Culture

Chettur Sankaran Nair: The Madras Connection And His Landmark Role In The Ashe Murder Case

K Balakumar

Apr 11, 2025, 01:52 PM | Updated Apr 10, 2025, 02:09 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The forgotten man of Indian history is in the news headlines these days.

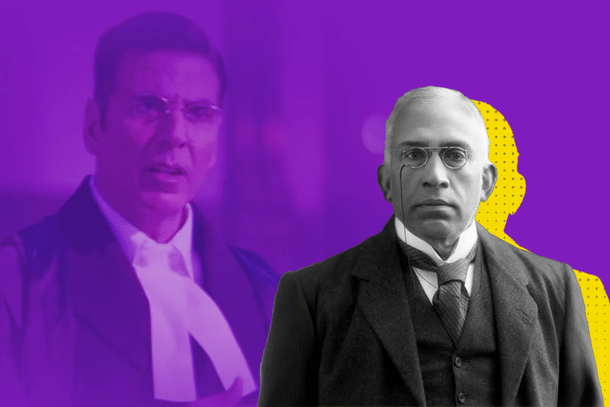

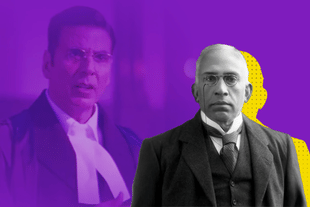

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, the man in question, is being talked about thanks to the Akshay Kumar and R Mahavan starrer Kesari Chapter 2: The Untold Story of Jallianwala Bagh. The Hindi film, which is set to hit the screens next week, is based on Sankaran Nair's cause célèbre involving Sir Michael O'Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

In 1922, Sankaran Nair published a book titled Gandhi and Anarchy, in which he criticised British policies in India, particularly the actions of Michael O'Dwyer during his tenure as Punjab's Lieutenant Governor. This explicitly referred to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of April 13, 1919, where hundreds of unarmed Indians were killed under the orders of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer. O'Dwyer, as the administrative head of Punjab, was seen as complicit in the massacre. The latter filed a libel suit against Sankaran Nair in the King's Bench Division of the High Court in London in 1924.

Kesari Chapter 2: The Untold Story of Jallianwala Bagh is about that case proceedings. The media is awash with all the details of the case that Sankaran Nair lost. He was given an option to apologise to O'Dwyer, but the indomitable Nair chose to take the courageous high ground and instead paid the £500 damages as laid down by the court.

The case, in a sense, brought world opinion to bear upon British brutality in India. So, a towering figure like Sankaran Nair not getting a prominent place in the annals of Indian history is a tad sad.

A defiant jurist in British India

But, for those of us living in Madras, Sir Chetur Sankaran Nair and his family can never be forgotten as their contributions and links to the city are enduring. As a jurist, statesman, and reformer, his contributions to the Madras Presidency and his involvement in the infamous Ashe murder case, whose proceedings happened in Madras High Court. remain pivotal chapters in his legacy.

Though born in Palakkad, Kerala, Nair arrived in Madras to pursue college education at the Presidency College, where he graduated with degrees in arts. He later studied law at the Madras Law College. His legal career began in 1880 at the Madras High Court, where he quickly rose to prominence as one of the most respected lawyers of his time.

And even in those early years, he managed to leave his imprint as a person with his own firm ideas. In his initial days, he worked for the Englishman Sir Horatio Shepherd who eventually became the Chief Justice of the Madras High Court.

As the Independence movement was picking up steam, the mood among the advocates in Madras was decidedly anti-British. They moved a resolution that sought to stop Indians from enrolling as juniors to British advocates. But the rebellious Nair would have nothing of it as he felt that lawyers should be left to decide what they deemed fit. His defiance did not go down well with other advocates, and he was boycotted by them.

His felicity with the language and his strong legal knowledge, however, made him rise up in the profession remarkably, much to the envy of the Madras elites. Nair was appointed public prosecutor (1899) and advocate general (1907) for Madras State and by 1908 he had become a judge of the Madras High Court. During this period, he became a key figure in the Madras bar, alongside luminaries like Sir V Bhashyam Aiyangar and Sir S Subramania Iyer.

Fervent freedom fighter

Even though he did not toe the line of other advocates, it was only as a matter of upholding individual rights. Otherwise, Nair himself was no less a fervent fighter for freedom. His rise as a legal luminary attracted the attention of the Congress that he was its president in 1897 (at the Amaravati session).

Amidst his rising political involvement, he steadfastly pursued his legal profession, and it was he who founded and edited The Madras Review and The Madras Law Journal. The latter is the oldest, most acknowledged legal journal since 1891. Well-known for its prompt reporting of research articles and Judgments. One of his best known judgements as a judge was when he upheld conversion to Hinduism and ruled that such converts were not outcasts.

