Commentary

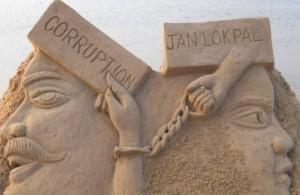

Baba Ramdev, Lokpal and Corruption

Dilip Rao

Jun 08, 2011, 04:31 AM | Updated Apr 29, 2016, 03:02 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

With the dispersal of the crowds from Ramlila grounds, the Baba Ramdev movement might have at least temporarily come to a halt. With a boycott of the Lokpal committee meeting and another fast by Anna Hazare looming on the horizon, the soi disant “civil society” drama shows no sign of abating at the moment. Many have blamed the UPA-2 government for this predicament and there is no doubt it must bear the lion’s share of responsibility for the unfolding chaos; having undermined institutions through financial improprieties, attempting to hand over governmental prerogatives to loud-mouthed nobodies was hardly going to make things better. Once the process unfolded, the Pandora’s Box of claims could no longer be easily shut. With each concession followed by another cringe-worthy surrender, government opponents could scarcely be blamed for anticipating that the establishment would fold yet again like a cheap suit in front of all the cameras and the world. The shock and outrage vented in the aftermath of the police action is a manifestation of this not-entirely-unrealistic expectation failing to materialize.

With more antics awaited, it is about time to give some thought as to what this means for the future of the state and the constitutional order in this country. The Indian Express has editorialized today that the answer lies in calling an immediate session of parliament. This would be a worthwhile effort only if all parties have realized the danger of carrying out politics on the street rather than in parliament. So far, there is absolutely no evidence of such introspection. The Congress party has said nothing about abolishing the NAC or at the very least the Lokpal committee (which seems to be going nowhere at the moment and has been marked by continuing mutual suspicion and repeated outbursts by its “civil society” members reflecting bad faith) and its theatrics can be safely assumed to overshadow any parliamentary proceedings if they take place right away.

The BJP, on the other hand, has fared no better or perhaps, even worse. When it had the chance last session to take up the Prime Minister’s suggestion of systemic reform, it chose not to respond. Once the civil society agitation got under way, it sought a place in the drafting committee but has continued to this day to remain silent on what its views on the matter are or whether it has any different line of thinking that merits granting it a place at the high table. Again when the mutual recriminations in the Lokpal committee began, the party did not, as one might expect, try to regain the initiative by demanding a parliamentary session and debate but chose to back another protest fast by an unelected and unaccountable individual with neither adequate knowledge nor governing experience. Once that was ended by force, it has chosen the safest cause to retain its relevance – yet another protest over police brutality without saying how it might have acted differently under the circumstances. The party has only now sought a session of parliament but it is not clear if it will actually utilize such an opportunity to put forward constructive views to improve the system. All of this does not suggest any sign of realization of how extra-constitutional groups are gaining a growing following which, if present trends continue, will eventually undermine all elected governments irrespective of party affiliation. To add to the confusion, the Supreme Court has now inserted itself into the controversy and with the benefit of the bully pulpit may well come to command the opposition space and dictate the course of events in the days to come. I am therefore not very optimistic that a parliamentary session will necessarily be productive – we may once again end up with a blame game, faux outrage and theatrics with zero tangible gains for the tax paying public at the end of the day.

While parliament may or may not have anything to contribute, passage of a Lokpal bill in some form with or without debate seems likely. While I believe reform is necessary, I have grave reservations about what is being proposed now. I put forward my thoughts here which will hopefully initiate a debate on some of the less discussed aspects of this issue

Tackling Corruption:

There are two overlapping questions here – corruption and the future of parliamentary democracy. Given how the credibility of democracy itself has been put at stake on the former question, it is imperative to deal with it with some urgency. I am going to take up the second question at a later point in order to avoid making this post any longer than it already is.

“Civil society” folks contend that the high cost of contesting an election, the difficulty of raising money without being forced to make illegal favors and the near impossibility of getting a ticket to a winnable seat without being able to spend large amounts virtually puts the prospect of electoral success beyond the reach of a common man. Once spent, the need to obtain a return on that investment virtually guarantees illegal or otherwise illegitimate transactions. Legislatures are therefore not representative of the common man but of those interests with the means and willingness to spend a fortune only to then abuse the authority so obtained to recover their investment together with a profit. Corruption and electoral politics are thus inextricably linked and one is the Siamese twin of the other. The circulus vitiosus can only be broken by do-gooders of “high moral integrity” who can monitor and act against them as all-powerful ombudsmen.

