Culture

How Prasad Pawar Restored Art Work In Ajanta Caves Without Touching Them

Sumati Mehrishi

Feb 03, 2018, 07:44 PM | Updated 07:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

When Nashik-based photographer, artist, restorer and archivist Prasad Pawar comes across a deteriorating work of art in the Ajanta caves, he finds it hard to relate with the form, and decides to give the painting a new life.

“How can we not do anything when Ajanta is fading and moving towards darkness?” he asks.

Prasad is on a continuing mission. He has dedicated 27 years of his life studying and digitally restoring the vanishing art work in Ajanta caves – heritage that may cease to exist as time goes by.

During these 27 years, the artist has recorded the 2000-year-old paintings, our national treasure, through his cameras, over several visits and revisits to caves 1, 2, 16 and 17. He has studied and restored works of art that have become physically irreparable and have lasted, “miraculously”, for 2,000 years of Indian history, art history, performance of music and dance, philosophy, traditions, painting, skills, styles, colours, life, interaction – 2,000 years of art of storytelling and the tradition of tales.

Prasad says, “At this rate of deterioration, the paintings, India's oldest known, would not last for more than three generations.”

A collection of his works, ‘Glorious Ajanta’, was displayed recently in collaboration with the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA).

Prasad is ready to go further with “Atta Deep Bhava”, his initiative to help people connect with the recreated works through the original colours, hues and stories, from the caves to galleries in India and outside. At this juncture, he is calm, assertive, more passionate for deeper details and dimensions and more determined to make people aware about what they have viewed inside the four caves in Ajanata, the UNESCO-designated world heritage site in Aurangabad.

