Culture

Ashwin's Retirement Is His Veritable Doosra

K Balakumar

Dec 19, 2024, 03:40 PM | Updated Dec 20, 2024, 05:57 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In the end, the man called time on his international career as he would bowl his most potent wicket-taking ball in cricket: the carrom ball. You knew that it was going to come. But when it came, it usually caught everyone by surprise.

On the morning of 18 December, with the Brisbane Test still not over, the word was out from cricket media that a big announcement was in the offing. At that moment, the popular speculation was either of Rohit Sharma or Virat Kohli, neither of whom has had a consistently good batting outing in the last couple of series, may announce his retirement. But when images surfaced of Kohli and Ashwin sitting together in what seemed like an emotional chat followed by a hug, the penny dropped.

It was the doosra.

Anyone who follows Indian cricket with reasonable sincerity will feel that Ashwin has a few more years of international cricket left in him. That his announcement has come when an important series is underway, and still in balance, would suggest that this was probably an emotional and rushed decision. Going by his persona, India's greatest off-spinner is not given to doing things in a hasty manner. They say your cricketing style is an extension of your innate personality. Going by that, Ashwin adheres to a thoughtful and patient approach. For someone given to cerebral ways, to call time on his career almost in a huff is bound to raise eyebrows.

Though he has never voiced it openly outside — many props to him for retaining his dignity and poise — Ashwin felt slighted at the inconsistent selection calls concerning him. For a man with 537 scalps in 106 Tests — the second highest wicket taker for India in Tests after Anil Kumble and the second fastest in the world to reach 500 wickets — Ashwin deserved a fairer treatment. Of course, the fact that the other spinner in the reckoning alongside him on most occasions was Ravindra Jadeja — a better bat and fielder — ensured that Ashwin, despite his proven credentials, got the short shrift. (For the record, Ashwin and Jadeja in tandem are among the most potent bowling pairs in the world, and certainly numerically the best in India. The unbeaten home record that India enjoyed for years till it was broken by New Zealand in October this year was owed to the presence and prowess of these two world-class trundlers). The case of Ashwin being left out in favour of an extra batsman or pacer, especially when playing abroad, are too many to bear repetition here.

Ashwin’s SENA Record

His record in foreign lands is sometimes held up against him. But it was something that rankled in his mind too, and he worked on it. He improved a lot in this area in the latter half of his career. For instance, in the landmark series in Australia in 2021, Ashwin picked up 12 wickets in three matches at a good average of 28.83, given the conditions on offer, with a best of 4 for 55. His early dominance over Steven Smith — India's bug-bears in the previous series — kind of set the tone for India's mind-boggling 2-1 series triumph. Ashwin also contributed with the bat, playing that stonewalling innings of 39 not out in Sydney, which helped India save the Test.

In that same year, he was the best Indian bowler in the World Test Championship (WTC) final against New Zealand, by some distance, on a surface where the pacers were supposed to do the job but failed. He picked up two wickets in both innings and even contributed a few with the bat. Jadeja, who also played in the Test, had nothing to show for his efforts. Overall, Ashwin has ended up with 433 wickets in Asia at a scarcely believable average of 21.76. In the West Indies, his figures read even better, with 32 wickets at 19.34. In the so-called SENA countries, his numbers until 2015 were 24 wickets at a 56.58 average, and since 2016, it has been 48 wickets at 31.04 apiece. Despite the improving numbers, something always seemed to work against him when it came to team selection.

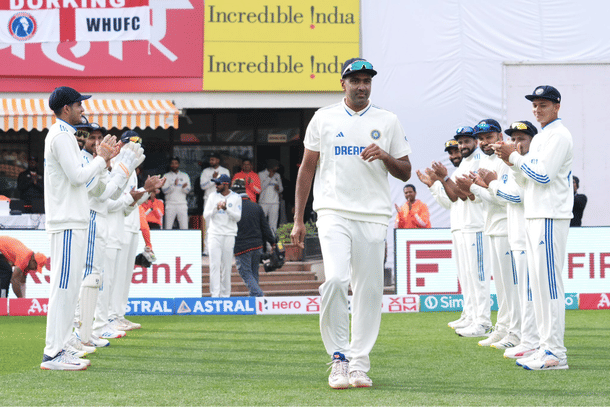

But Ashwin always took those selection whims as any team man would — with nary an outburst or cheap theatrics. His retirement clip put out by the BCCI showed that even when flying out of the tour midway, he had the grace to adhere to some of the time-tested dressing-room traditions of international teams. He made a quick speech, remembering to thank his captain, teammates, coach, and supporting staff, and also had a chat with the rival captain and his off-spin rival in international cricket for nearly a decade, Nathan Lyon. Here was a man who was hurting inside and leaving, but even then he didn't sully the copybook.

