Business

The World Is Running Out Of Chocolate: Can India Help?

Adithi Gurkar

Aug 05, 2025, 02:50 PM | Updated Sep 01, 2025, 03:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In the rolling hills of Karnataka, Ravi walks among trees that may hold the key to saving the world's chocolate supply. The third-generation cacao farmer surveys pods hanging like golden lanterns from branches that have weathered fifty years of monsoons and droughts.

What he does not yet fully grasp is that his family's modest plantation represents something far more significant than a livelihood. It embodies India's unexpected emergence as chocolate's potential saviour.

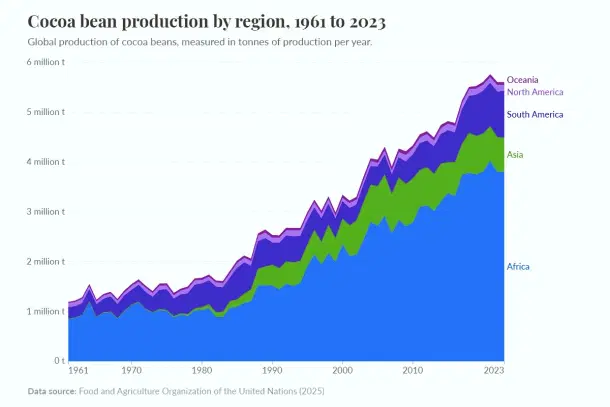

Halfway across the world, the foundations of global chocolate production are crumbling. West Africa, the continent that has supplied 70% of the world's cocoa for decades, faces an unprecedented crisis that threatens to reshape not just the chocolate industry, but the very accessibility of one of humanity's most beloved treats.

Yet beneath this heartwarming tableau lies a graver, bloodier reality.

The Chocolate Emergency

The numbers tell a story of mounting catastrophe. Global cocoa production declined by 13% in the 2023–24 season to 4.368 million tonnes, while demand remained steady, creating a supply deficit of 494,000 tonnes, the largest shortfall in more than 60 years.

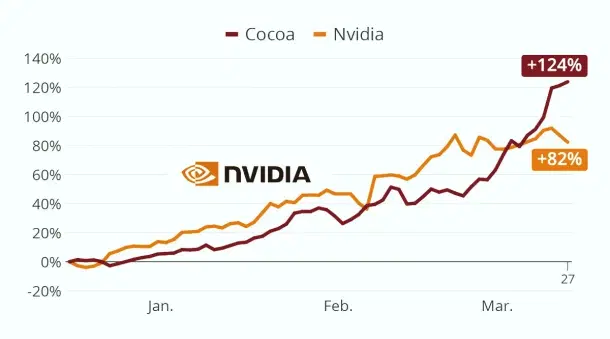

Global cocoa prices have erupted from $2,500 per metric ton to peaks exceeding $12,900 in December 2024, a staggering increase that has sent shockwaves through boardrooms from Hershey to Nestlé. At certain points, cocoa became more valuable per kilogram than precious metals, with price increases temporarily exceeding even NVIDIA's remarkable stock performance.

Behind these stark statistics lies a persistent question the world has struggled with for over two decades: can the planet maintain chocolate production while climate change devastates traditional growing regions?

The production collapse was most severe in the world's two largest producers. Ghana's cocoa production plummeted to only 531,000 tons in the 2023–24 season, down from its usual average of around 800,000 tons, marking the worst-performing session in 15 years. Ivory Coast's production fell by approximately 20% to about 1.8 million tons, significantly below its historical average of 2.25 million tons annually.

Combined, these two nations, which together produce 60% of global cocoa, lost more cocoa output than the entire global shortage. The crisis has been compounded by the cocoa-to-stocks ratio falling to dangerous levels, suggesting global reserves of less than two months of consumption when markets typically require a three-to-four-month buffer for price stability.

What makes these losses particularly haunting is not their rarity, but their inevitability within our current global agricultural system. Despite decades of well-intentioned development programmes and agricultural investments, West African cocoa regions now face escalating friction with a changing climate.