In 1915 he became a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council. It was a post that was coveted and undreamt for Indians at that time. But Nair got it as a matter of rightful acknowledgement to his acumen as a jurist. Though it was a British post, Nair never felt beholden to them. He resigned from the Viceroy's Executive Council protesting the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre in July 1919 (despite people like Motilal Nehru reportedly telling him not to resign).

In the book Biography of Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, written by his illustrious son-in-law KPS Menon (independent India's first Foreign Secretary), it is well described about how Nair returned to Madras to a hero's welcome after he had quit his post in the Viceroy's Executive Council.

It was in this period in Madras, Nair sat down to pen his now famous Gandhi and Anarchy. To be sure, Nair was not overly impressed with Gandhi's non-cooperation movement. And he opined openly about that in his book. But the book also spoke at length about British brutal highhandedness and abuse of power. (It was so scathing that O'Dwyer sued him for libel).

Nair was not a non-conformist for the sake of it. His positioning came from a deep understanding of law and principles of justice. His stand in the Ashe murder case, earlier in 1911, underscored his value system.

The Ashe murder case and Nair’s dissenting view

The Ashe murder case was, of course, one of the most sensational trials in colonial India, and Nair played a critical role in its proceedings. (The case revolved around the assassination of Robert William Ashe, the British Collector of Tirunelveli, by Vanchinathan, a revolutionary seeking to avenge colonial oppression. On June 17, 1911, Ashe was shot dead at the Maniyachi railway station, and Vanchinathan took his own life shortly after the act).

The trial was conducted as a special case in the Madras High Court (as the victim was a high-profile British ICS officer), presided over by a bench comprising Chief Justice Charles Arnold White, Justice William Ayling, and Justice Chettur Sankaran Nair. The case involved members of the Bharat Mata Sangh, a revolutionary group accused of conspiring to assassinate Ashe.

In a case that lasted for 93 days (from September 1911 to January 1912), Nair's dissenting opinion in the verdict is considered a landmark in Indian legal history. While the majority of the bench upheld the conviction based on the uncorroborated testimony of accomplices, Nair opined against relying solely on such evidence. He emphasised the principles of the Indian Evidence Act, stating that the testimony of accomplices should be treated with caution and corroborated by independent evidence. He felt that the charge of murder had not been legally proved.

"A person should not be convicted except under very special circumstances upon the uncorroborated testimony of an accomplice," he wrote in dissenting view. "The Indian Evidence Act embodies the rules of English law that the presumption must first be drawn that the evidence of an accomplice is unreliable, and exceptional circumstances must be proved to justify its acceptance." Nair's dissent highlighted his commitment to fairness, and adherence to legal fundamentals, irrespective of the nature of the crime or the individuals involved.

Bharathi’s lines and his translation

And in his opinion, he also famously translated in English the vibrant lines of Subramania Bharathi's plucky call to freedom Endru Thaniyum Indha Suthanthira Thaagam (When will this thirst for liberty and freedom be quenched), and Nair also mentioned that the translation did not "convey the force of the original".

Much later, when Simon Commission came to India in 1928, and an all-India Committee of stalwarts which included Sankaran Nair, the latter famously declared to the commission: "Indian political leaders will not delegate their responsibility for framing future Constitution to Englishmen. The destiny of India is in Indian hands, not in the hands of Englishmen".

He (and his son Palat) had a major car accident when they were travelling to Madanapalle from Madras to attend the funeral of one of his sons-in-law MA Candeth in March 1934. He never recovered, and died exactly a month later on April 22, 1934 at the age of 76.

Nair had a huge family, he sired six children, many of whom went on to become well-known names in their own right. Many of them became illustrious civil servants. (Jaya Jaitly was one of his grand nieces). His family, both near and extended one, had strong connections to Madras. Many of his relatives were part of the founding team of the Justice Party, which changed politics in these parts.

The Chennai Aiyappa temple land belongs to his family

Nair himself was no real admirer of Brahmins (against whom the Justice Party was established). Even in his days in the Congress, Nair was unhappy with the domination of Brahmins in it. The Brahmins of Madras also had no love lost for him and did not see eye to eye with him on many matters.

One of his sons-in-law was the well known freedom fighter, journalist and writer, Madhavan Nair (the man who established the Mathrubhoomi daily. He was later a Madras High Court judge and a member of the Privy Council.

He and his wife Parvathi Ammal (Sankaran Nair's daughter) were among the Malayali elites of Madras. She went by the name Lady Madhavan Nair. The couple had a huge property near Nungambakkam. It was called Lynwood Estate, and later became Mahalingapuram. The land that the now famous Aiyappa Temple in Mahalingapuram stands on was donated by the couple. The road near the temple to this day carries her chosen name: Lady Madhavan Road.

Sankaran Nair was religious, but he had no time for dogmas. He was more spiritual in his outlook, and he learnt Pali when he was past 74 to understand Buddhism from its original source.

Till his death, he remained as KPS Menon wrote, "a radical among radicals".