Books

Human Cosmos - A Complementary Work to Carl Sagan’s 'Cosmos'

Aravindan Neelakandan

Nov 09, 2020, 06:43 PM | Updated 06:42 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

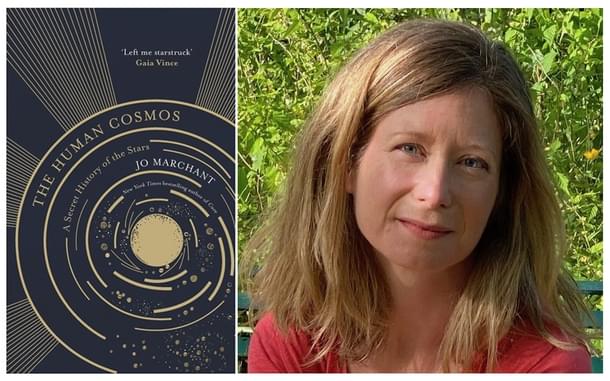

The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars. Jo Marchant. Dutton. 400 pages. Rs 1,962.

In Yogic Psychology there are two ‘nadis’ or energy channels - ida and pingala.

Ida is lunar and pingala is solar. We are a species evolved in a planet that has a sun and a moon. So we have this imagery. Had we evolved in a planet with three suns and two moons what would have been the spiritual imagery that would have evolved here?

The Human Cosmos, a new book by science writer Jo Marchant, explores in detail how twelve important domains, from mythology to mind, which define us as species, have been shaped deeply by the kaleidoscopic celestial dome.

Throughout the book there is a subtle, even nuanced sense of melancholy over the loss of soulful connectivity that humanity felt with the universe at large.

This sense of connectivity, even oneness, has been an integral, invisible force shaping our evolution – our values, our cultures, our minds and of course our sciences.

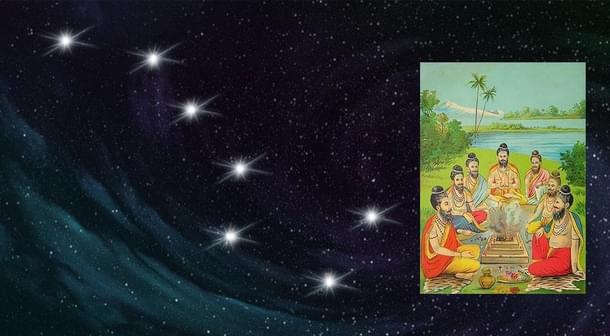

The very first mythological symbol inspired by the stars, cutting across cultures, from ‘holes pierced into the gourd rattle of a Navajo tribe to a painting on a Siberian shaman’s drum. ... even … in the logo of the Japanese car manufacturer Subaru’ (p. 11) is the group of six dots associated with Pleaides.

Indic Alert: In Hindu Puranas, the Pleaides constellation is associated with the six-maidens who nurtured Skanda, the warrior with the spear of Divine Wisdom.

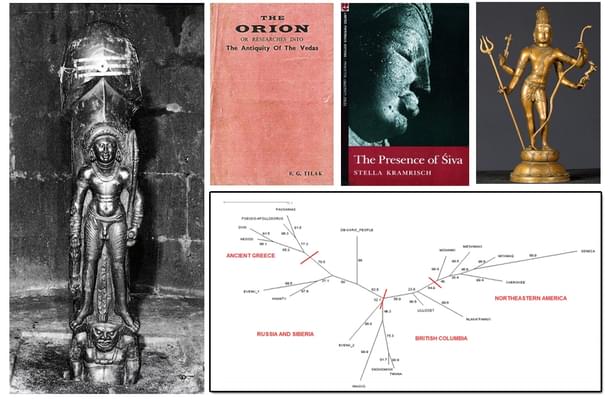

Apart from the much-debated topic of astronomical symbolism in Paleolithic art, she also brings in the novel analysis of the works of the archaeologist and statistician Julien d’Huy who employs the phylogenetic tree method of evolutionary biology to the 93 mythemes or myth-components of 47 versions of the Cosmic Hunter Myth – that of the hunter and the stag, which involves constellations like Ursa Major, Orion, Pleaides etc.

