Books

Break Free of the Past for Swarajya 2.0

Gautam Mukherjee

Dec 27, 2014, 05:27 PM | Updated Feb 24, 2016, 04:20 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

We now have a young and aspirational polity, demanding economic betterment without excuses. But socialist ideological moorings are still holding us back, though the knots may indeed be loosening at last.

Lokmanya Tilak coined the term Swaraj near the turn of the 19th century. He used it to epitomise the yearning for independence, centre-piecing it in his wonderful assertion that it was his birthright, and paying for it by being whisked away to Burma for six long years.

Rajagopalachari or Rajaji, the eminence grise behind the first avatar of this publication, coming further down the pike, in the 20th, put his finger on a major malaise of socialist India, coining the apt descriptor: ‘Licence-Permit Raj’.

Today, in the 21st, the meaning of Swarajya has turned metaphorical; it may well embody the growing yearning for economic progress, finally stripped of its socialist fetters. The spirit of Rajagopalachari, our first Governor General, founder of the brave—given the times—and farsighted Swatantra Party, putative ‘conscience keeper’ to the Mahatma, may be getting all set to ride again.

But Swarajya, ‘in our own write’, is hard to come by. Those socialist ideological moorings are still holding us back, though the knots may indeed be loosening at last. We now have a young and aspirational polity, demanding economic betterment without excuses.

Even then, the din and intellectual confusion of a retrogressive clinging, the yesterday-men howling and lamenting their loss of power, tell us that we are still a long way from home. This, despite the decisive installation of a right-of-centre BJP government with a clear majority.

And the announcement of a host of measures in the offing, including the raising of the foreign participation limit in indigenous defence production to at least 49 per cent, the delicensing of several categories, and even agreeing to a 100 per cent foreign ownership on a case-by-case basis.

There are many other sparklers in the works: billions in foreign investment from Japan and China to be invested in renewing the Indian Railways, fast and faster bullet trains, Russian diamonds to be sold directly to Indians, helicopters to be manufactured here, a dozen new nuclear plants to generate electricity, PSU bank privatisation up to 48 per cent, divestment of other PSU shares to raise over Rs 60,000 crore for the government coffers, raising the FDI limit in insurance to 49 per cent to bring in more than $10 billion in investment, implementation of a GST to raise the GDP by up to an estimated 1.7 per cent, the scrapping of some 90 redundant laws, solar power, clean rivers, efficient governance, and so on.

Never has a Government of India attempted to do so much to get the economy moving again in such a short time since its advent. But many of these things are meeting with enormous resistance on their way to implementation―by a fragmented but disruptive Opposition. The Opposition is also panicking, and consequently more strident. It is despairing of being pushed into oblivion by the ruling party’s blitzkrieg of electoral success, ongoing in the assemblies now, juxtaposed with the seeming irrelevance of their ideas that no longer resonate with the voting public.

Much of intellectual India is still, as it heads towards its 70th year since independence, ambivalent. It is shackled to isms that have been discredited globally, even by the people who still hang out the shingle. The world can see a very capitalist China for example, grown mighty as a consequence; and a little Cuba by way of contrast, emerging from a time warp, reconnecting, reconciling, re-establishing diplomatic relations with the US after half a century. But India, maddeningly, cannot quite make up its mind.

It may be instructive to note that there are very few journalists, commentators, thought leaders, willing to root for the right-of-centre point of view in India. Conversely, there are legions of the liberal-left/socialist persuasion. And indeed, an overwhelming majority of mainstream newspapers, magazines and television channels, including those in the myriad vernacular, that chime in alongside.

Is this because India has been socialist for a very long season? So much so, that its tenets are semi-embedded in our psyches, and not just peremptorily in the Preamble to the Constitution.

And many influencers, smarting unbelievingly still, from the loss of their pole positions under the earlier Government, aver, quite subversively, that the very idea of India, as it was conceived―pluralistic, inclusive, secular, diverse, etc―is being subordinated to a majoritarian agenda. There may be strands of justification for this stance, with frequent and bizarre sallies from the Sangh Parivar’s fringes, but it should not turn them against the BJP’s robust economic plans. But here too, there is a ‘communal’ bogey, an accusation, implicit, and an assertion that growth on the changed terms of a ‘level playing field’ cannot compare to one that clearly purports to favour and protect the minorities.

The young demographic of the voting public may be fed up of a rhetoric that does not deliver, but the bulk of the thought leaders refuse to update their spiel, hoping against hope that they can hold out for five years, before seeing this government out of the door.

