Books

Dharma, Dominion, And The Divine: Mapping Animal Welfare Across World Religions

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jun 01, 2025, 01:21 PM | Updated 06:59 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Animal Welfare in World Religions: Teaching and Practice. Joyce D’Silva. Earthscan from Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). Pages 274. Rs 2,841.

More than a decade ago, I was attending a conference in which a young Catholic theologian, an ordained priest, spoke about David Bohm, Francis of Assisi and evolution.

After the talk I got a chance to interact with him informally and I asked what he thought of Francis of Assisi’s views on animals having souls. He immediately corrected me telling that they have awareness, consciousness, but not souls.

It was a dualist and Christian theological nuance to separate the soul and consciousness. Dualist because it sees the physical body and hence the physical universe and soul as two entirely different essences. But that brief conversation made me realise that different religions have entirely different perceptions on non-human animals.

Joyce D’Silva, Ambassador Emeritus for Compassion in World Farming, a leading charity advancing the welfare of farm animals worldwide, in her book, Animal Welfare in World Religions: Teaching and Practice (Earthscan Routledge, 2023) provides a comprehensive and comparative study of each major religion in the world on the topic and also how the religionists adhere or deviate from the values advocated by their religion.

In her insightful review of the Jewish perspective on human-animal relationships, the author meticulously explores how Judaism, as the progenitor of monotheistic faiths, laid foundational principles that continue to resonate in contemporary discussions about animal welfare.

The core argument centers on the dual concept of human dominion over animals, balanced by a profound divine mandate for compassion, stemming from the belief that all creatures are God's handiwork.

The section on Judaism traces the ethos towards non-human animals from the Genesis creation account, where humanity's unique ‘neshama’ (spiritual soul) is highlighted, to prophetic visions of harmonious coexistence. A central theme is the principle of tsa’ar ba’alei chayim—the prohibition against causing pain to living creatures—which is shown to permeate Jewish law and thought, illustrated by compelling anecdotes of revered figures like Moses and Rebecca, and championed by influential scholars such as Maimonides.

This principle's application extends beyond mere avoidance of cruelty, encompassing concepts like Sabbath rest for animals and ethical considerations in slaughter.

The author masterfully navigates the tension between traditional practices and modern realities, particularly in the realm of industrial farming. While acknowledging Judaism's historical permission for meat consumption, the book highlights the growing number of contemporary rabbis and scholars who argue that factory farming's inherent cruelties fundamentally violate Jewish ethical tenets, propelling a significant movement towards vegetarianism and veganism within the faith.

The ongoing discourse surrounding shechita (ritual slaughter) and the ethical considerations in animal experimentation further underscore Judaism's continuous engagement with these complex issues. Ultimately, the book portrays a rich and evolving Jewish tradition that, despite varied interpretations, consistently prioritizes the compassionate treatment of all God's creatures, offering a compelling framework for understanding the intricate relationship between humanity and the animal kingdom.

The next religion that is dealt with is Christianity.

The historic evolution of the religion from its early days as a revolutionary, experiential faith to its institutionalisation within the Roman Empire is taken into account. This evolution, the author notes, led to a predominantly anthropocentric theological framework, where the welfare of animals often receded from central concern, a point frankly acknowledged by contemporary Christian scholars.

The core of the passage identifies a persistent tension within Christian thought: between a dominant tradition asserting human dominion over animals for human ends, and a minority, yet significant, strand advocating for compassionate stewardship and the inherent value of all creatures as God's creation.

The book also examines how these divergent viewpoints manifest in Christian teachings and practices. It explores symbolic animal representations in Christian art and analyses New Testament passages, revealing that while Jesus acknowledged God's care for all creatures, his teachings often prioritized human well-being.

A particularly compelling section highlights the "Franciscan school of thought," showcasing the lives of saints like Francis of Assisi and Martin de Porres, whose profound empathy for animals serves as a powerful counter-narrative to the more utilitarian perspectives. Martin de Porres was cannonised by Pope John XXIII in 1962.

Concluding with a critical look at the global impact of Christian-majority nations on animal welfare, the book cites examples like Brazil and the United States to demonstrate how economic pressures often lead to practices inconsistent with expressed Christian values. It highlights a growing movement among Christians towards plant-based diets and active campaigning against animal exploitation, driven by a renewed focus on environmental stewardship and ethical responsibility. The passage ultimately suggests that embracing the ‘Franciscan strand’ - a path of deeper compassion and recognition of animals as fellow creatures.