He concludes that the basic myth motif, which has also spread to Amerindians as well, originated in the Steppes and originated 15,000 years ago.

Indic Alert: Despite Vedic literature having the most vivid and the longest continuous vibrant living Hunter-Stag element in Rudra, who is shown shooting the arrow at Prajapati, the Vedic aspect is left out both in the book and in the Julien d’Huy paper.

In this connection one should also read The Orion or the antiquity of the Vedas by Lokmanya Tilak and the related passages in Stella Kramrisch’s The Presence of Shiva.

If we accept Julien d’Huy's thesis of the Hunter-Stag astronomical myth coming from the steppes 15,000 years BP, then the fact that the mature Harappans had these iconographic representations well established in their seals (Ref: Pakistan Archaeology – Iss.10-22, 1986, pp. 149-52) creates some problems for the standard IE-migration theory.

Dr. Marchant goes through various aspects of primordial religion and the strands that continue to this day – shamanism, sacred-herbs-induced altered states of consciousness and how all these are intertwined with the vision of the celestial sky.

The celestial sky unfolded a drama onto which our ancestors mapped their own deep archetypes which in turn got shaped by the rhythms of the cosmos.

Then Marchant narrates how we slowly moved away from the close relations to the cycles of nature.

To her, while the hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic were ‘an integral part of the natural world’, the people of ‘Neolithic revolution … cut those ties and became farmers, controlling and exploiting the land.’ (p.30)

The transition to agriculture creates a shift in the perception of cosmos.

In this context, Göbekli Tepe, the famous temple complex excavated at Turkey is discussed.

To her, it represents the period just before transition to agriculture. She notes two important features: that the human ancestors increasingly replace the animal spirits in the spirit realm; the narrow spaces of the temple structure suggest that they had started creating artificial spaces imitating the caves (pp. 35-36).

If the relation to celestial universe is unproven in Göbekli Tepe, it is the defining feature in the monuments of Neolithic farming communities who built the Stonehenge.

She argues that the 6,000 years of this Neolithic revolution culminated in the following change:

Here the animal spirits are gone; human ancestors rule supreme. And the dependence on caves and the underworld has been broken. People now explored their universe not through individual trance states, deep inside caves ... but in public arenas dramatically aligned with the sky.Marchant, Jo. The Human Cosmos , Canongate Books. Kindle Edition, 2020, (p.41)

Indic Alert: However, a more realistic approach would be that there was emergence and coexistence of the new imageries rather than replacement. For example, in India, with agriculture, the earth-based divinities including serpents became important and their worship became dominant. Worship of plant-based divinities increased and shamanic rituals involving soma became even more entrenched.

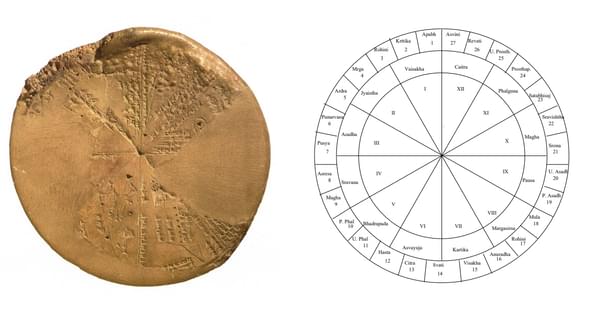

With priests coming up with systematic observations along with the invention of writing, the record keeping of observations also emerged.

There is the fascinating story of Jesuit scholar Johann Strassmaier who initially studied some cuneiform tablets because the Jesuits did not want to miss the debates where they could uphold Bible over the fact of the Biblical flood being a reworked Mesopotamian myth.

Soon, Strassmaier along with Joseph Epping, a Jesuit mathematician whom he got to collaborate with, ended up discovering that the tablets contained rich data on astronomical cycles.