But why does the liberal-left portray the centre-right in pejorative terms, 23 years after the ushering in of the first stage of reforms, that too under Congress rule? The benefits of changes made in I991, which actually began in 1985, have undeniably been transformative.

The year 1985 was when the ‘Computerji’, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi came into his own, and started dismantling the statist controls of his venerated predecessor and mother. Today, the gains of 1991 are easy to take for granted, but only for those who do not predate that particular Rubicon. Many of the intervening years have given us unprecedented growth, in near double-digits, as compared to the humiliating, almost zero ‘Hindu rate’ that preceded it.

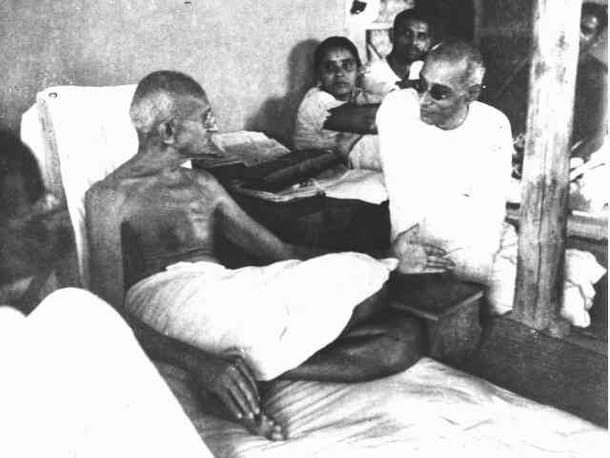

So, what gives credence to the ongoing prejudice? Is it the sheer numbers of the liberal left advocacy, its endless repetition, backed with a self-generated air of authority? Or is it because, from the days preceding Indian independence, father of the nation Mahatma Gandhi made some telling choices? Apart from his own, piquant, small-is-beautiful and back-to-the-village ideas, he chose the then fashionable Fabian socialist leanings of the urbane, young, and personable Jawaharlal Nehru. He did this over the hard-bitten and largely self-evident free-market philosophies of other stalwarts such as Rajaji, Rajendra Prasad and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

That these laissez faire principles, albeit with a massive imperialist bias, served the Raj and the East India Company for centuries before, was probably the telling black mark. It was, after all, a thriving and vibrant commercial philosophy. But the post-colonial world could muster no love for the free market because it did nothing proactive about the subjugation of the weak and poor. So policy makers emerging from the foreign yoke wanted first of all to promote equality and social justice. They may be forgiven for believing that socialism, or even communism, the new rage since the Russian Revolution of 1917, was indeed the answer.

Cutting to the present day, it is a mystery still, how, those we now label the LibLeft, expect to fund its give-away largesse? Except, that is, through an ever burgeoning fiscal deficit! Why concurrently are these people indifferent towards the very engines of growth that can supply the wherewithal? What is wrong with the State unabashedly supporting business, industry, FDI, FII, a balancing of budgets, and so on? Growth in GDP is not just ‘crony capitalism’, as the distortion would have it, but a boost for every sector of the economy.

The unleashing of growth since 1991 has produced spectacular results already and put India on the global economic map, even if it is past time to usher in the second stage of structural reforms. The sensex, writes Dhirendra Kumar of mutual fund advisory Value Research, was at a mere 600 in 1989, two years before the advent of first-stage reforms. It had climbed to 3,600 in 1999, and 21,600 in 2008. The BSE Sensex has been growing ‘six-fold per decade’, says Kumar. It is expected to climb to 35,000 by December 2015.

There is much foreign excitement and anticipation of a bright future for India. The upcoming Vibrant Gujarat Summit in January 2015 is promising to be another economic landmark. It will be attended by US Secretary of State John Kerry along with a delegation of 80 before President Obama himself arrives for the Republic Day. UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon will also be there, along with Bill Gates, and several heads of state. There are many proposals to establish new industry in Gujarat, including one to make Kalashnikov AK-47 rifles, in the land of the Mahatma.

The fact is, given our gargantuan and growing population, already over 1.3 billion strong, India cannot make any enduring dent in poverty without at least 8 per cent GDP growth per annum. What is needed, as demonstrated by China, are decades of sustained high growth, near or above the double- digits. But a new Swarajya 2.0 can only truly dawn when we resolve to break free of the past, and pull out all the stops for the future..

Gautam Mukherjee is a political commentator whose columns figure regularly in different right-of-centre media outlets