Culture

Jeyamohan On The Question Of Being A 'Cultural Hindu'

Jeyamohan

Jul 19, 2015, 02:34 AM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 10:11 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Tamil writer Jeyamohan’s mail exchange with a reader who wanted to know if one could be a ‘cultural Hindu’ and what that meant. Jeyamohan traces the history of Hindusim through the colonial era and explains how the term came about.

Dear Jeyamohan,

I read that the Turkish writer and Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk calls himself a ‘Cultural Muslim’. That is, someone who does not necessarily follow the rules of Islam, but continues to maintains his cultural and historical connection with it. There seems to be an equivalent term for Christians as well. But I’ve never heard the term ‘Cultural Hindu’ being used.

Despite my family background of deep religiosity, I have never been much of a practicing Hindu. I do not avoid going to temples or applying the Sacred Ash but my rational brain is always on the alert to seek those false comforts. I have never thrust my thoughts on believers, and I do see that there is a place for Hindu faith beyond mere mental comfort.

I wouldn’t go so far as to identify myself as an Atheist, probably because I am worried about cutting myself off from the tradition. I am afraid that the egotistic side of such an identity will land me in a cultural hell without any connection to the tradition that nurtured great art, literature, temples and sculpture and music over thousands of years.

Whether we like them or not, our society makes us wear religious and caste labels,. I’m just trying to stay clear of false identities, be it ‘Atheist’ or ‘Hindu’.

I think ‘Cultural Hindu’ is a good label for people like me to adopt, but I am also confused. What do you think?

Sivendran

—

Dear Sivendran

This is an extremely good question. Indeed, such introspection is becoming rare these days. But before I share my thoughts, I will just ask you to keep in mind that whatever I say should be considered as just one side of the discussion. As you continue your search and form your own ideas, just consider my viewpoint as one possible angle – that is all.

We don’t need to go as far out as Orhan Pamuk to get to the term Cultural Hindu. Its equivalent terms and ideas gained currency in India as early as the ‘Hindu Renaissance’ period in the 18th century.

First, let us look at the historical background on the mindset prevalent at that era. During those times, the Upper-class educated Indians who were mingling with the British were getting uncomfortable with their Hindu identity. They could neither hold onto it nor shed it off fully.

During that time, Hindu customs and its way of life were subject to constant criticism and ridicule from the white rulers. Christian preaching and conversions hit their highs. The educated Hindus grew up being subjected to such pervasive criticisms in their schools.

We can note these dynamics from the biographies from that period – the Hindus tried to bracket such criticism as ‘religious preaching’ and tried to deflect it with available counter-examples of Christian inquisitions and ethnic cleansing in South America and Australia. But they could not take on the hefty questions posed by modern European liberalism and rationalism.

It was also true that the educated Hindus worshipped and admired modern Europe and its intellectual heroes. They invested effort in learning modern European thought but had only a passing understanding of Hindu philosophy. The Hinduism that they saw for themselves was a collection of quaint foolish beliefs and inhuman practices. No wonder they felt so much discomfort in front of the Europeans.

Even the educated British resorted to depicting Indians as steeped in regressive practices and superstition. They characterized the Hindu religion using terms like Totemism, Animism, Pantheism, Polytheism, Shamanism, Idolatry and many other half-baked concepts that were familiar to them. [That practice continues to this day. Our so-called Indian intellectuals still use such borrowed terms to try to understand their own ancestral religion!].

These educated Hindus wanted to move away from such a backward identity. They had a need to portray themselves as modern humanists with democratic outlook and liberal values to the Europeans,. So they got down to splitting Hinduism into two types. They rejected the supposedly old, foolish and backward Hinduism, and tried to create another more modern one without such trappings.

Those were also the times when the Hindu books and scriptures were getting translated into European languages. Behind these lay the immense effort of a few European scholars who sincerely tried to understand Hinduism. When these translations became famous in certain circles in Europe, they got retranslated into English which were then read by the educated Indians of that time. They, in turn, tried to use these as the core philosophy of their neo-Hinduism.