![A cuneiform tablet [left]: A page from the notebook of Johann Strassmaier [right]](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2020-11/c8a57d41-3d6d-48db-abfb-6c425acb7bf6/hc5.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

The Zodiac had been invented by the Mesopotamian priests and soon they had also discovered methods to compute planetary cycles and eclipses.

With Alexander the Babylonian knowledge passed onto Greeks. But while the Babylonian priests included the omens the Greeks were more interested in abstract philosophical ideas being reflected in astronomical calculations. Marchant makes an important observation:

And while the Babylonian belief in omens meant precision mattered above all else, the Greeks had little tradition of accurately observing the sky. They based their models on lofty, philosophical ideals.

While for us today observing omens is superstitious, then it was more empirical and more in tune with the spirit of science than theorising. After all, did not the obsession that theory should be supreme to facts lead to the suppression of irrational numbers and countless other tragedies in the history of science?

She makes another interesting observation with regard to Hipparchus, the ancient Greek astronomer credited with the discovery of precision of equinoxes:

Kugler noticed that the numbers in this theory were identical to those used by Hipparchus. In other words, Hipparchus didn’t derive the numbers in his theories from observations at all. He took them from the astronomers in Babylon.(p.56)

Indic Alert: Prof. Subash Kak’s study of the connection between ancient Indian astronomy and Babylonian is of course another dimension we need to look into.

Marchant points out that the Babylonian astronomy with its techniques enabled horoscope-based astrology in Greek. So, for us Hindus, this explains how horoscope-based astrology itself could have entered with the Indo-Greek interactions in India, and that Vedic astronomy itself was old and had its own interaction with the Babylonian – with perhaps mutual influences.

Astrology was an impetus for astronomy which with scientific revolution became a strong material science. Galileo used to write the horoscopes for his illegitimate daughters (p.59). However, both had to part ways: with astronomy 'making sense of the universe based on objective measurements' and astrology 'emphasising intangible connections and subjective meaning'.

While not an apologist for astrology, Marchant hints at a deeper aspect to this divide – the Cartesian division of the 'mind from body, consciousness from the material world – part of an inexorable shift in the West towards physical causation as the only acceptable type of explanation.'

Then she makes an important observation:

Astronomy and astrology might seem complete opposites, even enemies. But in a way they are twins, reflecting two essential sides of our nature, and born of the same fundamental human desire to see patterns, order and meaning in the sky.(p.60)

With respect to religions, the focus of the book is on the rise of monotheist religions with one extra-cosmic God .

There is a significant observation: the ‘Yahweh-only’ monotheism itself emerged only after the Babylonian sack of Israel, around 550 BCE, that too as a fringe view. It was when the Persians conquered Babylon, they helped Jews rebuild Jerusalem and the sect that resonated with Persian monotheism seemed to have had its ascendancy. Zoroastrianism with its binary view of the universe made its own impact on Judaism.

The later Christian deity, derived from this God, grafted itself with the then very prevalent solar Pagan God – a narrative now well known even to the amateur enthusiasts of the subject.

While Jesus blurred boundaries and identity with the Solar Deity the Mary cult was identifying the mythical virgin mother of God with the moon.

There are other contributions as well – the Egyptian to religious metaphysics; Plato’s concept of soul etc.

And in between comes a very interesting section – how the faithful would join the God in the heavens:

Platonic concepts seeped into Judaism. The idea that the faithful could expect to join God in heaven is hinted at in the Hebrew Bible twice, but only in later books. Ecclesiastes, composed in the Persian period, is unconvinced, asking: ‘Who knows if a man’s spirit rises upward?’ But Daniel, written after the conquests of Alexander the Great, comes down in favour: ‘Those who are wise will shine like the brilliant expanse of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness will be like the stars.’ Centuries later, Islam inherited similar ideas about an eternal afterlife in the sky.(p.78)

Indic Alert: One cannot but think of the possibility of Hindu influence as well. The Vedic Sapta-Rishis to the Puranic Duruva Hindu tradition has a conceptual continuity that could have got into worldview of the writers of the Bible.