The time has come for an uncomfortable truth. Are our current approaches to chocolate production truly sustainable, or has our reluctance to consider alternative growing regions trapped us in an unsustainable cycle requiring urgent re-evaluation?

The Climate Catastrophe Behind the Crisis

Across the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon — the quartet of nations that have long dominated global cocoa production — temperatures now regularly soar to 41°C, far beyond the comfortable range that cocoa trees require.

Ageing plantations, some with trees over half a century old, struggle against diseases that thrive in the increasingly erratic weather patterns. Rainfall has become a gamble, arriving too late or too early, leaving farmers helpless as their livelihoods wither under unforgiving skies.

Cacao trees demand very specific temperature conditions to thrive, with maximum annual averages not exceeding 30–32°C and minimums staying above 18–21°C. This narrow tolerance makes them extremely vulnerable to even small temperature increases.

Climate projections suggest West Africa will experience 40 additional days annually with temperatures exceeding 32°C, severely impacting harvest quantity and quality.

The 2023–24 season proved particularly devastating due to the El Niño weather phenomenon. West Africa swung violently between extreme rainfall and severe drought. December 2023 saw precipitation more than double the 30-year average, followed by rain scarcity in 2024. This volatility has made cocoa production increasingly unstable.

Professor Minimol J.S. of Kerala Agriculture University tells Swarajya, "Climate change has also accelerated the spread of devastating plant diseases. Black Pod Disease, emerging from humidity created by excessive rain followed by heat, can destroy up to 80% of farmers' crops. Cacao Swollen Shoot Virus Disease affects approximately 20% of Ivory Coast's cocoa and accounts for 15–50% of harvest losses in Ghana."

Beyond climate impacts, illegal gold mining called galamsey in Ghana has become a major threat, with farmers leasing cocoa farms to miners for quick cash, permanently destroying the land.

The economic desperation driving such decisions reflects deeper structural problems in cocoa farming. Many cocoa trees are ageing past their productive years, but farmers lack resources to replant. Despite record-high cocoa prices, government price controls mean farmers still receive low payments, providing little incentive to reinvest.

The human toll mirrors the agricultural devastation. Millions of farmers who have known no other trade watch their inheritance turn to dust. Processing facilities stand idle. Export terminals that once hummed with activity now echo with the hollow sound of economic collapse.

Yet in this global crisis lies an extraordinary opportunity — one that India, traditionally an importer of 70% of its cocoa needs, is uniquely positioned to seize.

India's Unexpected Awakening

The transformation did not happen overnight. For decades, Indian farmers like Ravi have quietly cultivated cacao in the shadows of more prominent crops, their efforts barely registering on global commodity exchanges. But as West Africa's production falters, India's cacao cultivation area expands with the urgency of a nation that has spotted opportunity in crisis.

The economic signals have been impossible to ignore. In Indian markets, cocoa prices have surged from ₹25 per kilogram to ₹1,000, a staggering 4,000% increase that has converted sceptical farmers into enthusiastic adopters almost overnight.

While prices have since stabilised to around ₹550 per kilogram by September 2024, this still represents a threefold increase from previous years, ensuring continued farmer interest. What was once considered a niche crop suitable only for specialty farms has suddenly become one of agriculture's most lucrative pursuits.

The scale of India's transformation becomes clearer in recent production figures. India's cocoa bean production reached 27,600 tonnes in 2024, rising significantly from 19,000 tonnes in 2017, representing a compound annual growth rate of 4.8%.

Andhra Pradesh leads this quiet revolution with 10,903 metric tons of annual production, followed closely by Kerala with 9,647 metric tons. Over 110,000 hectares of land were dedicated to cocoa plantation by 2024, indicating the rapid expansion of cultivation areas.

These may seem modest figures compared to Ivory Coast's traditional dominance, but they represent something more significant: proof of concept for a different model of chocolate production entirely.

India's Secret Recipe

The Climate Advantage That Changes Everything

Where West Africa now suffers, India thrives. The subcontinent's temperatures, ranging from 24°C to 34°C, fall within the optimal range for cacao cultivation, a range that West Africa's changing climate increasingly struggles to maintain. While Ghanaian farmers watch their trees wilt under unprecedented heat, Indian farmers work in conditions that their crops find comfortable.