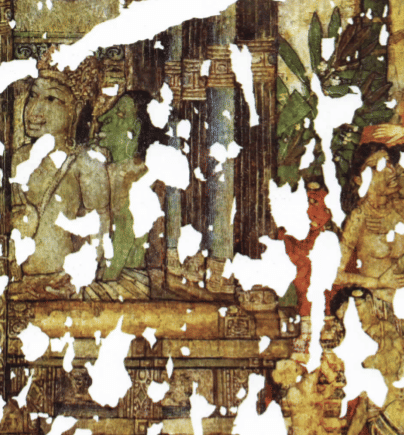

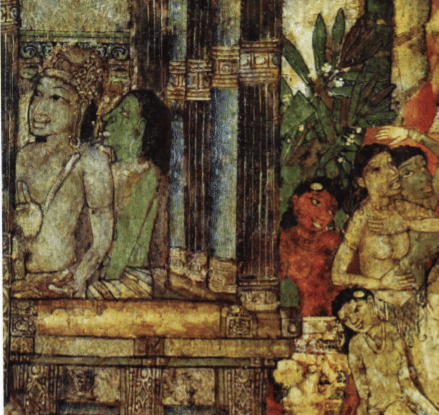

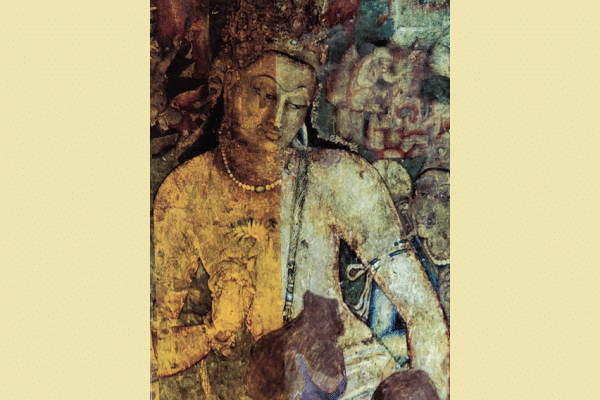

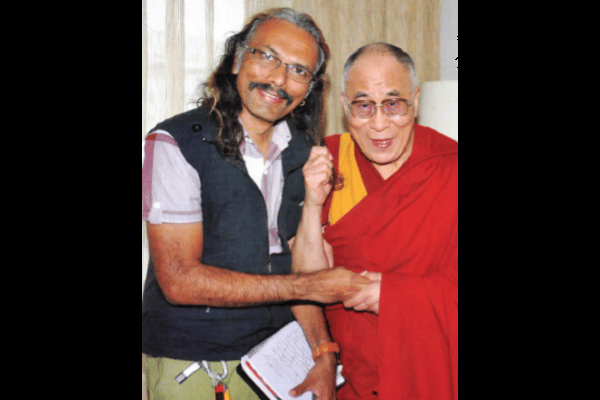

On the last day of Glorious Ajanta, when Swarajya visited the IGNCA galleries, Prasad had invited a special guest – National Museum director general B R Mani. Mani took a tour of Prasad’s pioneering work and was left overwhelmed, emotional and impressed. Reproduction of the iconic portraits from Ajanta caves, Padmapani, Vajrapani, Black Princess and many other art work paintings from caves 1, 2, 16 and 17, depicting scenes from the Jataka tales, such as Buddha giving sermons, the serpent form of Bodhisatva, several episodes of Buddhas’ life, appear to the viewer as (physically) restored, their colour and composition visibly saved and reclaimed, remaining as close as possible to the original. No physical touch was involved in this restoration; it is something Mani, himself a noted conservationist involved with the restoring of caves 16 and 17 during the late 1980s and other iconic projects, has never seen before.

“I was part of the team that was examining the deterioration in caves 16 and 17. Parts were destroyed by Italian conservators, who used shellac and other chemicals which were deteriorating the paintings,” Mani says. At that time, according to the veteran conservationist, his team was not only involved in structural conservation and stabilising the rocks, but were putting their minds together on how to control the damage to the paintings. Back then, Prasad was still preparing to get into an art college, when his life would change after examining a portrait from the Ajanta caves.

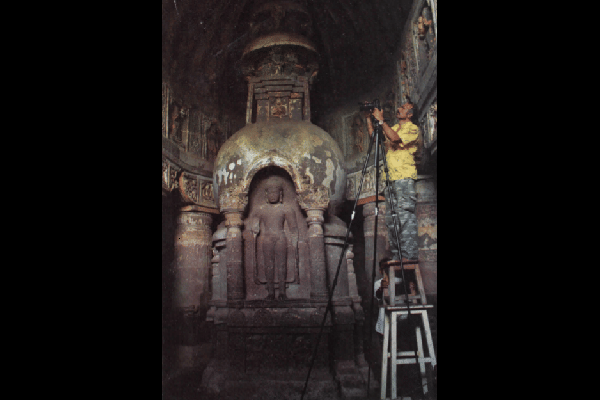

Looking at the damaged iconic portrait, Black Princess, known for her charm, sensuality, headgear and ornaments, and the restored version, Mani calculates the number of hours Pawar would require to digitally record some of the works in the four caves through photography, given the low light and space limitations, particularly the scenes from the Jataka tales. “It took me a year to photograph a particular Jataka, sir. The sun would move slowly through parts of the painting, every two months. For other works, I would depend on the tripod, the sun and the right timing. Interestingly, parts of art work near the ceiling are in better condition owing to distance from human access, heat and other factors responsible for deterioration,” Prasad adds.

Prasad’s is an eternal journey dedicated to the colour, form and lines of the Jataka tales in the Ajanta caves. He walks, tirelessly, between photographic evidence and tangible reinterpretation of existing heritage – an exercise in restoration that begins on the bindu – of the camera aperture, and grows under research, light and digital restoration in his studio in Nashik. Yet, his appetite for seeing the purest in form is still huge. “Mr Mani and his team have been fortunate to see the paintings in better state. Inhone bahut hee pure material dekha hai (They have seen a very pure material)”, he tells Swarajya.

The documentation and restoration of paintings in Ajanta caves undertaken by Prasad is a story of patience, immense handwork, thousands of hours spent in detailed research of Buddhist traditions and art, and a gruelling process of completing a narrative. “I wanted to see what actually was available in art 2,000 years ago. We have been storing our civilisation in art. Art gives us all the answers we need about those times,” he adds.