As Marchant shows further how Christian theology, as it progressed more and more into philosophically rigorous monotheism, severed the sacredness of the Universe. She brings it all out forcefully thus:

The significance of the switch to monotheism, then, goes beyond the reduction from many gods to one. It’s really a transformation in the kind of universe in which we live. The fifth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo cemented the mainstream Christian view. He had huge respect for Plato: ... But he dismissed the idea of a cosmos infused with God’s soul. … I’m not sure that Constantine himself would have seen it that way. But his conversion marks the moment, for western civilisation at least, when humanity rejected the cosmos as a divine, living being, as all that there was. Instead, it became merely the product of a separate creator. … Our religious beliefs remain steeped with the influences of the sun, moon and stars. But one more tie with the cosmos was cut.(pp.80-1)

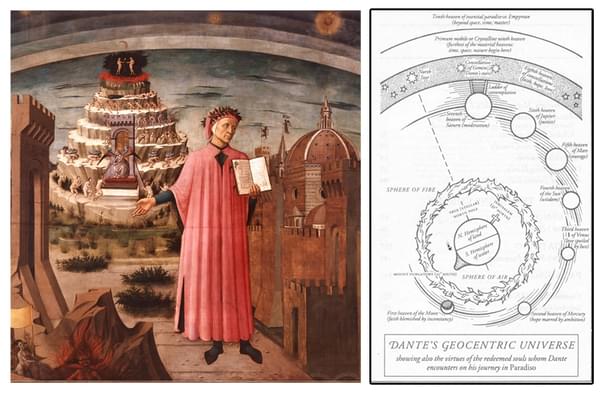

The concept of time as it evolves through the European enlightenment era, makes clock building an important civilisational feature.

Here, Christianity plays its part with the monasteries requiring strict time keeping for the regular practices of the monks. With the God placed outside the Universe and the Universe merely his product and the mechanical view of the universe gaining ascendancy in science, it is not long before the universe itself gets to be seen as a clock.

And it is a poetic mind that first captures and expresses this vision – Dante! In his Paradiso, written in the 14th century, describing his journey through the spheres when reaching the sphere of sun, he ‘compares it to a monastic clock striking the hour for morning prayer.’

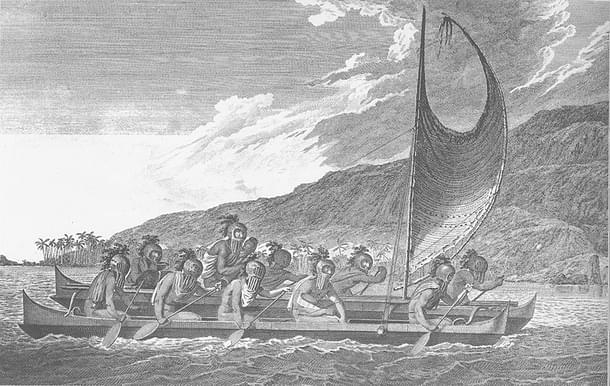

In the oceans, as we humans started navigating, the stars were the guides.

Here, Marchant writes in detail about ancient Polynesian voyages. Voyages of the ancient Polynesians have been subjected to considerable debates.

Today, the ancient, unimaginably long-distance voyages of the Polynesians are almost an accepted fact.

How did they accomplish this without astronomical instruments of navigation?

She says that the Polynesian navigators got trained right from childhood through the creation of ‘complex memory maps using chants, stories and dances, mixed with visual metaphors … as well as religious beliefs’ (p.117).

One important aspect, of their cosmology, is that at the dawn of creation the stars sailed in their canoes to all corners of the sky.