This was the mindset that gave rise to the Hindu Reform movements. The Brahmo Samaj was a good example. It was an attempt to take the Hindu philosophical core and build a ‘Christian’ shell on top of it. Brahmo Samaj sought to create a Hinduism that was close to the modern European worldview.

Brahmo Samaj became popular among the upper-classes of Calcutta. It became understood that the Samaj was a good way to get close to the Whites. The Brahmo Samajis strongly rejected the Hindu ways of temple worship, festivals or sanyasa. Young Hindus with English skills showed a lot of interest in joining the Samaj.

The Bengali parents of those days worried that their youngsters were going to join the Samaj. (The Tamil poet Bharathiyar had based one of his stories – Aaril Oru Pangu – on such a situation).

It was true that organizations like the Brahmo Samaj helped in removing many superstitions and outlawing wrong practices that had all become part of Hinduism. But it also gave rise to a widespread question of whether the Brahmp Samaj was destroying the unique characteristics that made up Hinduism itself. This gave rise to a reactionary trend against the Samaj characterized by deep worship of backward ideas and Hindu conservatism. We can see all these narrated in Tagore’s novel ‘Gora’.

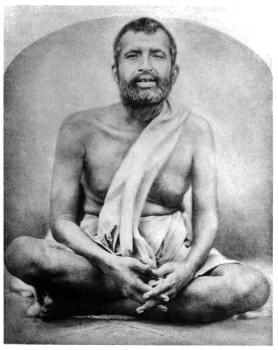

Then, there came a man whose genius and spiritual strength alone took on the Brahmo Samaj single-handedly, and made it disappear – Ramakrishna Paramhamsa!

Ramakrishna took as his students the same enthusiastic educated young men that the Brahmo Samaj had created. The gem among them was Swami Vivekananda. He was a Vedantin who spoke in the language of Brahmo Samaj. The Samaj vehemently opposed Vivekananda – it is very well known that its spokesman named Majumdar worked hard in America to create a slander campaign against the Swami. Vivekananda rose against all this and successfully established that the Hindu Gnana and culture did not reside within its backward customs and beliefs. He showed that Hinduism could stand on its own on the modern world stage, without losing any of its core.

During Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s time, there were many discussions and efforts around separating ‘Hindu culture’ from the ‘Hindu religion’. The most important question then was whether someone could still be a Hindu despite rejecting all its religious customs. The novel ‘Gora’ could be read as a starting point on this topic.

Then we encounter the same question in Jawaharlal Nehru’s works. In fact, if memory serves me right, I have even read the words ‘Cultural Hindu’ in Nehru’s writing.

Nehru was a self-proclaimed atheist. His atheism was based on European liberalism, he felt close to the anti-religious movements that held sway in Europe then. Bertrand Russel’s writing influenced him a lot. He was also very interested in European Naturalist thought.

But Nehru always felt himself a part of Indian culture. He was emotionally connected to Indian philosophy, aesthetics and emotions. He knew that they were all based on Hindu tradition, and he realized that he could not reject them fully.

That’s how he reached the identity of Cultural Hindu. That is, keeping oneself as the inheritor of all the good stuff in Hinduism that developed over thousands of years, and simultaneously, fully distancing oneself from the ‘bad’ parts like God, Temple worship and ritualistic beliefs.

Many of the important intellectuals of the Nehruvian era too identified themselves that way. The literary critic Ka.Na.Subramaniam called himself ‘just culturally a Hindu’. In fact, I heard that term for the first time at a meeting in Chennai when Ka.Na.Su used it on stage.

Like Ka.Na.Su, Sundara Ramasamy too called himself ‘a Hindu on just cultural terms’, he never had any belief in god or interest in religion as far as I knew. P.K Balakrishnan calls himself a Cultural Hindu in his essay. In the bigger Indian scene, one could quote many examples like Dr. Shivaram Karanth and U.R.Ananthamurthy. Even today, many intellectuals prefer to hold this identity.

In Tamil, Jayakanthan was one who strongly argued that the word ‘Hindu’ should be used strictly in a cultural context. He has thundered on stage that ‘I am an Atheist but I am a Hindu’. Jayakanthan has discussed and explained the term Cultural Hindu in many angles.

