of advanced scientific research.

C. V. Raman, who became its first Indian director, later opened his own Indian Academy of Sciences and the Raman Research Institute a few kilometres away. When India began its pioneering space programmes, Bangalore became the headquarters of ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation). A hundred engineering colleges also sprouted in the city in a span of a few years.

Trained manpower, an English-speaking environment, availability of land and pleasant weather were in place waiting for the wunderkinds of the world. Then a small company named Infosys, founded in Pune in 1981, moved to Bangalore. In 1982 a Maharashtra-based family-owned vegetable oils trader of pre-Independence vintage decided to diversify, and opened its headquarters in Bangalore as Wipro. Few paid attention to these unfamiliar companies doing unfamiliar things. That is, until a well-known American multinational, Texas Instruments, set up a branch office in Bangalore with a name board so prominently positioned that no one on the way to or from the airport could possibly miss it. Suddenly attention was drawn to Bangalore spearheading a New-Age business revolution involving chips and circuits and sequencing and programming.

Before anyone knew what was happening, Bangalore became the global leader in Business Process Outsourcing. The world quickly realized that skilled staff at salaries of one-quarter to one-tenth of standard rates in the West was not Bangalore’s principal attraction—wunderkinds abounded in the region capable of handling any challenge from any quarter.

Companies like Intel, Microsoft and Cisco Systems picked the city for their advanced R&D projects. An army of whizz-kids soon emerged to turn Bangalore into India’s start-up capital as well. Bangalore acquired a newly prosperous, even bohemian, aura.

The speed at which information technology altered the sociology as well as the economy produced an inevitable backlash. While intellectuals such as U. R. Ananthamurthy cautioned about newly created problems of identity, local activists questioned what was Bangalore and who was a Bangalorean. There were campaigns for jobs for Kannadigas. There were protests against Hindi signboards.

The problem was that IT transformed Bangalore in ways earlier bouts of industrialization and immigration had not. The old agreeable Bangalore was now replaced by an aggressive Bangalore where no one had time for his neighbours. Everyone was chasing success as measured by a new consumerist value system.

A gladiator culture took over with the spirit of combat as its perennial feature. If the pre-IT immigrants made an effort to merge into Bangalore, the new combatants were too disparate to try. They remained Punjabis, Rajasthanis, Gujaratis and UP-Biharis, Americans,Canadians, Europeans and Latin Americans, Africans,Middle Easterners, Japanese, Koreans and Thais. What overwhelmed Whitefield and Sarjapur were only the high points of what plagued Bangalore as a whole. Cosy Town turned international melting pot, Bangalore’s face turned ugly.

California’s Bay Area did not lose its charm when Silicon Valley became a land of miracles. Neither did Boston. Why did modernity and enterprise make Bangalore unbearable? The answer was that Bangalore’s elected leaders, administrators and builders disobeyed Kempe Gowda’s mother. When the fabled founder of Bangalore set out to build his dream capital in the 1530s, his mother gave him two instructions: ‘Keregalam kattu, marangala nedu (Build lakes, plant trees)’. Gowda made a hundred lakes and lined the pathways with wide, leafy trees.

Politicians and land dealers of modern times were born to different kinds of mothers. In about three decades they filled up 2,000 hectares of lakes, and, in the late 2000s alone, felled 50,000 trees. Under their earth movers and power saws, the urban sprawl expanded until the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) became the largest municipal corporation in the country.

The population density rose to 12,000 persons per square kilometre. The Bangalore Development Authority’s Revised Master Plan estimated that the population count would cross 20 million. Small wonder then that in Electronic City land prices rose by 300 per cent in about ten years. According to popular statistics, Bangalore had more potholes and dangerous medians per kilometre than any other city. Two of them were patched up by the authorities. In June 2015, artist Baadal Nanjundaswamy noticed a water-filled pothole, unusually large even by Bangalore standards, in the crowded Sultanpalya area.

He painted its edges in greens and blues, planted a few blades of grass in strategic spots and then brought in a life-size rubber crocodile to frolic in the water. A year earlier Nanjundaswamy was appalled by the sight of a road median the detached granite blocks of which had become a danger to motorists. He turned that too into an art installation, the granite blocks shining in bright colours with flower stalks and green leaves growing out of them. Locals gathered to admire the street art on both occasions. Municipal authorities moved in fast, filled the pothole and straightened the median. Citizens who criticized them for being anti-art were pacified by those who pointed to the reassuring sense of shame displayed by the authorities. Through it all Bangalore acquired more than a hundred slums accommodating 2 million people.

New-Age gladiators appeared from nowhere and from everywhere to take care of slum management and allied businesses. In 2014, Bangalore ranked second in the number of murders (Delhi was first), third in robberies (after Delhi and Bombay) and third in dacoity cases (after Pune and Delhi).

In this urban demographic nightmare, it was inevitable that group rivalries, linguistic antagonisms and cultural confrontations would become a part of life.

Excerpted from Askew: A Short Biography of Bangalore by T J S George, Aleph Book Company, 2016 , with the permission of the publisher.