With the Cosmos exorcised of all this sacredness, it becomes a machine created by God and hence also arises the science of Cartesian coordinates:

This Cartesian view, in which we move between fixed, objective points, underlies modern science and has led to breathtaking technological advances. The charts and instruments used by European explorers allowed their ships to conquer the Earth. ... With GPS information now routinely beamed to cars and phones, we can find our location without even looking out of the window, let alone up at the sky.(p.121)

But for this we pay a price:

A team led by the British neuroscientist Hugo Spiers found in 2017 that areas of the brain normally involved in navigation just don’t engage when people use GPS. ... Other studies have shown that people who regularly use GPS become less able to find their way without it, a phenomenon thought to be caused by structural changes in the brain as underused regions start to shrink.(pp.121-2)

Then she simply points out how Polynesians could navigate millions of square miles without technology but with the help of their sacred song and cosmological myths and senses and instincts.

Indic Alert: Vedic imagery saw the terrestrial and celestial oceans as mirroring each other – the two thighs of Varuna with the stars being the sacred fishes.

Then comes the notion of power – from monarchy to democracy – which has also been influenced by our view of the universe.

Our study of the light through the instruments – light from the sun as well as the stars – have opened up hitherto unknown secrets of the universe and nature. She points out:

Our dominant source of knowledge about the universe – what it is; how it was made; how it relates to life, and to us – is now our instruments, not our eyes.(p.160)

This gets reversed in the field of art. Fascinating is the account of how the new physics influenced the cubism movement. Physicist JJ Thompson’s concept of ether influenced the art of Umberto Boccioni just as mathematician Poincare's concept of fourth dimension influenced Picasso.

Naturally she moves on to Kandinsky and Malevich. She points out how the developments in science – particularly physics impacted the souls of the artists deeply. She points to the statement made by Kandinsky in 1913 following the discovery that atoms were not indivisible:

The collapse of the atom was equated, in my soul, with the collapse of the whole world. Everything became uncertain, precarious and insubstantial. I would not have been surprised had a stone dissolved into thin air before my eyes.(p. 171).

Indic Alert: Both Kandinsky and Malevich had significant Hindu influences among other things.

Marchant does mention in some detail the theosophical influences including that of Annie Beasant. However, the Hindu influence is not discussed much.

Malevich was highly influenced by Swami Vivekananda. In fact, while she does not mention it, the Indian-spirituality inspired Russian art movement Amaravella triggered some of humanity’s loftiest space dreams.

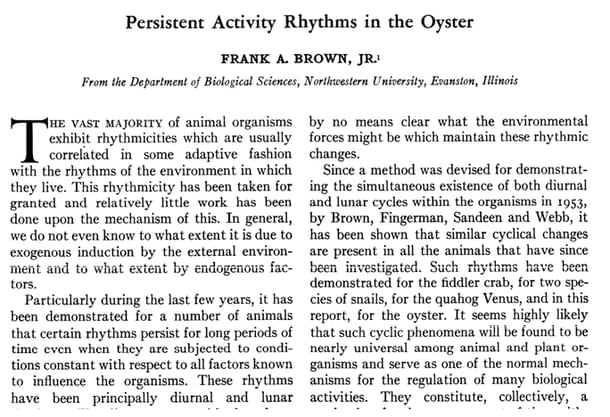

Then the book explores how the very biology of the organism is influenced in ways so subtle by the Cosmos. Sometimes science itself becomes orthodox and shuts out the inconvenient facts.

The example given here is the observations made by biologist Frank Brown in 1954, which suggested the ability of oysters to be sensitive to lunar gravitation.

The scientists strongly disagreed.

The disagreement … reflected a deeper, philosophical split regarding the relationship that living creatures, including humans, have with our planet and the wider cosmos.(p. 185).

The way Brown was subsequently treated in scientific circles, as he was perceived as being a rival to the fast emerging field of circadian rhythms study, is a sad commentary on the way the establishment science functions:

Brown and his cosmic cues were cast out, and the study of biological rhythms became the study of circadian clocks.(p. 190).

Chronobiology made rapid progress. After detailing this progress, Marchant marshals quite a lot of facts from recent studies that show the influence of moon on various phenomena from eco-systems to possible molecular processes in organisms.