So the concept itself is not new, it is at least a hundred years old now. It is a concept that was born during the Indian Renaissance period, evolved over time and is still in use today. So we need to understand – what makes it useful today, where does it fit in?

Where did the need arise for Brahmo Samaj to split Hinduism into two? The Europe of that time had created a Hinduism according its own view. For them, Hinduism meant a single religion that was comprised of many things like worship of many gods, idol worship, casteism, untouchability, sacrificial rituals, festivals, superstitions, various kinds of mutts and religious orders, and a strong god-fearing Bhakti.

The only religions that Europeans knew of till then had a monolithic architecture – they had a defined flow and a concrete point-of-view. The Europeans visualized Hinduism in the same way.

When the Europeans started to examine it closely in the 18th century, Hinduism was still pluralistic and malleable. It was when the English-educated Hindus started absorbing the idea of Singular Hinduism from the Europeans that the Hindu religion as we know it today was born.

As far as most Europeans were concerned, all parts of Hinduism were all pieces of one big structure, they operated together. It went like this — Vedanta philosophy and Sati rituals were aspects of the same religion, they were connected. So, if Sati was barbaric then Vedanta too should be barbaric. Rituals like Sati were established and held in place by core philosophies like Vedanta. So Hinduism should be rejected.

It was no surprise that the Conservatives in the Hindu Orthodoxy lapped up this ‘singularizing’ eagerly, it allowed their orthodoxy to claim religious power. But what is puzzling is that this concept was also accepted by the Anti-Hindu atheists. The truth is this: the two opposing groups of Hinduism, the Orthodox conservatives and their radical atheist opponents, have both adopted a vision of Hinduism that was fed to them by the Europeans.

The Hindu conservatives will always argue that all Hindu tradition was Vedic tradition. Then they will say that the Vedic tradition is Vedanta itself, and that the Vedanta underlies all the practices of Vedic tradition. They will call all practices, including Untouchability, as an integral part of Hinduism, subsuming Vedanta within itself. That is, they will reject all the internal dynamics of Hinduism and proffer a singular structure that is advantageous to themselves. They will call that structure as ‘the Hinduism as drawn up by the ancestors’.

The enemies of Hinduism will the echo the same thing perfectly. For them too, the Vedic tradition is the Hindu religion. All its practices are inseparable from Hinduism and Vedanta is just a part of it. There are no differences or conflicts between its practices, philosophies and spiritualities. Just one and the same! It’s no surprise why our atheists love their opponents to adopt such a singular position – they could argue against it easily.

But unlike the European constructed view, the true Hindu way is not monolithic or singular in structure. It is an immense collection of various kinds of philosophies that have enriched and grown each other through mutual discussion and argument. Plurality is its identity, it has no central place for any single philosophy. Its fundamentals are not based on customs, rituals or beliefs. It is a Knowledge Space that progresses on its own internal dialectic that splits and splices, accepts and rejects constantly.

A few people who followed the Marxist approach understood this unique dynamic – K.Damodaran being a good example. E.M.S Namboothiripad also understood it to some extent. For them, the concept of Dialectics was very useful in helping them grasp the idea.

Unfortunately, there is no one in Tamil Nadu today who has understood the Marxian principle of historical analysis. It has devolved into a mere political slogan –instead the Tamil Marxists have only learnt the bad habits from third-rate Dravidian party polemics.

The Hindu Tradition of Knowledge – ‘Gnana Marabu’ – refers to that entire platform of discussion. Vedanta, and its later, more mature forms like Advaita, make up one of the biggest sides of the argument. They are the peaks of Hindu philosophical thought. They are neither dependent nor based on customs, rituals, practices or beliefs. Vedanta can stand on its own as a philosophy without the help of any single religious sect.

Once this concept was firmly established in modern Indian thought by Vivekananda, the proponents of Monolithic Hinduism started to retreat. The idea, that it is not necessary to rely on ‘external intellectual structures’ in order to reform Hinduism, became much stronger. That kind of structure has always been present inside Hinduism itself. It also became clearer that Hinduism has always had space for such kind of self-opposing and self-reforming flows. Thus the Brahmo Samaj finally withered away.

