Culture

How Jayadeva’s ‘Gita Govinda’ Inspired The Indian Subcontinent At A Turbulent Time

Kamalpreet Singh Gill

Jun 10, 2018, 08:26 AM | Updated Jun 09, 2018, 06:45 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Commentators and scholars, both Indian and Western, are unanimous in their opinion that the Gita Govinda is one of the finest literary works ever written in Sanskrit, giving Jayadeva the same stature in the Indian classical literary canon as Kalidasa. Composed in the twelfth century AD, the Gita Govinda spread remarkably fast over much of the Indian subcontinent – from Kerala to Punjab, from Gujarat to Manipur – and had a profound influence on the culture and traditions of each region.

What is most striking about the spread of the Gita Govinda to all parts of the country is that it happened during a time when there was no centralised authority ruling over much of India. The period from eleventh to sixteenth centuries, in fact, was one of repeated invasions and political strife in India. Despite that, the text not only spread far and wide but permeated deep into the cultural fabric of each region, transforming life, art, and religion in its wake.

By comparison, the greatest works of Kalidasa were composed during the golden age of the Gupta empire when political stability characterised much of the Indian sub-continent and a centralised authority allowed for easier transmission of ideas.

Jayadeva, the Poet

As is often the case with literary figures of ancient and medieval India, little is known about the life of Jayadeva except that he lived in the twelfth century in Puri, Odisha. Various accounts of his birth mark his origin at either Bengal or Odisha. This lack of biographical knowledge of the poet is more than made up by the wealth of critical work that his most famous composition, the Gita Govinda, attracted. This doesn’t seem to be incidental – Indian poets and writers of the classical and medieval era appeared to have deliberately eschewed fame and limelight by letting their work speak for them. This is perhaps a result of the fact that a lot of classical Indian poetry came under the category of devotional literature, necessitating a quiet retreat into asceticism and the inner world of spirituality. Perhaps it is this spiritual dimension of devotional literature borne out of recluse that gives these works their touch of brilliance.

Impact of the Gita Govinda on Indian Culture

Perhaps the greatest influence of the Gita Govinda on Indian culture is the contribution it made to the development of the tale of love between Radha and Krishna. While the legend of Krishna, the cowherd, and his youthful associations with the Gopis is found in ancient texts, no detailed treatise on the character of Radha existed prior to Jayadeva’s work. The Puranas and certain Sanskrit and Prakrit inscriptions have been found to contain scattered references to Radha that predate Jayadeva, but none of them place Radha as the chief consort of Krishna, nor do they dwell upon the nature of the love between Radha and Krishna. The eighth-century Tamil poetry of Andal contains references to a daughter of Nandagopal who becomes the wife of Krishna, but her name is given as Nappinai and not Radha.

Thus, while Jayadeva certainly did not invent Radha, the contemporary understanding of love between Radha and Krishna is owed entirely to Jayadeva and the Gita Govinda. The work is, in fact, the oldest extant source that celebrates the marriage of Radha and Krishna. Jayadeva was also the first to depict the love between Radha and Krishna as an allegory for spirituality – a theme which was later developed fully by Vaishnava philosophers such as Sri Chaitanya of Bengal and which to this day continues to be the dominant interpretation of the tale.

The development of Radha’s character is pursued by Jayadeva in great detail through the use of various rasas. Much of the drama of the Gita Govinda centres around the sensual play between Radha and Krishna in which Jayadeva uses the concept of “Ashtanayika” to describe the full range of emotions, from the torment of longing to the joy of acceptance that the heroine, Radha, goes through. First detailed by Bharata muni in his Natya Shastra, the Ashtanayika lists the eight different moods of a heroine in relation to her lover. In the Gita Govinda, Radha is presented as experiencing each of the eight moods in turn until she is assured by Krishna that he loves her and no one else. This has enabled the Gita Govinda to become a major influence on the development of classical Indian dance forms. In Odisha, the performance of the Gita Govinda is a central aspect of Odissi, the classical dance form that originated from the temples of Odisha.

The second major contribution of the Gita Govinda has been the development of the Dasavatara as we know them. Like Radha, Jayadeva by no means invented the Dasavatara, which had been expounded on in the Puranas and other early medieval literature. However, the popularity that the Gita Govinda soon came to enjoy in every corner of India in turn popularised the idea of the 10 incarnations of Krishna like never before.