The exhibition has been put together simply for viewing and awareness. He explains, “Hai kya aur dekhna kya hai in the dark (It’s about what’s available and what’s to be viewed in the dark)”. People who visit Ajanta get the ‘feel’ of being at the monument. They can barely manage to have a cursory look due to the low intensity of light, which, currently, is only 5 lux. They spend nearly 10 minutes on viewing. To appreciate these paintings, a viewer needs to read, register and recall. “At least people who work towards strengthening the Indian art narrative today should be able to spend more time on details in these works that were left for us 2,000 years ago.”

Prasad’s digital restoration work and process primarily seeks recreation and restoring – a meditative process that has given 'viewing' of art a new meaning. “There are many stories which I want to decode and know their references. These four caves had paintings and stone work existing simultaneously. This is something unique to the Ajanta caves. Working on them, I get the same bliss, anubhuti, and joy of creation, as any devoted artist gets when he plays the sitar,” he adds.

For 10 years, he has been digitally restoring the art works through a process that involves putting back details missing in the paintings and their parts affected by deterioration. “It is important to store what I photograph. It is important to store what I rework on those photographs. It is done as per scales used in the original paintings and stone works. Sketches are made in pencil. Colours are filled. Everything is stored again,” he adds.

His aim – to complete, place, reunite and reclaim the missing sections through rework on photographic evidence, based on his study of the visual evidence collected over the years. It is a three-fold path. Visual documentation of the art works – done through photography. Photographs (from his abundant collection) are studied and paintings recreated with colour correction. These are restored and documented in consonance with the original – with immense sensitivity.

Where did it all begin? “The realisation came during the first year of college. I was studying art. I came across the famed Padmapani painting and noticed that portions were missing. There were two patches – one on the stomach of the iconic figure, another on the left hand. I approached my lecturer and told him how, as Hindus, we are told that it becomes difficult to connect with a depiction of a god or goddess when it is portions or sections, broken, destroyed or missing. I told him that I would like to complete the form and replace the patches with what the artists of those times would have created or imagined. He said, ‘You are too young’ to think of recreating these.”

This interaction was a trigger. “I went to the caves that are believed to represent scenes from Buddha’s life. The scenes are heavily drawn from the Jataka Tales. My life had changed.”

The paintings left him speechless, and their natural deterioration, dejected. He had two options – to continue feeling dejected while being aware of what he could do for the monument, or to start restoring them for younger generations. “I wanted to preserve Ajanta at any cost,” he adds. How did he afford the equipment? “It has all come from my pocket. I have used cameras as per my needs, from Canon to Hasselblad. I have taken no help from the governments in 27 years.”

Prasad had a broad canvas and original insight from the paintings as his material. Material threw open elements – elements to be shot, elements to be used, to fill scratches, scrapes and stretches of colour, hues and form, elements to be rethought and placed, like missing pieces in a jigsaw that’s 2,000 years old, a jigsaw in which you can arrive around the colours, not on them, a puzzle that requires understanding, observation, perception more than 'solving' or mindless and cold 'fixing'.

Physical restoration was not impossible for Prasad, but it was not feasible. He requested the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which manages the monument, for permission to photograph the art works for digital restoration. “ASI granted permission for documentation work in 2006. I took permission to work for a few hours and told them that I want to do something. I had a Canon at that time.” It was time to put all the clues and links he had collected over the years, together. “We can't make an Ajanta today in spite of the tools, time and techniques available. Why? Wo junoon aaj nahin hai (we don't have that madness today). Back then, those people were guided by one thought – how to help the other person. There was tatva, a system, a sense of sacrifice, surrender, associated with every Jataka. History books tell you a story of a king and queen. The Jatakas go much deeper. You find elements that give you details and more details on the lives of people – a window to how life was in Bharat 2,000 years ago,” he adds.

Prasad’s work rests magnificently on research photography, his travels across the country, interpretations, reinterpretations, recall, memory, consultations from experts worldwide, and intuition. The intuition, it becomes clear when one examines the blown-up reproduction of his work, is not a plain echo left to wander in time and antiquity in Ajanta. It is measured, precise, free and controlled, living and growing continuously in neat resolution – in the endless chain of strokes and layers of painting and digital rework. Intuition came with knowledge, and part of knowledge, with travel. His work gives the viewer a reason to rediscover the power of intuition in art, photography and research photography.