She returns to Brown’s research.

What Brown suggested as a possible mechanism to explain his observations was a ripple effect due to the gravity of the moon on the magnetic field of earth.

This should have sounded even more atrocious back then.

Jürgen Aschoff, the physiologist, one of the co-discoverers of circadian rhythm in humans who considered Brown his rival, had devised an experiment along with physicist Rutger Wever in which the human subjects were put in a bunker shielded from all disturbances and showed that their sleep-wake pattern followed a 24 hour cycle.

But there were actually two bunkers reveals Marchant.

One was insulated from electromagnetic interferences as well. Only the subjects in that bunker had 24 hours cycle while electro-magnetically non-insulated bunker subjects followed a cycle of 24.8 hours. Wever published these results.

Despite the heavy criticisms and humiliation from his colleagues Brown stood his ground and his vision was rooted in a view of the universe that was non-dual.

The universe is one,’ Brown wrote in 1977, a few years before he died. ‘Cosmobiology is a field which must and will be explored.’ It’s the kind of comment that saw him sidelined as a misguided eccentric. . . He didn’t get everything right, but he did, I think, see a fundamental truth about the nature of life and our relationship to the cosmos, the consequences of which we’re only just beginning to grasp.(p. 206)

Indic Alert: Marchant points out the relationship between lunar and fertility cycles which had been observed and recorded by Paleolithic artists. And also points to the continuity of the notion prevalent in all cultures of the relation between the moon and the biological phenomena on the earth. Yet it is in Bhagavat Gita that a connectivity between all-pervading Consciousness and this relation has been probably the most clearly stated [BG 15:13].

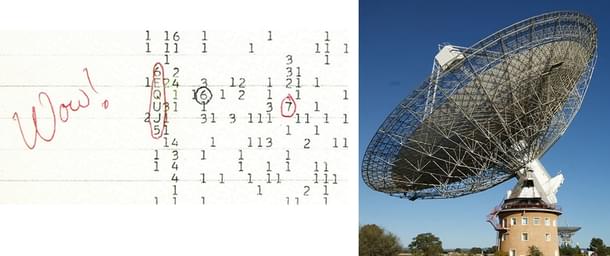

What about life and intelligence in other planets? There have been many false alarms – from the wrongly identified Martian canals to the ‘WoW’ signal to attributing PULSAR signals to ‘little green men’ to Oumuamua the first observed interstellar object passing through our solar system.

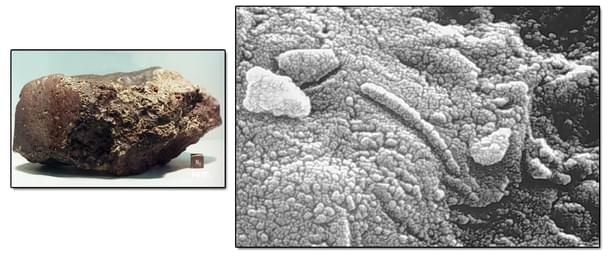

Here, the case of a ALH84001, a fragment of a Martian meteorite which became sensational with claims and counter claims of the possibility of a fossilised proof of microbial activity in it – was a strong suggestion of life on Mars.

Today, with the resurfacing of a possible proof of life on Venus, a planet once ruled out as hostile for life, this chapter makes an interesting read.

As through inter-disciplinary studies, we search for the possibilities of life and intelligence elsewhere in the universe, the quest also makes us redefine our concepts of life and forms of mind. She says:

… scientific results are now nudging towards the possibility of not just other life in the cosmos, but other minds. Scientists are starting to consider the idea … that consciousness, experience, is not a one-off by-product of chemical evolution but a fundamental feature of the universe.(p. 229)

Indic Alert: Among the world religions the Hindu family of religions, Vedic, Buddhist and Jain in particular, have conceptualised various realms and planets.