To understand the impact that the Gita Govinda had on India within a few centuries of its composition, it is best to take a journey through each corner of India where the text travelled to and see the multiple ways that it blended into the distinct culture of the region to create unique art forms, from painting to dance to scripture.

Ashtapadi Attam and Sopana Sangeetham – Gita Govinda in the Theatre and Music of Kerala

The Gita Govinda is divided into 12 chapters, with each chapter further sub-divided into 24 divisions called Prabandhas. The Prabandhas in turn are grouped into couplets of eight called Ashtapadi. As a result, when the poem first reached Kerala, it began to be referred to as the Ashtapadi – the poem of eight stanzas – and theatrical performances based on it were called Ashtapadi Attam.

From Ashtapadi Attam developed one of Kerala’s most important dance dramas, the Krishna Attam. Attributed to Manaveda, the Zamorin of Calicut, the Krishna Attam presents the life story of Krishna in eight plays. It is performed regularly at the famous Guruvayoor temple in Kerala. While the Ashtapadi Attam, the original adaptation of the Gita Govinda, itself died out in Kerala with time, in 1985 it was revived by the renowned Chenda player (a percussion instrument popular in Kerala) Kalamandalam Krishnakutty Poduval.

Another major influence of the Gita Govinda in the religious and cultural life of Kerala is the Sopana Sangeetham – a form of classical music from Kerala. Since the Ashtapadis of the Gita Govinda were originally sung at the stairs of the temple sanctum sanctorum (Sopanam), the ritual music began to be called Sopana Sangeetham – the music of the stairs of the sanctorum. Traditionally, these songs were performed behind closed doors, just before the sanctum sanctorum was opened to the public. However, in the early twentieth century, Neralattu Rama Poduval, a recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, broke with tradition and began performing Sopana Sangeetham on the streets, taking it to a much wider audience and thus giving it a new lease of life.

The Gita Govinda in Western India – Rana Kumbha and the Rasikapriya

Rana Kumbha of Mewar is known in history as the fearsome Rajput warrior who restored the Mewar kingdom to its former glory after it had been reduced to insignificance by repeated Turkic and Afghan invasions. Rana Kumbha also built the famed fort of Kumbhalgarh in Rajasthan, often credited with having one of the longest walls in the world. What is less widely known about the Rana is that he was also an accomplished poet and scholar and is credited with having composed perhaps the best-known critical commentary on the Gita Govinda, called the Rasikapriya.

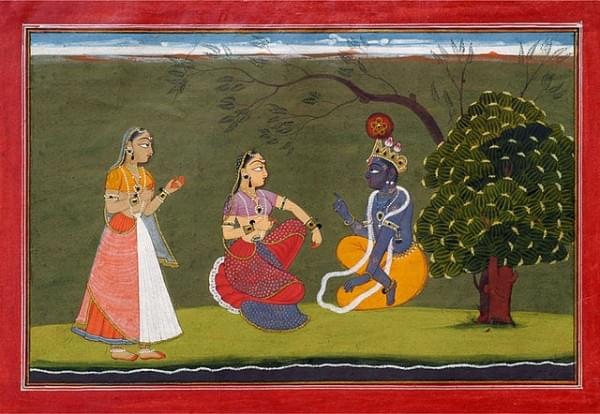

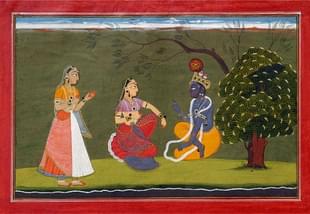

Rana Kumbha’s treatment of the Gita Govinda besides its literary merit also sparked off the golden era of Rajput paintings in the next century as artists inspired by the sensuality and richness of emotion in the tale of love between Radha and Krishna attempted to commit the poetry of the Gita Govinda to canvas.

Punjab – The Sri Guru Granth Sahib and Pahari Paintings of the Himalayas

By the fifteenth century, Jayadeva’s poetry had become so popular that its influence was felt even far north-west of the Indian subcontinent. According to the Sikh tradition, the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak Dev, on his travels across South Asia arrived in Puri, where he spent some time studying the Bhakti tradition inspired by Jayadeva, and collecting devotional hymns. As a result, two of Jayadeva’s hymns became a part of the Sikh holy scripture, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, where the poet Jayadeva appears as Bhagat Jayadeva. Guru Nanak’s teachings became immensely popular in the north and influenced all aspects of tradition and culture in the region.

