Books

Trojan Narratives: What They Are And Why You Should Be Careful

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 01, 2024, 01:56 PM | Updated Dec 06, 2024, 06:12 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A new non-fiction work captures public attention, exploring the life of an icon or a compelling social phenomenon. Meticulously researched, it unveils hidden dimensions, enriching our understanding of a leader or a pivotal civil rights campaign.

Even those well-versed in the subject matter find themselves surprised and enlightened, their preconceptions challenged as the narrative reshapes the historical and contextual landscape.

Yet, even within such meticulously refreshing work, may lurk a trojan narrative, subtly woven into the main discourse of the text. Subliminal it bypasses the reader's conscious awareness, embedding itself deep within their psyche.

The trojan narrative operates with 'suppressio veri, suggestio falsi'—suppressing truth while suggesting falsehood—to advance a specific socio-political agenda, to reinforce a stereotype or further an ideological vested interest.

Here we shall see such shadow narratives in otherwise excellent works.

The first one is, Swadeshi Steam: V.O. Chidambaram Pillai and the Battle against the British Maritime Empire, written by A.R. Venkatachalapathy, a historian and a Professor at Madras Institute of Development.

The book is excellent and perhaps the most thorough work on V.O.Chidambaram Pillai (VOC) as on date.

When he describes Tuticorin, the ground zero of VOC's activism, and the places around, he explains the hotels in the town. He writes:

Less than 2 km from the railway station, in Melur, there were three hotels, all run by Brahmins. As eating-houses run by Brahmins, while all castes could partake of the food, these establishments had a reserved section for Brahmins where others could not set their eyes on the food and thus ‘pollute’ it. A choultry (a free traveller’s inn), also for Brahmins, provided free meals and provisions to the more orthodox who preferred to cook their own meals.(p. 56)

One should note the casual dropping of the term that Brahmins considered their food getting polluted by the eyes of others. This could have been written in many other ways. It could have just been said that the Brahmins had strict observances of ritual purity with respect to food and hence they took their food separately. But the author choses a portrayal that maximises negativity towards Brahmins here.

In 1907, VOC met his political guru Tilak. Tilak had been conventionally portrayed as a social conservative who was opposed to reforms. That picture has been reinforced by various stands he took which could at best shown him as a very hesitant person with respect to reforms.

However, VOC, a non-Brahmin from southern India, had provided refreshing data that though would not completely negate the conventional conservatory image of Tilak, definitely challenged it.

This is an important datum for any researcher of social history. VOC writes:

[O]ur noon meal was waiting for us for a very long time as my Guru was not able to leave the crowds that were coming by thousands to kiss his feet. At about 3 p.m., one of our Surat friend asked the crowds to wait for a few minutes and took my Guru, Babu Arabindo, myself and a few others to a back room to have our meals. Having known that we belonged to different castes and creeds and thinking that my Guru might not like to sit and take his food with us, that Surat friend asked my Guru ‘May I arrange to serve you the meal in the next room?’ My Guru promptly replied ‘All patriots are of one and the same caste and creed’ and sat amidst us and took his food with us. That is his so-called Orthodoxy!V.O. Chidambaram Pillai, Reminiscences and Anecdotes of Lokmanya Tilak, Vol. III (Kesari Press, 1928), 160.

It is striking that the historian, meticulous in documenting the segregationist practices of Tuticorin's Brahmins, omits a significant detail: Tilak, despite his conservative image, defied caste norms by dining with fellow patriots.

This selective reporting, especially when juxtaposed with the previous portrayal of Brahmin orthodoxy, creates the trojan narrative here.

While a comprehensive account might be impractical given the focus and subject matter of the book, acknowledging Tilak's patriotic caste transgression would have provided a more balanced perspective.

In 1907, VOC witnessed Tilak declare and demonstrate all patriots as one, transcending caste and creed.

What VOC would not have known was that that Tilak, four months before his death, had written in Kesari (16 March 1920) that ‘anyone who spent his life in Indian freedom struggle must be treated as a brahmana to whatever caste or sub-caste he might have belonged by birth, that caste should not be treated as a matter of birth but … as dependent on qualities and actions’.

Tilak had quoted a Pali verse from Suttanipata to fortify his argument. That this statement was not mere words but had arisen out of his own life’s deeds is a testament to Tilak’s consistent commitment to social reforms in his personal life, whatever his confusing and shifting stands in the public.

Venkatachalapathy's meticulous research remains unimpeachable, yet a curious omission casts a shadow.

While diligently documenting the segregationist practices of Brahmins, even going an extra step to give its religious reason, he overlooks VOC's first-hand account of his Guru-figure Tilak defying caste norms.

This selective reporting, especially when contrasted with the earlier depiction of Brahmin orthodoxy, hints at perhaps an unintentional 'trojan narrative.' Despite this, the book's overall excellence remains undiminished.