But temperature alone does not explain India's advantage. The secret lies in an ancient agricultural wisdom that modern monoculture has forgotten: diversity creates resilience.

Professor Minimol J.S. explains the revolutionary approach: "Our multi-cropping system allows cacao to thrive in the shade of coconut and areca nut trees. This isn't just about space efficiency. It's about creating microclimates that protect cacao from temperature extremes while providing farmers with multiple income streams."

This agroforestry model produces results that would seem impossible to West African farmers accustomed to vast monoculture plantations. Indian cacao trees yield between 2.5 to 5 kilograms annually, which is ten to twenty times the global average of 0.25 kilograms per tree.

The implications of such productivity are staggering: India can produce more chocolate with fewer trees, less land, and greater environmental sustainability.

Scientific Innovation at Scale

In research laboratories across Kerala and Karnataka, scientists work with the intensity of those who understand they are racing against time. Kerala Agriculture University, in collaboration with the University of Reed in the UK, has collected over 600 germ-plasm from all over the world to develop heat-resistant cacao varieties, each designed to withstand the climate realities that have devastated traditional growing regions.

"For instance, our cacao hybrids can survive in areas like Andhra Pradesh where the temperature can become relatively high and also in areas of the Northeast such as Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram etc., where the temperature is low. This is thanks to the wide genetic base imparted in the hybrid," Professor Minimol states.

The research extends beyond mere survival. Indian scientists focus on creating varieties that can thrive for 100 years under the multi-crop system, compared to the 25-year lifespan typical of monoculture plantations. This longevity represents not just economic advantage but environmental stewardship on a scale that traditional chocolate production has never achieved.

"We have developed double-crossed hybrids. They are high-yielders with a single bean weighing more than one gram, at par with international standards. These are not merely incremental improvements. They are disease-resistant and drought-tolerant plants emerging from Indian research that can survive temperatures up to 40°C. Conditions that would kill conventional cacao trees. More remarkably, they maintain productivity levels that exceed global averages even under stress conditions," Professor Minimol reveals.

"The highest climatic potential is in Kerala, the quality of the beans is excellent here. However, the main problem is that the availability of land is limited here. Parts of Karnataka and the Godavari belt of Andhra Pradesh are great for cultivation. While land is plenty in Andhra, the issue is that in the summers, the temperature can reach up to 48–50 degrees. However, 99% of Andhra cultivation is from our own hybrid and they are able to withstand the high temperature. There is a slight decrease in the quality of the beans produced during summers due to less fat content," she admits.

She continues, "India also happens to be uniquely positioned when it comes to diseases such as control-swollen shoot disease, which has infected many countries and the Malaysian pod borer. These prevent the export of cacao from such countries. India has no such viral diseases pertaining to the cacao plant."

The Sustainability Revolution

Partha Varanashi, a regenerative farmer at Varanashi Farms, who has become something of a prophet for sustainable cacao production, embodies India's holistic approach. His methods read like a rejection of everything that industrial agriculture has taught the world about efficiency. He advocates for agroforestry and organic approaches for growing cacao.

"When you work with nature instead of against it, the land gives back more than you ever imagined," Varanashi tells Swarajya, walking through his plantation where cacao pods hang alongside coconuts, pepper vines, and medicinal plants. "My trees are healthier, my soil is richer, and my income is more stable than any monoculture farmer could achieve."

Mr Varanashi advocates for cacao to be planted as a fourth-layer crop, growing along with black pepper and banana. "Cacao grows only up to 8-10 feet, does not require direct sunlight, and when grown in multiculture, it can have a really long life, much longer (up to 100 years) than the two-decade survival rate in conventional monoculture systems," he says.

He continues, "When one uses grafted plants, one can expect yields within the third year, while seeded plants provide within the fourth year. Around the sixth to seventh year, one can expect high yield, and around the tenth year the yield stabilises."

While in the 1970s cacao was extensively introduced in large parts of Karnataka and Kerala, thousands of acres of cacao were eventually chopped off to make way for arecanut, which was commercially more viable. However, the trend has reversed, and now the domestic price itself outstrips export prices. At our nursery, where we had 50,000 saplings made, we have almost sold out.