The pluralism stood up by Vivekananda was much strengthened by Narayana Guru’s movement. It too set forth Vedanta as the philosophy of choice, but it used Vedanta as the mighty force against all the backward aspects like Untouchability.

We can see that the traditional opponents of Hinduism are powerless against such a pluralistic vision of Hinduism. That is why they will resort to branding the Pluralist as yet another member of the Conservative camp. They will seek to deploy the same weapons that they successfully used against the Orthodoxy.

Let us say, if someone calls himself a Hindu and a Vedantin. From his ground, he rejects all the orthodox customs and beliefs of Hinduism. What would the enemies do? After all, their regular tactics do not seem to work against him! So they will call him a fraud, an Orthodox wolf in the Progressive sheep’s clothing. Even if he spends his entire lifetime in public working against casteism, superstition and inhumanity, they will denounce him as casteist, backward and regressive. One could quote many examples – Narayana Guru himself went through this.

Now, let me come back to your question. So you are trying to adopt the label of Cultural Hindu – but why? The answer is this – you have sub-consciously accepted the monolithic vision of Hinduism that has been propagated by both the Hindu Conservative and Anti-Hindu camps. You feel that being just a Hindu means accepting all of its customs and beliefs, including foolish inhuman ones.

But you are not prepared to accept it – because your humanism and your logical brain refuses to accept it. So you try to extract only the cultural aspects of Hinduism for yourself. You try to create a place for yourself using whatever you have taken.

But this issue would have never arisen if you hadn’t accepted the European vision of singular Hinduism in the first place. Hinduism is a massive platform of interacting ideas, a cultural space. You are free to take any side, free to join any part of the discussion. Yet whatever you do, you remain a Hindu.

Hinduism allows space for total atheism and total anti-ritualism to exist – within itself. That is, whatever it is that you are seeking to achieve by going outside, there is a place for doing that within Hinduism itself. You could be a Cultural Hindu while fully being inside Hinduism.

You can continue to be a Hindu even if you do not read a single religious book, do not follow any religious sect, do not follow any methods of worship or believe in any god. All you need to do is to find a place for yourself on this great platform. There are many hundreds of good examples. Ramalinga Vallalar is a great example. Wasn’t he a Hindu? Wasn’t his concept of Jyoti worship firmly rejecting of every single philosophy that existed before it?

So why does Orhan Pamuk need to call himself a ‘Cultural Muslim’? Prophetic religions are tight, they do not permit such space. Islam has strict boundaries, those within it must accept Allah, Mohammad and the Quran – else they are not Muslims. If someone realizes that they are unable to submit fully to the faith, yet wants to remain connected to fifteen hundred years of cultural evolution, then the only option available to them is to call themselves a Cultural Muslim.

Does a Hindu face any such compulsions at all?

Forget the whole Hindu identity, let us just take Shaivism. Even Shaivism is a collection of concepts, not a single organized religion. Just look at the sheer number of ways in which Shiva is worshipped!! There are those who read the Thiruvilayadal Purana and worship the Linga daily, and then there are those who sit in meditation saying Shivoham (‘Shivam Aham’ – I am Shiva). Two diametrically opposite points of view! Shaivism has six internal religious sects within it – Shaivam, Pashupata, Mavirata, Kalamuka, Vama, and Vairava. Six Shivas!!

Shaivism can be segmented into three on historical basis.

– One, the Shaiva way of worship, comprised of ancient methods like Linga worship – it is one of the oldest religions in the world.

– Two, the Shaivite religion. It formed around the 4th century BC, and grew by pulling in many forms of Shiva and other gods. Bhakti holds the central place in its worship. All the great Shaiva works of literature, arts and temples were creations of this religion.

– Saiva Siddhanta came up at a much later stage. One could say that its earliest forms developed around the 10th century. The higher aspects of Saiva Siddhanta philosophy developed still a few hundred years later.