This is considered as representing a vital and increasingly relevant direction for Christianity, promising a reduction in suffering and a more holistic alignment with the faith's core tenets.

The books section on Islam starts with pointing out the prejudices against Islam with its stereotype of a faith lacking concern for animal welfare, contrasting it sharply with the values found in the Koran and Hadith that may be considered as dealing with non-human animal welfare. The author asserts that popular observations of animal mistreatment in some Muslim-majority countries often stem from a disconnect between practice and the explicit tenets of the faith. Towards this end she highlights a core Islamic belief that position animals as ‘communities like yourselves’ who praise God and are under divine provision, emphasising humanity's role as a kind of trustee with a sacred duty to care for all creation.

Then the author looks into the nuances of Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia) and the concept of masalih al-khalq (universal common good), which extends welfare considerations to all sentient beings. It contrasts the ideal of animals ‘enjoying’ pastures, as described in the Koran, with the realities of modern factory farming, arguing that such intensive methods implicitly contradict Islamic principles of compassion. This section critically analyses various animal uses, from hunting (permitted for necessity, forbidden for sport) to vivisection (justifiable only with pain relief for serious human/animal benefit), consistently linking these practices back to core Islamic values.

The book also addresses the contentious issue of halal slaughter, acknowledging the internal Muslim debate regarding pre-stunning and advocating for practices that align with the Prophet's instruction to ‘kill in a good way.’ The book alleges a widespread disconnect between non-human animal welfare discerned in Koran and contemporary practices in many Muslim-majority nations, particularly in industrial farming.

However, it also points to pockets of hope, such as organic farms and progressive legal rulings, concluding with a powerful call to action for Muslims to rediscover and actively implement their faith's inherent compassion for animals, advocating for stronger animal welfare laws and ethical consumption choices.

It is quite interesting to note that in 2018, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA) prohibited several practices that constitute cruelty toward animals as a royal decree and if the practices are done they can be done only with medical justification, while others are forbidden for any reason whatsoever.

When the book moves to Hinduism, the primary sources related to animal welfare visibly increase. One fails to understand why the author should spend so many passages in reinforcing a challenged narrative of Hinduism, almost essentialising it with the varna system which is irrelevant to the subject in hand. The author does not discuss crusades and witch burning with Christianity, Jihad and jaziya with Islam – rightly so. Then why begin with an elaborate passages on the questionable if not discredited Aryan theory and go into varna system?

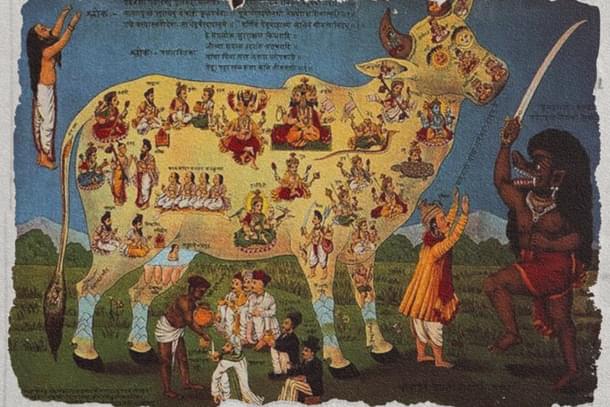

When entering the subject matter the book gets into the way Dharma views the human relationship with non-human animals, emphasising the concept of an eternal Dharma or Sanatana Dharma that underpins its approach to all life. The review delves into Hinduism's rich sacred texts—the Vedas, Upanishads, and epics like the Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita)—to demonstrate the profound Dharmic basis for animal reverence, particularly the fundamental vision of Brahman (the ultimate reality) as immanent in all creatures and the interconnectedness of all beings. The principle of ahimsa (non-violence) is presented as a cornerstone, profoundly articulated by figures like Mahatma Gandhi, who extended it to all living things and famously stated that a lamb's life is no less precious than a human's.

However, the book does not shy away from the inconsistencies between this idealistic teaching and practical realities. It highlights historical practices like animal sacrifice (though now largely diminished or banned in many places) and the paradoxical situation of revered animals like cows enduring neglect or mistreatment in modern India. The passage critically examines the severe animal welfare issues within India's intensive dairy and poultry industries, noting the widespread use of tethering, illegal oxytocin injections, and battery cages, which are depicted as direct violations of Hindu principles such as the ‘enjoyment’ of pastures and the presence of the divine in all beings. The author could have also asked some Acharyas and their Dharmic view of such practices. It should be noted that the secular Government of India with a severe propaganda de-Hinduised the Dharmic perception that was prevalent in India. What we see today is a mixed situation of of this severe propaganda and the extant Dharmic nation.