It is the intuition of an artist who can throw himself from the 22 foot camera tripod, back 2,000 years, and paint a narrative of those times, several times over, year after year, even when his hands are busy adjusting the camera lens.

Prasad has been able to immortalise a part of heritage that took birth in a continuous evolution of art, human endeavour and thinking, spread over not decades but centuries, in the Ajanta caves. How did he connect the missing links in the restoration work? He drew the thought, direction, inspiration and clues from the Jataka tales – the basis for his restoration. How would he travel back in time to relate with aesthetics, form, bhaava, messages, intricacies and moods? By travelling. “I had to see what all existed 2,000 years ago – a civilisation through art, as it has been stored, in art. Then, languages. Material and stories on Jataka tales are available in Pali, Brahmi lipi, Sinhali, Marathi, Sanskrit, Tamil and English, but details about the people are missing. How does the raja look? What is he wearing? We need to look into those details. Artists of those times could go into such detailing. I found evidence to connect these dots all over India.”

The artist took a journey across India, covering 35,000km through Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan, to study the colour palette, “the psychology of artists” of the time and to understand how they created characters, situations and scenes. He adds, “When you are looking at art which originated 2,000 years ago, you need to have some evidence to work with. You can go back in memory to a decade. But when you need insight on Vaastukala, ornamentation, clothes, etc, you need evidence. I collected references before beginning the research work on Ajanta and Ellora,” he adds. His circuitous romance with distance and proximity with art works became more intense with travel, so did the cyclic churning of inclusion and conclusion.

Today, the work is being carried out day and night, reducing the distance between the monument, moment and the visitor, the viewer and art, reality and illusion – the illusion that the distant and short viewing of Ajanta would leave many visitors with, the illusion left on the viewer’s mind, like a reverie, in pale glow. How are the colours and hues matched? “The colour correction is done up to the original, as per the placing of Jataka story and the part photographed inside the caves. The distance of the doors and windows and the natural light falling on them is an important factor that helps determine the colour details for recreation and matching. Colour temperature of the lights are checked. The paintings have faded due to various factors. They have turned yellow. Digital correction for better clarity is carried out.”

Why are his projects under Prasad Pawar Foundation significant to Indian art and history? They are a result of an extensive study of art that unravels details on narration, spiritual journeys, people, colours, skin colours, fabric, prints on fabric, ornaments, clothes, material, metals used, weapons, artists, musical instruments, the arts, hierarchies, moods and lives. He has poured the study on the canvas. The dimensions in the Viharas he has photographed in the Ajanta caves and reworked, give you room. They accept the viewer.

Then, Prasad has entered the paintings – not in fantasy self-portraits or in contemporary footprint forced on an ancient canvas. He has entered the paintings and their time with the devotion of a pilgrim, patience of a yogi and perseverance of a student of the arts. He is drawn to the physicality in art – in the kriya, the doing, and grammar. “I work on wood, metal and stone. I wanted to know how a chisel mark culture is made in art dedicated to Buddha. What is the process? I studied the chisel mark. I studied both painting and sculpture. I find bliss in both chisel mark and painting.” He is restoring the unrestored as well as restoring the restored.

He, still, has miles to go. “More than 14,000 square inches of work is over, and 223,200 square inches remains of just cave 1.” Will the exhibition travel? “Yes. I am going to focus on the display of this work and take it to more and more people. I also plan to take it outside India and create a museum in Maharashtra,” adds Pawar.

At the end of his tour, Prasad touches Mani’s feet in a mark of respect to the veteran conservationist. That’s how one of the greatest artists of our times, unsung, in a scene dominated by contemporary expressions and their celebration, counts blessings. Prasad is an artist immersed in Indian art narrative. He is giving back to Indian art history more than what he draws from it, and won’t sit idle while a tangible tradition fades and moves towards darkness. He concludes, “There is no tool to measure spirituality. This is where I am in my work – a state of ananda.”

Between the cosmic ‘before’ and ‘after’, between the conservation and recreation, between the several steps in Prasad’s work is a celebration of a civilisation that takes you to second-century BCE. Celebrate what remains and is restored.

Sumati Mehrishi is Senior Editor, Swarajya. She tweets at @sumati_mehrishi