Culture

Interview: Veena Maestro D Balakrishna, Who's Passionately Taking The Mysuru Baani Ahead

Ranjani Govind

Oct 08, 2022, 01:09 PM | Updated 01:09 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Music concerts from senior musicians, lec-dems on instruments and talent promotion concerts will mark the fifty-second Music Conference of the Bangalore Gayana Samaja from 9 to 16 October.

While Vainika D Balakrishna will be conferred the ‘Sangeetha Kalarathna,’ senior Mridangist M Vasudeva Rao will be awarded ‘Karnataka Kalacharya.’

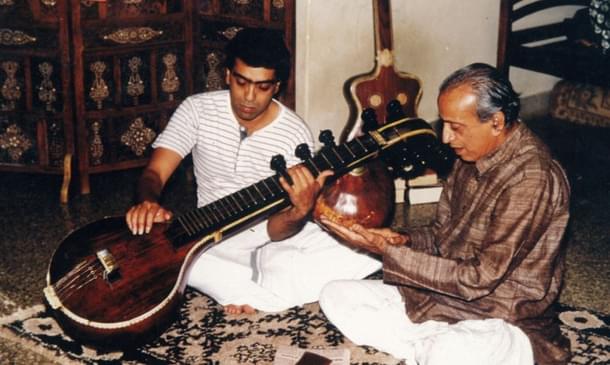

D Balakrishna stepped into his father’s shoes to take forward the Mysore baani of the veena; as an A-Top artiste of All India Radio, he created a niche for himself adding distinguished sparklers to his solo presentations and expand his traditional contours.

His signature streaks had him recently curate a musical video on YouTube ‘Aikyamrutam’ as a tribute to commemorate India’s seventy-fifth year of Independence with an assortment of songs representing various states, featuring pictures of freedom fighters, famous personalities and monuments.

While one see’s him often sharing the Carnatic stage with his flautist nephew Vamshidhar, music connoisseurs have not forgotten the multihued Sarasaangi and Nat-Behag at the jugalbandi platform he shared with Sarod maestro Rajeev Taranath.

His pancha-veena shows with his students, pioneered by his father, is another feature of veena he has kept alive, while popularalising the Saraswati veena itself is his raison d'être.

That’s the multi-faceted Vainika D Balakrishna, whose long interview (at the Ananya Cultural Academy, Malleswaram, Bangalore) opened several doors of learning for this reporter as one listened to his veena speak, and the vainika sing gracefully while he demonstrated as we spoke.

Balakrishna, born in 1955, grew up in Hale Agrahara Mysore in the house of his grandfather Venkatesha Iyengar, also a royal court musician.

He is armed with M.Sc. in Statistics, worked for RBI, and is now coaching a host of students around the globe, some of whom are graded artistes of the All India Radio.

He passionately pursued his family’s musical legacy alongside his job to become a torch-bearer of the Mysore styling and take the school forward.

Balakrishna was at ease, modestly accepting my congratulatory wishes for being selected for one of India’s treasured musical honours, ‘Sangeetha Kalarathna’ to be bestowed on him by The Bangalore Gayana Samaja, 117-year-old and amongst the oldest running music sabhas in the country.

The Samaja’s Music Conference will during its valedictory ‘Vidwath Sadas’ confer the title on him. Balakrishna is also the Conference President of the Sabha’s annual musical extravaganza where he has curated many aspects of the programming, especially the academic lec-dems on instruments from senior practitioners of music.

Balakrishna’s father, Veene Doreswamy Iyengar, whom he was trained under, was the first veena player in the country to be featured in the Akashavani National Programme of Music in 1953 when AIR had flagged off the national series that added a feather to Karnataka’s pride.

Iyengar was also the earliest amongst the Mysore Royal Court Ashthana Vidwans, even as his guru Veena Venkatagiriappa had made his mark in the royal portals.

D Balakrishna spoke in an exclusive interview to Swarajya ahead of his receiving the Sangeetha Kalarathna from Gayana Samaja this weekend. Here are some excerpts of the man and his music, and the honesty that marks both.

The award must be more gratifying to be received now when the Mysore baani is being taken forward by you, after your farther…

Balakrishna: It is an honour that this biggest Sabha award of Karnataka is being bestowed on me. I am grateful to Gayana Samaja and my guru/father for this.