The plight of temple elephants, often chained and subjected to distress, is also brought to light as a stark contradiction to the reverence shown to the elephant-headed god Ganesha. However the author misses out the mahout-elephant relation which the Hindu India has created. This is an unique human-animal ecosystem which has Dharmic roots. In the overdrive to ‘rescue’ temple elephants this most unique system should not be destroyed.

There is a change of tone in the book where it deals with Hinduism The section is more a challenge to Hindus highlighting their spiritual teachings with their contemporary practices, particularly concerning factory farming and the ethical treatment of animals, advocating for a renewed commitment to ahimsa and compassionate action in the modern world.

In the section on Buddhism, the author is at pains to explain why, though non-theistic, Buddhism should be considered a religion. Buddhism is thus presented as a spiritual path, code of ethics, or way of life, founded on Siddhartha Gautama's profound realisation of universal suffering, encompassing all sentient beings. The author stresses the core Buddhist virtue of compassion (karuna) and loving kindness (metta), extending to all sentient beings, and highlights the Five Precepts, especially the injunction against taking life, as foundational to Buddhist ethics regarding animals.

The concept of bodhicitta—the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings—and practices like tonglen (taking on others' suffering) are presented as embodying this expansive compassion.

As with other religions, here also the author examines the gap between these lofty ideals and practical realities, noting the anomaly of animals being considered part of a "lower realm" of existence, making spiritual progress difficult, yet simultaneously acknowledging that many Jataka Tales feature animals teaching moral virtues.

The author highlights the significant influence of figures like King Ashoka, who implemented comprehensive animal protection laws, and contemporary leaders like the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh, who advocate for reduced meat consumption and compassionate living. Despite these teachings, the review exposes the widespread engagement in intensive factory farming in Buddhist-majority countries like Thailand and Japan, where economic interests often override ethical considerations. Practices such as cockfighting in Thailand and the dolphin and whale hunts in Japan are explicitly presented as stark contradictions to Buddhist principles of non-violence and universal compassion.

The author points to existing regulations in Buddhist-majority nations that aim to reduce suffering in laboratories, but implies that more stringent adherence to core Buddhist ethics would lead to a significant reduction, if not abolition, of most animal testing. The section on Buddhism concludes by exhorting Buddhist leaders and practitioners to bridge the gap between their compassionate teachings and prevalent animal exploitation, urging for a more consistent and outspoken advocacy for animal welfare globally.

Now the author deals with the 'minor' religions (because of the lower number of adherents compared to the dominant five religions) and also the indigenous faiths of the ‘first nations’ in continental lands like Australia etc.

Here the book highlights that while Abrahamic faiths may place humans at the centre of creation, Indigenous beliefs often perceive a joined community of beings, "living as nature" itself, where animals are kin and teachers. The "honorable harvest" principle, where animals are respected even in hunting, is a key concept.

Jainism emphasiises ahimsa (non-violence) as its paramount principle, extending to all living beings. This commitment informs a strict vegetarian diet and a philosophy of minimizing harm to even the smallest organisms.

Jain practices like jiv-daya (compassionate action) and the operation of animal sanctuaries reflect this core value. Sikhism, also belonging to Indian family of religions, emphasizes compassion (daya) for all creatures, viewing them as manifestations of God. The Guru Granth Sahib contains verses advocating for kindness and recognizing the divine presence in all beings. While some historical Sikh figures engaged in hunting, modern Sikhism generally promotes vegetarianism and condemns cruelty to animals, as reflected in the operation of community kitchens (langars) that serve only vegetarian food.

Thus on the whole the book provides a panoramic view of the values and visions of various religions with regard to non-human animal welfare and also takes a look into the way each society adhering dominantly to a particular religion treats animals. It also explores and exhorts the religious adherents and the leaders as to, how the distance between the religious values advocating the welfare of animals and the actual practice of the adherents, can be reduced.

The book could have included the evolutionary worldview that has actually made many religions recalibrate their religious beliefs towards animal welfare. This is more in resonance in a way with Hinduism and Buddhism. On the whole the book is a treat and provides one with possibilities of various missions in this direction.