II

The next book in question is a book by author Manoj Mitta: Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India (Westland, 2023). The title itself has a micro-trojan hidden in it because the battles for equality mostly mentioned in the book were fought in British India, not ‘Hindu India’.

The author discusses the support and opposition to a bill termed the ‘Hindu Marriages (Validity) Bill’ introduced by Vithalbhai Patel (1873-1933), a freedom fighter and elder brother of the famous ‘Sardar’ Vallababhai Patel.

The bill legalised all inter-caste marriages between all Hindu castes including Scheduled Communities and Scheduled Tribes. Many influential leaders of the Arya Samaj strongly supported the bill. Lala Lajpat Rai supported it too, while both Tilak and Gandhi were against it. When Mitta analyses the supporters he singles out Sri Aurobindo. He writes:

Aurobindo Ghose’s support was, however, a qualified one: ‘I should have preferred a change from within the society rather than one brought about by legislation.’ At the same time, ‘it would appear’, he said, that ‘the difficulty created by the imposition of the rigid and mechanical notions of European jurisprudence on the old Hindu Law’ could only be ‘removed by a resort to legislation’.

In reality, Sri Aurobindo’s support for the bill was complete. It took into account the historical context of colonialism and its impact that made the Hindu scriptures lose their dynamic nature and made them stagnate into the tyranny of a mechanical textual literalism.

The context of Sri Aurobindo’s response itself was quite interesting.

Vithalbhai Patel was part of the administrative circle of a newspaper called The Hindustan, which was run by a staunch Arya Samajist Sheth Ranchoddas Lotewalla, who was quite a radical social reformer. When Vithalbhai Patel introduced the bill, he wrote to Sri Aurobindo asking for his comment.

During this period, Sri Aurobindo had moved away from politics and was concentrating on his sadhana. Yet he wrote back a detailed response, demonstrating the importance he attached to this issue.

With his characteristic insight, Maharishi Aurobindo recognized how colonial jurisprudence had impacted the interpretation of Hindu scriptures and that the remedy for this particular malaise was very much a legislative one. Here is his complete reply, which is worth quoting in full because of its relevance to Hindu society even today:

In answer to your request for a statement of my opinion on the inter-marriage question, I can only say that everything will have my full approval which helps to liberate and strengthen the life of the individual in the frame of a vigorous society and restore the freedom and energy which India had in her heroic times of greatness and expansion.

Many of our present social forms were shaped, many of our customs originated, in a line of contraction and decline. They had their utility for self-defence and survival within narrow limits, but are a drag upon our progress in the present hour when we are called upon once again to enter upon a free and courageous self-adaptation and expansion. I believe in an aggressive and expanding, not in a narrowly defensive and self-contracting Hinduism. Whether Mr Patel’s Bill is the best way to bring about the object intended is a question on which I can pronounce no decided opinion. I should have preferred a change from within the society rather than one brought about by legislation. But I recognise the difficulty created by the imposition of the rigid and mechanical notions of European jurisprudence on the old Hindu Law which was that of a society having and developing by an organic evolution.

It is no longer easy, or perhaps in this case, possible to develop a new custom or revert to an old – for the change proposed amounts to no more than such a revision. It would appear that the difficulty created by the legislature can only be removed by a resort to legislation. In that case, the Bill has my approval.Sri Aurobindo, ‘A letter of Sri Aurobindo’, in Sri Aurobindo: Archives and Research, Vol. 8, No. 2, December 1984, 190

Though Sri Aurobindo would have preferred an internal change, a change within the society, he also recognised a near impossibility of such a change happening.

The over-imposition of European jurisprudence on the old Hindu Law had made such a change impossible. As the difficulty was created by legislature, it could only be removed by a resort to legislation. In such a situation the Bill had his approval. Not partial approval, not a qualified approval.

Mitta, however, omits Sri Aurobindo's acknowledgment of this impediment and his consequent, unqualified endorsement of the bill. This selective presentation distorts Sri Aurobindo's actual stance.

III

Yet another instance of trojan narrative can be found in the same book, where the author describes the temple entry movement.

The context is the temple entry movement along with the efforts to create a legislation to ensure universal temple entry by Chakravarti Rajagopalachariar (Rajaji) and his team.

Rajaji's initial Malabar temple entry legislation was a strategic manoeuvre. He withdrew support for a more progressive universal bill which he himself initially mooted and was proposed by Scheduled Community leader M.C. Rajah.

Rajaji cited implementation challenges and advocated for a multi-dimensional approach. Though perceived as a betrayal by M.C. Rajah and other humanitarians, and rightly so from their persective, Rajaji's actions were guided by a deeper strategy. He envisioned a people's movement to minimise possible violence and isolate those opposing temple entry, reducing them to a fringe group of legal obstructionist obscurantists.

Naturally Rajaji faced brickbats from both the reformers and orthodoxy.