One of the most popular epithets for the Goddess used all over India is ‘Aneha Kodi Brahmanda Janani’, She who gives birth to infinite number of universes.

While Arthur C Clark considered discovery of an alien intelligence a ticking time bomb for the geo-centric exclusive monotheisms and Carl Sagan brought out the conflict that such a religion might face in his novel ‘Contact’, the Hindu religions have embraced the possibility of the universe teeming with lives of all forms and each with their own consciousness – all sacred.

It is with respect to our mind that the book reveals its core argument. We have lost the sense of awe – not wonder but awe.

Dacher Keltner, a psychologist, in an important work identified awe ‘as the feeling we get when confronted with something vast, that transcends our normal frame of reference and that we struggle to understand’ (p. 233).

Studies have shown that those subjected to the feeling of awe are more ethical and empathetic. They had a vanishing notion of ego-self

‘Awe produces a vanishing self,’ Keltner told me. ‘The voice in your head, self-interest, self-confidence, disappears.’ As a consequence we feel more connected to a greater whole: society, Earth, even the universe.(p. 235)

She also brings in William James and the variety of expansive experiences of consciousness he had collected not only from religious practitioners but also poets etc. She also mentions the sudden mystic experience that Canadian psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke had when he ‘saw that the universe is not composed of dead matter, but is on the contrary, a living Presence’ (p. 237).

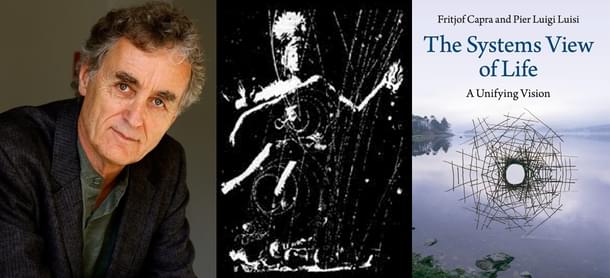

Indic Alert: The a very similar but even more vivid and transformative experience happened to physicist author Fritjof Capra while he was in a beach:

… until that moment I had only experienced it through graphs, diagrams and mathematical theories. As I sat on that beach my former experiences came to life; I ‘saw’ cascades of energy coming down from outer space, in which particles were created and destroyed in rhythmic pulses; I ‘saw’ the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy; I felt its rhythm and I ‘heard’ its sound, and at that moment I knew that this was the Dance of Shiva, the Lord of Dancers worshipped by the Hindus.Tao of Physics; Preface [December 1974]

In fact, Capra was inspired not only to write Tao of Physics which became a classic for the seekers since it was written but also went on to write a series of books which developed a worldview encompassing biology, psychology, health, economics and ecology.

Today his courses on deep ecology and sustainable development are a milestone phenomenon.

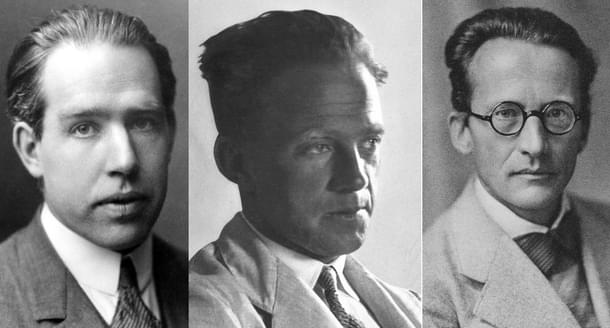

Writing on the emerging vision of reality from the implications of Quantum Mechanics, Marchant quotes Erwin Schrodinger:

Erwin Schrödinger argued that ‘the material universe and consciousness are made out of the same stuff’, and suggested that science needed ‘a bit of blood transfusion from Eastern thought.’(p. 243)

Indic alert: It is well known today the love Schrodinger had for the Upanishadic Vedanta.

In his What is Life- a work that actually triggered the chain of events leading to the discovery of the DNA he quoted the Mahavakya – Tat Tvam Asi.