Opponents have contended among other things that democracy notwithstanding all its faults is still the only way to determine the people’s consent and electoral reform rather than anti-corruption measures are the key to solving these issues. The proposed Lokpal authority will be undemocratic and simply end up as one more power center which will soon be overwhelmed by the very same corrupting forces; a lack of accountability will mean locking up this powerful body once formed and then throwing away the key thus giving up any prospect of fixing it if and when the need arises. If unelected officials undermine elected ones, parliamentary authority is so irretrievably weakened that the democracy is reduced to a hollow exercise and will be in peril. Opponents have also been particularly irked by the demand of a bill being drafted by unelected individuals rather than the government as the practice normally is and of “civil society” setting a “deadline” for parliament to pass it.

We are all aware of these arguments, so let us move on to examine the issues more closely. The demand for corruption arises out of electoral expenditure and the supply, i.e. the means by which this cost is met comes from government sources of finance. Lokpal investigations, CAG audits and other investigative bodies all aim at limiting corruption by shutting off the latter part of the equation whereas electoral reforms are an attempt to attack the former aspect. Arvind Kejriwal’s point that they are separate and complimentary and we need both thus makes sense. On the other hand, if we control only the supply side of the equation before dealing with the demand, one of two things could happen. Either the system will find a way to subsume the new arrangement with pliable officials being appointed who will look the other way even as matters continue in much the same way as before or we could wind up with what Nick Robinson pointed out a few weeks ago with respect to Bangladesh – jailing of numerous key and prominent officials on corruption charges. This might generate great press for the moment but is not really a healthy answer as it will undermine the legitimacy of the system not to mention deter other smart and capable individuals from entering public service or gaining political office with society on the whole becoming worse off for it in the long run.

Secondly, opponents both overestimate the impact that electoral reforms can achieve and minimize the potential downsides of the effort. The amounts that have been mentioned in relation to government funding of elections are so minimal that they would come nowhere near to the estimated quantum of expenses currently being incurred even in statewide let alone national elections. Whether the government can indeed afford the huge expenses to fund fully or at least in major part all elections is doubtful; if it does shell out the requisite amount, it is moot whether and how much such an arrangement will end up saving the exchequer relative to what it is losing today. Furthermore, in a country like ours where the dominant discourse is very much to the left of center with differences between parties only a matter of degree, if elections were, hypothetically speaking, fully nationalized and the role of private capital greatly limited, that lack of dependence could very well render ruling politicians becoming entirely obtuse to the interests of free enterprise. We may thus end up moving from the crony capitalism of the present to unadulterated socialism in the future. If that translates into a transformation from a chaotic system of selective law enforcement against political rivals/enemies of the state and their interests as we have today to equal opportunity oppression, such a worsening deficit of liberty would not be what I would call progress. Hence, a balance needs to be found between state and private support (perhaps with a system of matching funds); that way, we could hope to limit corruption while also retaining the obligation of politicians to court individuals and groups with a record of successfully generating wealth.

Thirdly, the tragedy of the commons will continue to be a problem as is classically shown in Tamil Nadu. Opponents have not offered any argument as to how electoral reforms can mitigate it. In fact, if the war of freebies escalates, it could not only bankrupt the exchequer but also undermine any such measures including the state funding of elections. On the other hand, law enforcement measures and spending limits have failed to stem this tide for the obvious reason: as someone said, money, like water, will always find a way to flow. Here again, measures to improve accountability and lower pilferage may be the only way to curb this pernicious trend.

Fourthly, a central flaw of the proposed Lokpal is its overall architecture which is overly reliant on litigation without adequate consideration of alternative methods of monitoring or economic inducements to facilitate official conformity and legal enforcement. Having been drafted by lawyer-activists, this orientation is entirely to be expected. There is a good chance that a bill drafted with wider consultation bringing in smart economists like Kaushik Basu, technologically savvy folks like Nandan Nilekani and experienced bureaucrats could very well think of more innovative ways to curb graft. Since it now looks like the government is in a great hurry to finalize it, this might be an opportunity for the opposition BJP to hold wide consultations and propose something novel rather than simply repeat the same shopworn “aam aadmi” arguments taken straight off the “civil society” handbook.

