Culture

How The Sari Went Out Of Fashion In Pakistan

Deviyani G

Aug 15, 2021, 11:49 AM | Updated Oct 18, 2025, 10:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

There is no other piece of garment that is quintessentially Indian than the sari.

This continuous piece of cloth that comes in variants of six to nine yards has distinctive drapes throughout the subcontinent. It seems to be as old as time itself, an heirloom of the past that thrives in the present.

While the sari has been celebrated to the point of reverence in India’s 75 years of Independence, with the renowned designer Sabyasachi Mukerjee even declaring:

I think, if you tell me that you do not know how to wear a sari, I would say shame on you. It’s a part of your culture, (you) need stand up for it

It has had a slightly more tumultuous journey in the ‘Land of the Pure’. The sari today can be counted amongst the many casualties of India’s Partition and thereafter, the consecutive bouts of Islamisation of West Pakistan.

Post creation, the Islamic republic witnessed the sari skim through its societal and political circles alike. The country’s elite began to wear it as formal attire.

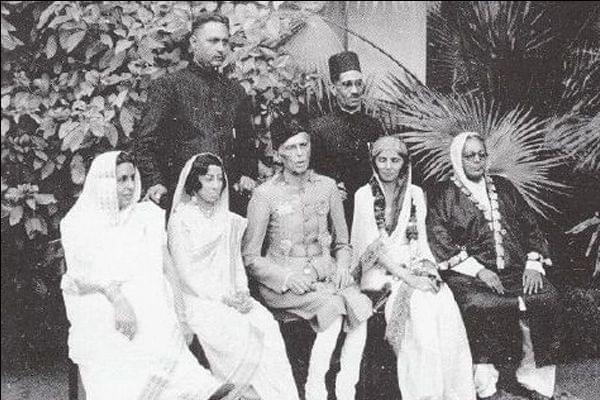

For military wives, politicians, musicians, actresses and models, it was a ‘must have ’. It used to feature in the wardrobes of Pakistan's matriarch and Muhamad Ali Jinnah’s sister, Fatima Jinnah, and General Ayub Khan’s daughter, Begum Nasim Aurangzeb (who used to often wear the sari during official visits abroad).

In fact, up until the 1970s, it was an accepted form of dressing in the upper echelons of 20th century Pakistani society, regardless of religion or ethnicity.

The decline of the aspirational status of the sari began with the dawn of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s ‘Awami’ look or the ‘People’s Suit’.

He advocated for the Salwar Kameez in a bid to divorce the growing influence of the west and promote what he thought was an egalitarian dress code for the men and women of Pakistan.

What truly led to the alienation of the sari was the reign of Zia -ul-Haq. The General who seized power from Bhutto (and eventually hanged) in a military coup in1977 ruled for a decade during which time he Islamised Pakistan's legal system, economy, education and fashion.

He is known for attempting to reduce the worth of a woman's testimony by equating its value to half of that of a man’s, banning makeup, forcing women TV broadcasters to cover their hair and prescribing the percentage of time (25 per cent) women could appear in commercials.

It was his declaration of saris as 'un-Islamic', which incentivised their fade out of Pakistani public life.

Later, when Benazir Bhutto entered into prominence, she too adopted the staple Salwar Kameez, which she often paired with a boxy jacket. However, her mother Nusrat Bhutto continued to flaunt saris for the rest of her life.

In Pakistan, saris today are associated with being ‘Indian’ and by that extension ‘Hindu’. Just like bindis, bangles and the mangalsutras, they too have become markers of identity.

While there is some talk of revival, the rare sight of a sari would usually be somebody from the older generation of Hindus, Zoroastrians or Muhajirs (Muslims originally from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or Hyderabad) in the cities of Lahore and Karachi.

The taboo makes the young fearful and the double takes, uncomfortable.

This is in contrast to the developments that occurred in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

The Bengali sari, which was first introduced and popularised by Jnanadanandini Devi, the wife of Satyendranath Tagore, is a distinctive part of Bangladeshi culture.

During the 1971 war for liberation, it became a symbol of defiance. Women in crisp white saris would march in straight lines with rifles in their hands to take part in the Mukti Juddha.

The difference in language, culture and the sari was evident. For that matter, it was common for Muslim women of the time to don the red dot on the tip on their foreheads just like their Hindu counterparts.

Some Bangaldeshi Muslim women continue wear bangles, saris and the tipa, though the orthodoxy has managed to introduce the chaodora and abaya — along with the erasure of bindis — to a significant portion of the population.

When Sushma Swaraj was Minister for External Affairs, she and Bangladesh Premier Sheikh Hasina Begum indulged in what was termed ‘sari diplomacy’.

The two women gifted each other saris, the deeper significance of which established the contribution of women in strengthening bilateral ties.

While there exist regions in the subcontinent where the quest for the normalisation of the sari persists, India boasts of a rich diversity of traditional embroidery and weaving techniques, which has resulted in centuries of continuous production of saris such as the Kanchipuram (Konjeevaram), Mysore Silk, Pochampalli, Jamdani, Blucher, Pithani, Benarasi, Bandhini, and Sambalpuri among various others — A cause for celebration indeed.