From the late seventeenth century onwards, the popularity of Jayadeva reached the isolated Himalayan kingdoms surrounding Punjab, leading to the blossoming of a school of painting in which intricate, lyrical depictions of the themes of the Gita Govinda produced a unique style of art known as the Pahari paintings. After the Rajput paintings of western India, and the Mughal paintings centred around Delhi and Lahore, the Pahari paintings are the most important school of painting in northern India. Besides themes from the Gita Govinda, the Pahari painters also depicted the life and times of Guru Nanak as well as stories of his travels across the Indian subcontinent.

Eastwards – Gita Govinda in Nepal, Manipur, and Bengal

One of the earliest manuscripts of the Gita Govinda was found in Nepal, dating back to 1348 AD. Thus, in less than a century of it composition, the Gita Govinda had travelled as far as Nepal, where it began to be sung during the spring celebration in honour of goddess Sarasvati.

The Gita Govinda has influenced classical Manipuri dance forms too. Maisnam Amubi Singh, one of the foremost exponents of Manipuri dance in the twentieth century, composed many classical solo dances based on the Gita Govinda. He was the first winner of the prestigious Sangeet Natak Akademi Award besides being a Padma Shri awardee.

The erotic mysticism of the Gita Govinda was a major influence on the Vaishnava saint Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who took Jayadeva’s philosophy to every corner of Bengal. This philosophy envisages the longing of Radha for Krishna as the separation of the human from the divine and the reunion of the former as the ultimate spiritual goal of the latter. This theme of the allegorical spirituality of the love between Radha and Krishna was further developed by Chaitanya’s followers and with time became the bedrock of Sri Chaitanya’s Vaishnava reformist movement in Bengal. The recital of the Gita Govinda is also an essential part of the ritual prayers offered at the Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha.

We can see that what was remarkable about the mobility of the Gita Govinda was not just its geographical spread, but also its ready transmutation across almost every form of multimedia known to pre-modern man – word, sound, colour, and movement.

Remembering Jayadeva Today

The first English translation of the Gita Govinda was published in 1792 by the philologist William Jones, who was also the first person to suggest a common root for Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek, and coined the term ‘Indo-European languages’. From Jones’ English translation, the Gita Govinda was translated into other European languages. The German writer and statesman J W von Goethe wrote that he found remarkable the “extremely varied motives by which an extremely simple subject is made endless”.

This simplicity of Jayadeva’s work was perhaps what allowed it to have so deep an impact on Indic cultures. Unlike classical poets like Kalidasa and Bhartrihari, whose work was complex and accessible only to a cultured audience familiar with poetic techniques and capable of understanding the linguistic subtleties of Sanskrit, Jayadeva’s work intersected with folk and popular mediums of expression and became accessible to a far wider audience.

If there is a poet of India whose work has inspired a whole nation, it has to be Jayadeva. Kalidasa of ancient India might perhaps score on technical brilliance of his poetry, Tagore in the modern world might have had a larger audience and greater popularity, but few works of literature have had as great an impact on a civilisation and its culture as Jayadeva and the Gita Govinda. What is even more significant is that Jayadeva’s work helped bind a civilisation together at a time when it was undergoing a time of political turbulence due to repeated foreign invasions. In its search for a pantheon of national heroes though, the modern Indian nation appears to have completely overlooked the contribution of Jayadeva.

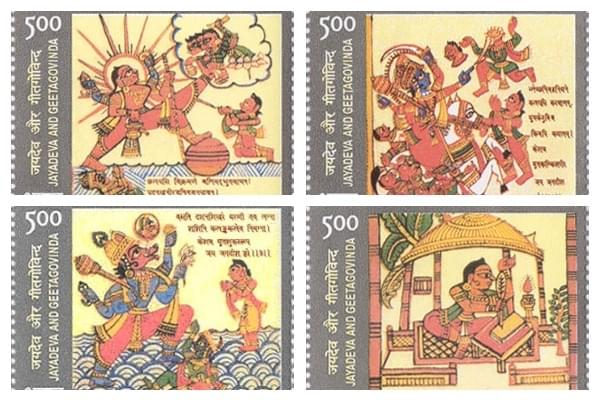

In 2009, the government of India issued a series of 11 stamps in honour of Jayadeva. Ten stamps feature each of the 10 Dasavataras while an eleventh one shows Jayadeva composing the Gita Govinda.

Kamalpreet Singh Gill is a regular contributor to Swarajya. His areas of interest include history, politics, and strategic affairs. He tweets at @KPSinghtweets.