Fifthly, a clear distinction needs to be made between political corruption and petty corruption that people encounter in their daily lives. There should be zero tolerance for the latter but it needs to be separated from the former which needs a more nuanced approach. Politicians and bureaucrats have different roles and responsibilities to the public and cannot be classed together. With regard to a politician’s role in public life and the implications of funding and conflict of interest issues, I quote below from a publication of the Bar association of New York City:

“The congressman’s representative status lies at the heart of the matter. As a representative, he is often supposed to represent a particular economic group, and in many instances his own economic self-interest is closely tied to that group. That is precisely why it selected him. It is common to talk of the Farm Bloc, or the Silver Senators. We would think odd a fishing state congressman who was not mindful of the interests of the fishing industry — though he may be in the fishing business himself, and though his campaign funds come in part from this source. This kind of representation is considered inevitable and, indeed, generally applauded. Sterile application of an abstract rule against acting in situations involving self-interest would prevent the farmer senator from voting on farm legislation or the Negro congressman from speaking on civil rights bills. At some point a purist attitude toward the evils of conflicts of interest in Congress runs afoul of the basic premises of American representative government.”

As Justice Brennan wrote in United States v. Brewster:

“Senators and Congressmen are never entirely free of political pressures, whether from their own constituents or from special interest lobbies. Submission to these pressures, in the hope of political and financial support or the fear of its withdrawal, is not uncommon, nor is it necessarily unethical. The line between legitimate influence and outright bribe may be more a matter of emphasis than objective fact, and in the end may turn on the trier’s view of what was proper in the context of the everyday realities and necessities of political office.”

A system that fails to recognize this reality is going to either prove unworkable or work to its detriment. Hence, the first step ought to be amending the badly written Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (which casts too wide an umbrella to bring everyone who performs a public duty within its scope) to categorically exclude politicians from its ambit who ought to be dealt with under a different legal framework. The flaw in that enactment is not only perpetuated but indeed made worse by this Lokpal bill which, as it stands, will therefore not make matters any better. I quote here from Justice Byron White’s excellent dissent in the same case regarding the dangers of vesting the Executive branch with authority to prosecute elected representatives for accepting funds or otherwise engaging in what ought to be considered legitimate political activity:

“Congressional campaigns are most often financed with contributions from those interested in supporting particular Congressmen and their policies. A legislator must maintain a working relationship with his constituents not only to garner votes to maintain his office but to generate financial support for his campaigns. He must also keep in mind the potential effect of his conduct upon those from whom he has received financial support in the past and those whose help he expects or hopes to have in the next campaign. An expectation or hope of future assistance can arise because constituents have indicated that support will be forthcoming if the Member of Congress champions their point of view. Financial support may also arrive later from those who approve of a Congressman’s conduct and have an expectation it will continue. Thus, mutuality of support between legislator and constituent is inevitable. Constituent contributions to a Congressman and his support of constituent interests will repeatedly coincide in time or closely follow one another. It will be the rare Congressman who never accepts campaign contributions from persons or interests whose view he has supported or will support, by speech making, voting, or bargaining with fellow legislators…

… To arm the Executive with the power to prosecute for taking political contributions in return for an agreement to introduce or support particular legislation or policies is to vest enormous leverage in the Executive and the courts. Members of Congress may find themselves in the dilemma of being forced to conduct themselves contrary to the interests of those who provide financial support or declining that support. They may also feel constrained to listen less often to the entreaties and demands of potential contributors. The threat of prosecution for supposed missteps that are difficult to define and fall close to the line of what ordinarily is considered permissible, even necessary, conduct scarcely ensures that legislative independence…”

The Lokpal bill goes further than this – it threatens the independence of the Executive branch itself by proposing sweeping definitions to cover crimes that, as he rightly says, may be difficult to define and inevitably involve subjective judgments that can only be made post-facto. All of this is not to suggest that there should be no ground rules about ethics but it is important for any law to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate political activity based on how the system actually works, not some abstract utopian ideal of how it ought to be. A reasonable position is to outlaw the acceptance of contributions as a quid pro quo for political favors that confer unilateral advantage (such as tender contracts) whereas policies or other actions taken to promote the interests of a class of individuals or organizations should necessarily be permitted. The expulsion of several MPs in the previous Lok Sabha for putting up questions in exchange for pecuniary benefit on behalf of a fictitious small business association would be unjustified under such a set of rules.

Opportunistic rhetoric of political parties and the sensationalist tendencies of mainstream media have come together to give the word ‘money’ in politics a dirty connotation (much like ‘communal’) despite it being the eight hundred pound gorilla in the room. Just witness how television channels went to town about Baba Ramdev’s public fundraising without a shred of evidence of any illegality on his part. Unless political leaders and parties grow a spine and come forward to tell the public some hard truths, we are doomed to more drama and bad legislation that will either overdo the cleansing throwing the baby out with the bathwater or else merely give the pretense of cleansing the system without actually doing anything about it. Candor and balance are the need of the day. Will someone bell the cat? The situation is bleak but hope springs eternal….