Books

Swayambodha-Shatrubodha: Why Hindu Survival Demands Clarity About Self And Enemy

Jataayu

Sep 06, 2025, 07:00 AM | Updated 08:32 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

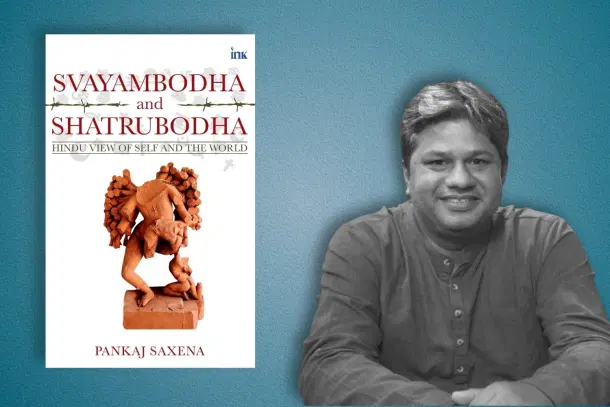

Swayambodha and Shatrubodha: Hindu View of Self and the World. Pankaj Saxena. BluOne Ink. Pages: 608. Price: Rs 500.

Pankaj Saxena's Swayambodha and Shatrubodha is a bold, pathbreaking book that puts its sole focus on a subject of utmost importance for Hindu society in its ongoing civilisational battle.

The book starts with a question that is on the mind of many common people in India, including Kalicharan, the author’s taxi driver. How do Muslims and Christians, despite their numerous differences and internal conflicts, unite both in India and across the world, while Hindus, with similar differences and conflicts, are unable to do so and often find themselves losing to these “minority” religions, failing to resist their aggression?

“It is their deep sense of the enemy, their Shatrubodha,” says the author. All the infighting Islamic groups are clear that non-Muslims are always the enemy, and in their “pyramid of priorities”, even a good and moral non-believer is lower than the worst kind of believer. This is epitomised in the opinion of the Ali brothers about Gandhi: “Yes, according to my religion and creed, I do hold an adulterous and a fallen Mussalman to be better than Mahatma Gandhi,” he points out.

So, “the primary problem of the Hindu society, and of any other pagan polytheistic society, is its lack of Shatrubodha. Hindu unity is a necessary goal. But it is not sufficient. What makes it sufficient is Shatrubodha. We need to know who the ideological enemy is and what it thinks. If we refuse to fight ideological enemies, then we have to fight physical enemies on the streets” (pp. xviii, Introduction).

This is the key theme. The rest of the book is an elaborate multipronged discourse through comparative religion and history, detailed exposition of the problem and advocacy for the solution. This forms the vital three-fourths of the book, Section B.

The remaining one-fourth is the initial part, Section A, Swayambodha or knowing who we are, which is a sub-theme. It is a primer on the fundamentals of Hindu Dharma and its spirituality, as the author sees it. It is written as a backgrounder to drive the point about the need for Hindus to appreciate the common elements of their Dharma amidst the breathtaking diversity that often confounds them, and to recognise the unique features that distinguish their Dharma from the religious ideologies of the enemies.

Those self-conscious and assertive Hindus who are already convinced of this can also read it, as it would enrich their appreciation of their own culture and tradition.

This allocation in the book, of giving more weight to the Shatrubodha portion, is very appropriate. It shows the author’s deep diagnosis of what ails Hindu society and plagues the Hindu psyche, and his correct understanding of the priorities.

“Even while Dharmic sects think in eternal cyclical time and monotheistic religions think in limited linear time, the former have short-term strategies while religions like Islam and Christianity think and plan in long arcs. This is due to the monotheistic aspiration of world conquest and domination. These plans, when executed, become the long arcs of history” (pp. 296).

This insightful analysis gives way to two brilliantly written chapters: The Long Arc of Christianity and The Long Arc of Islam.

How Christianity conquered the Roman Empire in the first few centuries of the Common Era, riding on the tolerance and generosity of the Pagans, opening up conversions to everyone despite being a mutant of the non-converting Jewish religion, penetrating into different sections of society including upper classes, is narrated crisply.