These practices do not just increase yields; they create agricultural systems that become more productive over time rather than depleting the soil. The implications for global chocolate production are profound. India is proving that sustainable agriculture can be more profitable than industrial methods.

The Human Transformation

Farms in Karnataka represent the evolution of Indian cacao farming from simple cultivation to value-added production. They do not just grow cacao but also process it into chocolate, controlling the entire supply chain from tree to bar.

"Training programmes conducted by the Central Plantation Crops Research Institute have taught farmers fermentation techniques that were once trade secrets," Varanashi explains, holding up his Terra chocolate bars that command premium prices in local markets. "Farmers are chocolate makers, entrepreneurs, custodians of flavour profiles that the world is just beginning to discover," he tells us.

This transformation from raw material supplier to finished product creator represents a fundamental shift in how developing nations can participate in global commodity markets. Instead of exporting raw beans at commodity prices, Indian farmers and entrepreneurs are increasingly capturing the value addition that has traditionally enriched processors in developed countries.

"Indian cacao has become quite popular now, but we still are not there yet when it comes to craft chocolate. The demand for craft chocolate is proportional to the demand for cacao, as craft chocolate has a greater percentage of pure cacao in it. Some notable names include Mason and Co of Auroville, Puducherry, with its bean-to-bar, organic single malt; Mysuru's Naviluna with its terroir-centric approach; Paul and Mike; and Manam in Hyderabad. These premium bars command four to five times the price of normal chocolate bars, which have only 2 per cent cacao, in contrast to 60 to 80 per cent cacao present in the premium bars," he continues.

"The flavour depends on where it is grown in India. For example, the beans from Kerala and South Karnataka have a fruity, acidic flavour, with a hint of tobacco, whereas the Ooty belt beans are more pH-balanced with light-tasting cacao."

Village-level processing units are emerging across cacao-growing regions, creating local employment while reducing dependence on distant processing facilities. This distributed model offers resilience that centralised systems cannot match. When one region faces challenges, others can compensate.

The Challenges That Remain

Yet India's chocolate revolution faces obstacles that enthusiasm alone cannot overcome. The expansion of cacao cultivation requires massive investments in farmer education, processing infrastructure, and market development. Many traditional farmers remain sceptical of switching from established crops to cacao, despite the economic incentives.

Climate change, the very force that has devastated West African production, threatens Indian agriculture as well. The question is whether India's diversified, research-driven approach can prove more resilient than the monoculture systems that have dominated global chocolate production.

What emerges from India's cacao revolution is more than just an alternative source of chocolate. It is a completely different vision of how agricultural systems can respond to global challenges. The multi-crop approach that allows cacao to thrive alongside coconut and arecanut trees offers a template for climate-resilient agriculture that other regions could adapt.

As chocolate companies worldwide scramble to secure supply chains that seemed unshakeable just a few years ago, India's emergence as a potential major producer offers hope beyond mere market stabilisation. The country's approach demonstrates that sustainable agriculture can be more productive and profitable than industrial methods.

The transformation carries implications that extend far beyond commodity markets. If India can scale its cacao production while maintaining its sustainable practices, it could demonstrate that developing nations need not choose between environmental stewardship and economic development.

For Ravi, walking among the trees his grandfather planted, the global implications may seem abstract. But his quiet work, replicated across thousands of farms throughout southern India, represents something profound: proof that when crisis forces innovation, solutions can emerge from the most unexpected places.

The world may indeed be running out of chocolate as we have known it. But in the hills of Karnataka and Kerala, farmers are quietly growing the seeds of chocolate's future: one tree, one pod, one sustainably produced bar at a time.

In this transformation lies a deeper truth. Sometimes salvation comes not from doubling down on failing systems, but from rediscovering wisdom that industrial agriculture had forgotten. India's chocolate revolution may be just beginning, but it carries the promise of sweetening not just our palates, but our relationship with the land that feeds us.

Adithi Gurkar is a staff writer at Swarajya. She is a lawyer with an interest in the intersection of law, politics, and public policy.