Venkat and Ashwin, Kindred Souls

Perhaps Ashwin was following in the footsteps of another celebrated offie from his state, who was also treated shabbily by the system but never resorted to surly or peevish behaviour. S Venkatraghavan had to put up with worse. Once in 1974 in that series against West Indies when the designated captain, MAK Pataudi, was injured, the word then was that six players turned up on the morning of the Test match in the hope of being anointed the skipper. They chose Venkat for the match, and as it happened, they dropped him to do twelfth-man duties the very next Test. No other captain has had to face that kind of ignominy.

And in the aftermath of that tour to England in 1979 in which Venkat was the captain, on the flight back home, the pilot announced — yes, it is a true story — that Sunil Gavaskar had been chosen to lead the team in the next series. Venkat, of course, soldiered on and played uncomplainingly till 1983.

Though, mercifully, Ashwin did not have to face such sorry eventuality, he has a lot in common with Venkat, in that both, engineers by qualification, brought a weighty thinking approach to their cricket on the field. As bowlers, there are many contrasts though. Ashwin had a caboodle of variety and was never afraid to try out fancy and even outlandish deliveries. Venkat was more circumspect and relied on his accuracy, as he could land the ball unerringly on a spot from morning to evening. Also, as a gully fielder, Venkat was splendid. Ashwin's fielding… well, we will not go there now.

But Venkat’s thinking and tactical nous was at least recognised by the cricketing powers, and he was given the captaincy of the team. He led in five Tests and two ill-fated World Cup campaigns in 1975 and 1979. But Ashwin, despite his original ideas, both cricketing and mental, never was close to getting the captain’s armband. After Kohli quit as captain in 2022, there was an outside chance of him being chosen for the top position, but they played it safe with the batsman-captain in Rohit Sharma. Both Venkat and Ashwin were, within the team, known to be outspoken and would not hesitate to call a spade just that. Perhaps such openness did not fit in a milieu where those who operate surreptitiously and through lobbies are more rewarded.

Ashwin is a Legend and Deserves to be Celebrated as Such

Forget captaincy, even praise for Ashwin‘s remarkable exploits seem to come in a less than forthcoming way. But it is a fate that befell Kumble too. For a nation that has been souped up on the exploits of the 'quartet' — Bishen Singh Bedi, Bhagwat Chandrasekar, Erapalli Prasanna, and Venkatraghavan — the spinners who have followed them have been less romanticised in the collective narrative.

But Ashwin's rise in international cricket deserves to be celebrated as that of a legend. Having come into the Indian reckoning in the aftermath of Kumble and Bhajji's (Harbhajan Singh’s) retirement, Ashwin is one of the rare phenomenons who showed that it was not too difficult to move up from the IPL (Indian Premier League) to the Test arena.

His earliest impressions were in the IPL as a CSK (Chennai Super Kings) star from 2009 — perhaps the lone Tamil success in the annals of the Chennai franchise — and from then on, he did not look back in any format. And it is where he will likely end his cricket later.

That he was in the squad for the 2023 World Cup showed that he continued to keep himself relevant in white-ball cricket despite getting a bit long in the tooth. His early-day successes in Tests are staggering. Ashwin took nine wickets in his maiden Test, in which he was 'Player of the Match'. In his first 16 Tests, he collected nine five-fors, and he went on to be the fastest to 300 wickets and the second-fastest to 400, behind only Muthiah Muralidaran. Ashwin and the illustrious Murali were equal in terms of man of the series awards — 11 each.

Just consider these final numbers: Ashwin was the fastest Indian to 200, 300, and 400 Test wickets. He has the most five-wicket hauls in Tests by an Indian spinner (37). He holds the record for most dismissals of left-handed batsmen in Test cricket (268). To his credit is the best strike rate among spinners in Test cricket (50.7). He is one of only 11 cricketers to achieve the milestone of 3,000 runs and 300 wickets in Test cricket. Ashwin has scored a century and taken a five-wicket haul in the same Test match on four occasions. Only Ian Botham with five has done this on more occasions.

As he calls time on his career in the year 2024, his Test bowling average is logged exactly at 24. Just a coincidence. But the stat nerd in him would approve. His international cricketing stint has come to an end, but he will be around as an IPL cricketer (and perhaps also as a TNPL mentor-cum-player) for some more time. After that, he will surely take up some slot in the media. Already he is a popular YouTuber who is comfortable in English, Tamil, and Hindi. A coaching career, with his thinking and honest ways to mentor young talent, cannot be ruled out. Even if he goes out of cricket, you cannot take cricket out of him.

With him, rest assured, a doosra is always around the corner.