Christianity played the victim card, with the imagery of Christ as the “lamb” while it was in the minority, but increased its numbers stealthily. The striking similarity of this to the situation in present-day India is unmissable.

The antecedents that led to the conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine are valuable lessons in history for Hindus. Its consequences were brutal for Pagans, with the destruction of temples, burning of books, mob lynching of philosophers and scientists like Hypatia, and the total extinction of Roman Paganism.

How Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics “digested” Rationalism to prove Christianity when it faced intellectual crisis during the Dark Ages is explained, followed by the discussion of “Indigenisation” of Christianity in India, showing how strategies are perfected and deployed by the Church over centuries.

“Christianity behaves like a civilisational sniper: waiting patiently at the outskirts of an ancient society for many centuries to strike at the right time” (pp. 330), notes the author.

South Korea, which scarcely had any Christians before 1945 but now has a huge Christian demography and dominance, is a case in point. The extraordinary situation that Korea went through during the Second World War, with Japanese occupation and communist atrocities, was exploited by Christianity to the hilt, leading to the near-total extinction of the Korean Sendo tradition.

Korea-like conversions have been happening recently in three Indian states: Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Arunachal Pradesh. The North-East states of Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur are almost fully Christianised, the book records (pp. 324–342).

In Islamic history, we see the recurring pattern that “the Muslim armies never stopped at political and economic victory until religious victory was achieved through forced conversions of the defeated societies” (pp. 346).

Those converted became part of Islam and started attacking others with equal or greater zeal. Once a Muslim majority is achieved in a country or region, the remaining non-Muslims are eliminated through genocides and ethnic cleansing, as happened with Hindus in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Kashmir in recent times.

Coupled with the religious command that “anyone who leaves Islam would be put to death”, this had serious implications for the world. “While the opponents of Islam need to keep winning repeatedly and endlessly until Islam is gone, Islam only needs to win once” (pp. 348), points out the book.

Even humiliating defeats of Islamic armies did not cause long-term damage to Islam, except for a minor dent, because the victors never converted Muslims to their religions, the book notes.

In the case of the Mongol victory over the Abbasid Caliphs of Baghdad in the 13th century CE, after three generations of Buddhist Mongol Kings who gave total freedom to their majority Muslim subjects, the fourth, Ghazan, was forced to convert to Islam to prevent a rebellion and Islam finally triumphed (pp. 349–352).

The fall of Constantinople at the hands of the Ottoman Muslims, after persistent Islamic war efforts spanning over 900 years, is another example.

How multicultural Lebanon, with a 54 per cent Christian and 44 per cent Muslim population in the 1950s, was turned into a Muslim-majority state within three decades through demographic explosion and Jihadi terrorism from nearby Palestine and Syria is a depressing story (pp. 366–370).

The large-scale genocide of Armenian Christians at the hands of the Turkish Islamic state and society is another heart-rending tale (pp. 371–376).

“Viewing Muslims as local minorities is not only dangerous for the future of any country, but downright suicidal. Radical Islam must be seen as an aggressive global majority. It uses democracy as an opportunity to capture important institutions and then to grab power and destroy the very same democracy” (pp. 367), cautions the author.

The succeeding chapter, Weaponisation of Life, explains how Islam and Christianity make every aspect of life a dimension of their war against “accursed idolators”: government, charity, healthcare, education, relationships and even death.

The theological impulse that motivates and guides these two religions in their acts of destruction is the concept of Prophetic Monotheism, with Christianity and Islam being two different expressions of the same concept.

This is dealt with in detail in the preceding Chapter 6. The idea of “One True God”, the “Surrogate Spirituality” through his Prophet, “One Life” metaphysics, Heaven and Hell, and “Judgement Day” in contrast to the doctrine of rebirth in Dharmic traditions, dividing the world into People of the Book versus others, and Iconoclasm are all covered.

Chapter 7 presents the Hindu critique of this concept, first through the framework of Pancha Rnas (Dharmic obligations towards gods, ancestors, Rishis, fellow humans and all living beings) and then through the writings of Ram Swarup based on Yogic states of consciousness.