More importantly, the unity in duality – a substance that conserves itself through generations at the same time producing diversity- could be conceived by him at least partly because of the very similar Vedantic view of life.

Dr. Marchant also points out that the reductionist view that is materialistic, atomistic and highly impersonal is also highly successful:

Don’t be misled by our passions and poetry: humans are ‘robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes’ (Richard Dawkins); ‘nothing but a pack of neurons’ (Francis Crick); ‘just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet’ (Stephen Hawking). It’s a view that’s not great for our pride, perhaps, but has been undeniably successful in terms of predicting and manipulating the physical world.(p. 245)

Nevertheless, there is an alternative emerging from some of the best minds of science to this highly reductionist view of us and our place in the universe. She cites among others string theorist Brian Greene's book Until the End of Time (2020).

Indic Alert: In this book, Brian Greene mentions about Hinduism. He is very careful with respect to what he considers as the Hindu-Buddhist seeking of a reality beyond the illusions of everyday perception, a characterization that also describes many of the most surprising scientific advances of the last hundred years'.

To him it is 'never ... more than a metaphorical resonace between distinct ideas vaguely constructed.'

Two things he mentions here are important for Hindu readers here. One is his conversation with Dalai Lama where the venerable Lama differentiates between science of the matter and science of consciousness - a Dharmic equivalent of Stephen Jay Gould's Non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA).

![[left] Indian rationalists expose blind-folded reading for what it is - simple magic trick anyone can perform.[right] Blind-folded reading is a staple diet of many new age cults like the Bronokoff method, Ramtha school of enlightenment. ](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2020-11/8fabf115-8b8b-4eef-9f76-4697326edc70/hc10.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

The other is his encounter with the Ramtha school of enlightenment which was promoting feats like blindfolded reading, blindfolded archery etc.

Whether it is the fake Lemurian incarnation Ramtha or the alien from hollow earth resurfacing in a particular Guru, often quantum mechanics gets abused for their silly parlour tricks passed on as psychic powers. Healthy skepticism protects us from such pitfalls.

Today in the field of philosophy also concepts like panpsychism are beginning to emerge in fresh ways. She cites Freya Mathews, ‘a cosmopsychist philosopher of nature’ who uses the metaphor of a great ocean coursed by currents and waves.

In this view, our minds are like intricate whirlpools or vortices within that ocean: a continuous part of the overall field, yet also with a discrete, inner experience that’s inaccessible from outside.(p. 248).

Indic Alert: An Indian mind would have now naturally gravitated towards Adi Shankaracharya and later Sri Ramanuja using the simile of of the ocean and the waves. Adi Shankara attributes this simile to Bhartrprapanca, a Vedantin before his time and paraphrasing him states that the Brahman is simultaneously dual and one just as the water is real as also its modifications, the waves, the foam, the bubble.

Thus, the multiform is real like the waves but the Brahman is the ocean itself. There are conceptual differences between the panpsychism of Freya Mathews and the Vedantic simile but the similarity is nevertheless striking. ('Shankara and Indian Philosophy', N.V.Isaeva, 1992)

In essence, this book is history of science told in a refreshingly different way. It approaches science from a deep psychological perspective and creates space for all creative human interactions with the cosmos, not just scientific but also artistic and spiritual.

It also shows how they are interrelated and inspire each other. Dr. Marchant has shown a new and fascinating way of looking at the evolution of human creativity in general and science in particular.

That such a book can be written without mentioning India at all is really worrisome. The book is more than sympathetic to the Hindu worldview which it does not mention by name.

It is a brilliant book that transcends narrow boundaries of academia. Yet even as Persia and China are mentioned India is bypassed in the grand narrative the book weaves. One hopes the author will be open-minded enough to rectify this deficiency in this path-breaking book.

I started the review intending to write a conventional 750 to a maximum 1,500 words review. But this book is as important and classic a book as Carl Sagan’s Cosmos and is a healthy complementary book to Cosmos, whether the society including the academia at large recognises this or not. Hence this very detailed review.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.