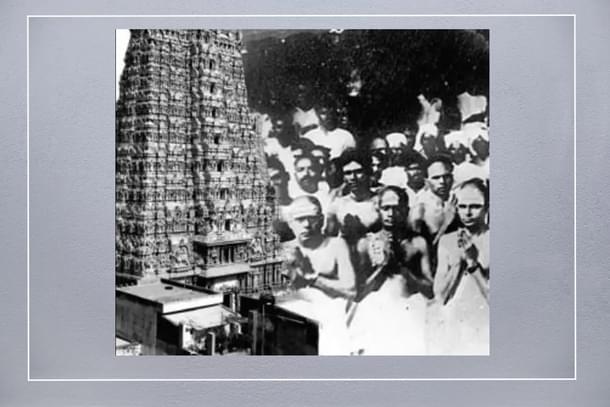

That strategy of Rajaji became the Madurai temple entry movement.

A systematic campaign was launched for the entry of all Hindu communities, including the so-called ‘untouchables’, irrespective of caste differences. From the national Harijan movement, Rameshwari Nehru, was sent to the Madras Presidency to participate in the campaign. In his account of this part of the movement for access to temples, Manoj Mitta gives a subtle twist to the concern of Rajaji. He writes,

[Rameshwari Nerhu’s] first-hand experience in both places helped her see that Rajaji was being more wary than the maharaja had been. Despite giving ‘his wholehearted support to the cause’, Rajaji was ‘very keen’ that temples be thrown open ‘without the aid of law’ and ‘by the voluntary free will of the people’. Her reading was that he desired a situation where trustees, rather than waiting for legislation, brought about temple entry on their own with the assurance that caste Hindus were willing to worship alongside Harijans.Manoj Mitta, p.512

Maharaja mentioned here is the king of Travancore. He proclaimed the famous temple entry for all Hindus in Travancore despite a staunch orthodoxy opposition. So Mitta's passage portrays Rajaji as one who wanted the upper castes to voluntarily allow the 'Harijans' and not totally in favour of any legislative means.

In reality, that was not the case.

Temple entry into Meenakshi temple of Madurai was carefully strategised by Rajaji and his team, to become a holistic victory and infuse fervour into the masses cutting across causes to favour a legislature to open the temples for all Hindus. The entire operation which was spearheaded in the ground by Vaidhyanatha Iyer, and was planned with all contingency plans by Rajaji.

This being the context, what Rameshwari Nehru actually observed and recorded significantly differed from what Mitta had implied in his writing as what Nehru observed.

Her observations challenge Mitta's narrative. Mitta provides a description that implies that ‘despite’ his ‘wholehearted support’, Rajaji expected the trustees to gain entry into the temple. The word ‘despite’ was a clever twist of words generating the trojan narrative. In fact, Rameshwari Nehru’s observations showed admiration for the clear vision and clearer roadmap that CR had facilitated for the temple visit:

The most significant feature of this event was that it was accomplished peacefully without the pressure of law or police or authority. Sri Rajagopalachariar, who gave his whole-hearted support to the cause, was very keen that temples should be opened without the aid of law by the voluntary free will of the people. Consequently a campaign similar to the Travancore one was organised by the Harijan Sevak Sangh. Scores of meetings, which were attended by thousands, were held all over Tamiland. I had the honour of presiding at most of these meetings, where I beheld the joyful spectacle of all sorts of men vying with each other in giving their support.Rameshwari Nehru, Gandhi Is My Star (Acharya Ramlochan Sharan for Pustak Bhandar, 1950), 109

Every movement of the temple entry was carefully planned to avoid or minimise any possible violence. Technically as the legislation had not yet been made, those who entered the temple were actually breaking the then extant law. As soon as the temple entry was accomplished, Rajaji lost no time to bring the legislation.

Those who entered the temple knew that Rajaji was the brain and heart behind the entire movement and its success. A sage, Swami Karunananda, who belonged to the Scheduled Castes community in his pre-sanyas days, entered the temple and was so filled with spiritual feeling that he went into deep meditation. Later, overwhelmed with emotions, he said that Rajaji was indeed an avatar who had come to uplift the downtrodden.

The strategy of Rajaji also outwitted a deeper game by the British. The British sought to exploit orthodox opposition to temple entry, using it both to hinder progress and to justify their continued rule in India under the guise of protecting marginalised communities. Rajaji outmanoeuvred this duplicity, paving the way for social reform and dismantling the British Empire's moral justification.

The most important observation of Rameshwari Nehru was that she saw in the movement ‘the possibility of the Hindu ideals supplying to the world the secret of making democracy effective’.

The title of Mitta’s book without the trojan narrative would have been—Against Caste Pride: Hindu Battles for Equality in British India.

Again the book in itself is a well-written book and it is rich with data which should always sensitise Hindu society and conscience to the kind of hard battles fought for justice in this land. That is why the reader should also be careful with respect to trojan narratives embedded in such important works.