Under the chapter Hindu View of Secular Modernity, the book gives a detailed account of how the idea of Secularism had its origin in medieval Christianity as a response to Protestant reform movements aimed at separating the powers of Church and State, and how it was thrust upon India which did not have that historical context.

The internal contradictions and faults of Indian Secularism are brought out brilliantly. Quoting Sita Ram Goel, the author asserts:

“The adoption of Secularism by the Indian state was the greatest tragedy that happened to India after Independence. It did not solve any problem, but created many instead. It de-Hinduised the Indian state and Hindu society, gave the status of Dharma to Islam and Christianity and promoted the delusion of sarva-dharma-samabhava. At the same time, it facilitated the successive radicalisation of Christians and Muslims in India. It functions as a magnet that attracts all breaking India forces” (pp. 410).

“If Sanatana Dharma has to survive in Bharatavarsha, then secularism must go,” he recommends (pp. 438).

The penultimate chapter presents the Swayambodha–Shatrubodha (SS) scale in a concrete, tangible form, aiming to provide practical guidance for Hindus gleaned from all the learnings.

All Hindu sects and communities form the innermost “Swayambodha circle”, and the friendly Dharmic religions like Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and the Pagan traditions of the world form the immediate “Mitrabodha circle”. The hostile monotheistic religions form the outer “Shatrubodha circle”.

“This map is about ideas, ideologies and institutions and not individuals. Christianity is an inveterate enemy of Hindu society, but common Christians can only be viewed with empathy. The same is the case with Islam and Muslims. It is the ideology that exhorts the individual for good or bad acts,” emphasises the author, pre-empting the risk of this being misunderstood as labelling and targeting specific groups of people.

He follows it up with a bold assertion: “All those whose ancestors were Hindus thus have to be welcomed back eventually with Ghar Wapasi” (pp. 452).

The author presents interesting analysis of historical leaders like Gandhi, Ambedkar, Swami Dayananda, Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo, evaluating each of them on both the S scales and assigning scores.

The same exercise is repeated for a spectrum of Hindu movements starting with the Sangh Parivar, shades of “right wing” and also the fringes like the “neo-trad” groups on social media. This exercise offers good clarity in internalising the concept and putting it to practical use.

The book ends on an optimistic note, expressing hope in the Hindu Renaissance visible across India and in its ability to fight its civilisational enemies.

Those fighting to preserve ecology are in the same boat as Hindus, the author observes. In a very evocative passage, the author quotes from The Firmament of Time by Loren Eiseley, citing how Eiseley eventually settles into spiritual peace after lamenting the destruction of nature and culture.

Ram Swarup pondering about “theocide”, the destruction of all natural religions, is cited next, followed by his assertion: “Pagan gods are not dead. For, nothing that has any truth in it can be destroyed” (pp. 483–485).

I have been reading Pankaj Saxena over the past few years. I always found his writings rich in content and sharp in focus. This book is no exception.

True to his intellectual lineage in the Ram Swarup–Sita Ram Goel School of Hindutva, Pankaj presents his arguments and conclusions in a compelling manner, without mincing words, incorporating the combined strength of the entire discourse created by this school, including other great authors of the Voice of India publications.

His strong spiritual anchoring is evident from the dedication of this book to his spiritual Guru and the reverential references.

The seven-page Acknowledgements section at the end is very nice. It reads more like a brief “intellectual autobiography” than the usual recounting of names.

I particularly liked the part in which Pankaj says, “it was in the lanes of literature that I found pathways to the world,” and expresses gratitude to the literary masters he read, the likes of Premchand, Tolstoy, Dickens and Wade Davis, calling them his ancestors, the “literary Pitras” (pp. 494).

I think this distinguishes him as a quintessential writer amidst the many authors from different professional backgrounds writing books on Hindu society, its problems and the civilisational battle in recent years.

His prose is absorbing and eminently readable because of this, which gives a refreshing feel and adds great literary value to the Hindu discourse at large.

That is one of the many strong reasons for him to continue writing and enlightening us with more books.

Note: This review was originally published by the author on his blog.