And it’s a glory and credit to be amongst the Kalarathna league of musicians such as Gangubhai Hangal, Dr Ra Sathyanarayana, Lalgudi G Jayaraman, L Subramaniam and Rajeev Taranath amongst others who have earlier received the award.

Your father’s musical standing is of great value to you for taking to the instrument?

Balakrishna: As we unfold the history of our musical parampara, it’s rewarding to see that we have been perpetuating a heritage.

My father, Doreswamy Iyengar, a student of his father Venkatesh Iyengar and later Venkatagiriappa, has seen both the era’s - the serious music that received royal patronage from the early 1930s to 40’s, to concurrently having sabha concert presentations.

In 1940, he had started broadcasting on AIR-Trichy for receiving people’s patronage, a time when music had just started emerging as an entertaining medium. My father was still the Asthana Vidwan at the Mysore Royal court until Krishnaraja Wadiyar’s time.

In 1955, he came down to Bangalore, reluctantly leaving Mysore, when he was appointed as Music Producer at AIR Bangalore for a monthly salary of Rs.450.

BV Keskar, the then Information and Broadcasting Minister in the Nehru government had wanted my father to join the Radio, after he heard him on the National Programme.

You started off with the mridanga?

Balakrishna: My father had hardly asked me to play the veena as I had started my mridanga classes with vidwan CK Ayyamani Iyer as my parents noticed a flair for laya, even as they tolerated my beats on every vessel, table or book.

But before my teens, I figured my heart for the veena, and secretly played on it in my father's absence, without learning from him the formal way. My father was strict; he hated the fleeting romances I showed towards mridanga and many kinds of sport.

Surface-level interests don’t help, realise your true interests and feel the artistic pleasure before jumping into learning, he would say. It was providence that once when I played something on the veena to my grand-uncle from Mysore, he convinced my father to teach me the veena.

“Rama Nee Pai” in Kedaram started off, even as my father was particular that I had a job to fall back upon, and not made music my mainstay.

Iyengar’s rod of discipline had both its positive and negative effects on your musical career?

Balakrishna: I treasure his single-minded drive to lead me on to the time-honoured styling. There were many aspects that my father intrinsically believed in. He always screened his students to actually gauge their fundamental interest in music, but would strictly not waste his time otherwise.

Until 18, I had informal lessons, and he strictly started teaching in vocal first to have me absorb the nuances, and followed it with the veena as the Mysore styling is a blend of vocal and instrumental.

More often he would find mistakes and correct me, but his frown and impatience unnerved me. With a charged mental battery my focus was just in following and playing with him.

He expected students to learn with a single teaching, and often said 'Where is your focus?’ My confidence would be punctured, and I would commit more mistakes.

Even with my father giving up on me multiple times, I did not lose hope. This was my positivity, a lesson that all students of music should emulate. As a guru now, I intentionally give my students a lot of freedom so that their creative instincts get shaped without the fear factor.

What were his expectations as a disciplinarian?

Balakrishna: My father held that every strum on the veena and every pluck of the tala strings have an implication to the said Mysore styling. Nothing is done for fashioning a trend here.

There were times I would invite a nasty glare with a wrong twang, with my father complaining that futile modernisms were divorced of classicism. It’s not that he was against smaller compositions, or peppy tail-enders as Raghuvamsa Sudha, a tillana or a Dasara-pada, the mass appealing numbers that were celebratory towards its composers.

His contention was ‘get your musicality right, don’t just copy, your creative alleys have to be raga, tana, pallavi and the kriti taken up the right way.’ Your Bhairavi or Todi have to convey their stately make-up, while being educative towards your audience.

Nayaki will not lend itself to be expanded beyond a sketch; a perfect Narayanagowla is a tight-rope-walk between Ketaragowla and Suruti; or Jayantasri seems so much Hindola in the ascent with the panchama adding to its character in the descent.

If a student is serious, he should concentrate on such finer distinctions, and that he said can be imbibed by listening to yesteryear greats.

Can you detail the stylised Mysore baani, and who are the musicians we can trace here?

Balakrishna: Mysore has given its name to one of the four important veena styles in south India.

Similar to the gharanas of Hindustani music, these four styles – Tanjavur, Mysore, Kerala (Tiruvananthapuram) and Andhra (Bobbili-Vizianagaram) – evolved in the four major centres where vainikas converged under royal patronage.