Within Shaivites, the pure Siddhantis are at one end of the spectrum, while the ritualists are at the other end. When practicing the purest form of Saiva Siddhanta, you could reject every single custom and ritual of the average Shaivite. Yes, you could even reject the concept of ‘God’ itself.

For a worshipper, who is Shiva? The Lord of the Universe. The one who creates, conducts and destroys the Earth. You could submit to him, worship him and achieve a good life and contentment.

But who is Shiva for a Siddhanti? In his view, the knowable Universe is a space of boundless energy. He calls it the Shakti. There is a principle that gives the Shakti the active and creative characteristic. That principle is the Shivam.

The Siddhanti does not need to worship the Shiva, he does not need to submit or pray, and he does not need to give it any form. He just needs to feel Shiva’s cosmic dance in all of the Universe, that’s his state of completeness. That’s his salvation. Now, does religious faith figure in this? This is entirely a high-philosophy discussion. And since it seeks an overall vision, it is Spiritualism. But anyone at this level is still a Shaivite.

You feel that if you identify as a Shaivite, you will feel compelled to put on the Sacred Ash, sing the Devaram hymns, and perform Shiva puja every day. But since you cannot bring yourself to do any of this, you just want to retain the cultural aspects of Shaivism. I’m just bringing all this up just because one of your statements is just the result of not knowing the space available within Shaivism. You could be a purely philosophical Shaivite without doing any of the things that you mentioned.

Okay, but could you also reject Shaivism and take up total Atheism? You would reach the Lokayata religion – which is called by Shaivism as ‘Exterior Religion’ (‘Purachamayam’). There are many aspects within Lokayata too.

We could describe it all this way. Say, there is a big fort; you could build your house outside the fort. The town grows like that. If you build your house outside the town, the town just becomes bigger and now includes your house.

That is, in your current state, you do not really need an identity like Cultural Hindu, there is no need to define yourself that way. The Shaivite religion seems to be your family tradition – but if you are not able to gel with its everyday practices and god forms, you do not need to come out of it and call yourself a Cultural Hindu and all that. There is space within that religion for you to move beyond customary worship and move to higher levels of experience. A Shaivite worshipper becoming a Saiva Siddhanti is equivalent to crossing the distance from the earth to the sky.

If you are still unsatisfied after reaching that pinnacle, if you have learnt every spiritual-philosophical explanation that Hinduism has to offer and have rejected all of them, and then if you fully feel that you are an Atheist but are unsatisfied by all the Charvaka atheist philosophies in Hinduism, then – and only then – you could go outside and call yourself a Cultural Hindu.

But I still think there is a place for the term Cultural Hindu today. Two reasons:

– All the religions that evolved out of India like Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism, could be seen as belonging to the same cultural space. Their mythologies, fundamental beliefs, and symbolisms are all born out of what we would generally term as Hindu Culture.

– If someone is Jain, Buddhist or Sikh, they could be still be called as culturally a Hindu. You could also include Sufism in this. The symbolism and the stories in the songs of Kunangudi Masthan Sahib, Peer Mohammad Appa and Umaruppulavar were all born out of the immense Hindu cultural space.

Here we should use the word Hindu carefully – not to create differences but to remove them. That word does not belong to anyone, it cannot be controlled by anyone. Like the rivers and mountains of this land, it belongs to everyone that was born here. That was a quote from Jayakanthan in one of his speeches.

Secondly, Cultural Hindu will be useful for someone to identify with when they have fully moved away from all Indian philosophies and have adopted a Western mindset, yet does not intend to lose touch with Indian cultural aspects.

However we look at it, it is a useful term. It provides a good response to all the hatred against the word ‘Hindu’ that has been swept up by the religious conversion machinery and their paid servants among the Indian intellectuals.

Obviously, those who call Orhan Pamuk progressive for calling himself a Cultural Muslim will take a step back to think when Siventhiran calls himself a Cultural Hindu, right? Why should we lose that opportunity?!!?

–Jeyamohan

(Translated by: Madhusudhanan Sampath. Photo credit > SiliconShelf)

Jeyamohan is amongst the leading writers and critics of Tamil and Malayalam