Coming to the characteristics of the Mysore baani, the tone is more treble with lesser base. With straight notes for preference and the use of many strings at a time, the right hand uses a lot of meetus (strokes in between sahitya syllables for instrumental effect) done with finger nails.

The gamakas are with far lesser deflection of strings with pull of just two notes in one fret. The instrument gains a musical personality with split fingering technique used, as against the vocal style of singing with an excess of gamakas.

In Mysore styling, imitating the vocal delivery will not help one tap the instrument’s potential.

The vainika-trio Veena Shamanna (son of Rama Bhagavatar,Thanjavur asthana vidwan who sought Mysore royal patronage) and his sons Subramanya Iyer and Venkatasubbaiah were gurus from the same family to three generations of Mysore Maharajas.

Other veena luminaries of the Mysore royal court at the time were Padmanabhaiah (1842-1900), Seshanna (1852-1926), Subbanna (1861-1939) and Chikka Lakshminarayana.

All through the reign of the Wodeyar dynasty, classical music, the veena in particular, enjoyed royal patronage. Kannada Poet Laureate BM Sri hailed Mysore as “Veeneya bedagidu Mysooru” (veena’s grace, this Mysore).

My father also spoke of the Mysore baani tracing to Pacchimiriam Adiappayya, the Kannadiga who was the court musician of the Maratha Kingdom of Thanjavur in the eighteenth century.

His descendants were V Das of Vijayanagaram and Veena Seshanna of Mysore. Veena Venkatagiriyappa, my father’s guru, learnt under Veena Seshanna who was also the Mysore Court musician.

Adiappayya was a prolific composer of Carnatic music with the Attatala Bhairavi varna to his credit and his famous disciples were Syama Sastri of the Trinity composers, and Ghanam Krishna Iyer.

Was it a struggle to take a bypass from the notable veene-Doraiswamy Iyengar mould for you?

Balakrishna: From 1973 onwards I started accompanying him and my first was at Bidaram Krishnappa Ramamandira in Mysore, thereby becoming his shadow. The next 15 years saw us take up nearly 70 concerts a year throughout India and abroad to people’s awe.

Nevertheless, one day, Kannada playwright Pu Ti Narasimhachar, who was an ardent devotee of my father’s musicality and had asked him to score music for his operas, asked me ‘Why do you piggy-back on your father’s technique, it’s time you sprinkled some flavour of your own to be ‘Balakrishna the vainika?’

It woke me up from my unconscious shadowing and I willfully tried my solo-presentations with a lot more features added in. In fact, despite his reservations, it was my father’s idea in 1990 that I buy a good German or American contact-mike for my veena to flow with modern requirements.

Your academic research studies in music and lec-dems are also getting popular…

Balakrishna: As raga and laya interests me equally and my listen-and-absorb faculty is sharp, I could take to academics in-depth for lecture-demonstrations.

One of my research study includes the evolution of pallavis as presented by vidwans with élan starting from Veena Seshanna, Mysore Vasudevacharya, Semmangudi Srinisava Iyer, Alathur Brothers amongst others, to the magnum opus of TR Subramaniam.

This is my tribute to their knowledge and diversity of presentation.

As the Conference president of Gayana Samaja’s proceedings this year, I have brought in a special focus to new instruments being constructed by young musicians in the academic sessions.

And as a trustee of Pu Ti Narasimhachar’s Trust for two decades I have taken up the mantle to popularise the playwright’s penchant for classical idioms; and I have created a veena learning-syllabus that any music university or research-students wanting to delve into the Mysore styling can use as a ready-reckoner.

I have been adding my bit to the oceanic reserve. I am thankful to all the honours bestowed on me as Sangeeta Kalaratna, and earlier Ganakalashree by Ganakala Parishat and the Karnataka Kalashri by the Karnataka Sangeeta Nritya Academy.

(Gayana Samaja’s Music Conference - 9 -16 October - KR Road, Bangalore; Balakrishna’s concert on veena with Vamshidhar on flute - 13 October, 6pm; lec-dem on raga-based compositions in Pu Ti Na’s works - 10 October, 10am; Sangeetha Kalaratna award function - 16 October, 10-30am)

Also Read: When Mysore Dasara Festival Echoed The Notes Of Balamuralikrishna