Culture

Kaithi Is Key To Unlocking Land Records In Bihar; The Problem Is, Very Few Understand It

Abhishek Kumar

Sep 10, 2024, 07:00 PM | Updated Oct 03, 2024, 11:20 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

.jpg?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

Just like its land digitisation programme, the Bihar government’s latest land survey has met an unusual roadblock.

The officers deployed for the work of streamlining land-related documents are often unable to decipher them.

A near-obsolete script is the reason behind it.

A large chunk of the records in pre-1980 files have been written in the Kaithi script, the readers of which are becoming extinct.

In the majority of Bihar's districts, Kaithi readers are few and far between — often fewer than 10. The younger ones among them are able to read Kaithi but can't decode old documents because they contain a more 'official' or 'classical' version of the script. And most of them have learnt the language through short-term courses run by Kaithi enthusiasts.

Realistically speaking, those in the 75+ years age group who worked as typists in government departments — especially in courts — in their heyday can interpret it.

However, due to the mismatch in demand and supply (again, these people are very few in number), they charge anywhere between Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 per page — steep for the average person in the state, whose per capita income is less than Rs 200 per day.

Where Did Kaithi Come From?

Though its origins are not well-established, Kaithi is believed to be one of the north Indian derivations of the Brahmi script, prevalent during the Gupta dynasty.

There are two conflicting opinions about Kaithi's origin.

One viewpoint is that the script came directly from Brahmi due to the latter’s decline, while the other — endorsed by linguist and administrator George Grierson — is that Kaithi evolved because the Devanagari script required lifting the pen to write letters and draw horizontal and vertical lines and was, therefore, too complex for administrative work.

According to Grierson, there was a need to discard horizontal and vertical lines, and that is how Kaithi ended up becoming one of the derivatives of the Devanagari.

However, this theory doesn’t stand the test of alphabetical similarity — too few Kaithi alphabets are written in the same way as the Devanagari letters.

A simplified language was a requirement of the Kayastha community, who mainly worked as recordkeepers in king’s courts. Their work involved revenue collection, revenue recordkeeping, deed writing, and administrative and general correspondence.

Due to the paucity of time in writing down oral orders, the Kayasthas needed to write more quickly. If only things could be written without lifting up the pen. That is how the Kaithi script rose to prominence.

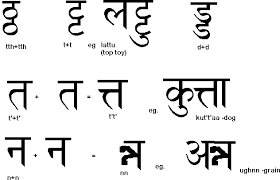

Unique Features Of Kaithi

Kaithi is free of the complications typically associated with the written word.

For instance, Kaithi gives writers the flexibility of distance between two words, which is why its words have evolved to be increasingly curved. It also does away with the use of symbols of vowels and joint letters.

There is also not much emphasis on writing a grammatically correct word.

For instance, English word 'shoe' is translated as जूता in Hindi. But when you write जूता in Kathi script, it can also be written as जुता.

Due to its simplicity, writing in Kaithi saves time. That helped in its mass adoption.

In 1540, Sher Shah Suri officially adopted it in his royal court. He also inscribed the script in the coins used for business transactions in the state. The state endorsement led to increased popularity.

After the Mughals, the British adopted the Kaithi script. In fact, throughout the script's existence, Kaithi's use was closely linked to Bihar, although it prevailed in Uttar Pradesh and Bengal too.

Ramcharitmanas, the epic Tulsidas poem on the Ramayana, was also written in Kaithi. Furthermore, all official work was recorded in Kaithi, and it was taught in schools until Class VII.

Kaithi's Decline

Kaithi's use underwent a change after the Revolt of 1857. Professor Alok Rai, in his 2001 book Hindi Nationalism, says that after the revolt, an elite class was created that focused more on the purity and standardisation of language, as against the raw form of Kaithi.

This class started to put more emphasis on the Devanagari script due to its standard form. To get it accepted, they required backing from Devanagari writers. They sought mass signatures for its use. Rival Kaithi did not have any such movement for preservation.

Dhrub Kumar, a retired psychology professor and writer of the book Kaithi: An Introduction, says that the Nagrik Pracharini Sabha, founded in 1893, played a key role in the decline of the Kaithi script. Kumar says Kaithi’s strength — its simplicity — was projected as its weakness.

The script was ousted from the official list in 1913, but its use in daily life continued for decades. Bhikhari Thakur, arguably the greatest legend of Bhojpuri language, is said to have written all his songs in Kaithi because he had only learned the Kaithi alphabet and the Ramcharitmanas.

Attempts At Revival

Kaithi's use also continued because of its mass adoption in multiple languages. It was used to write Hindi, Bhojpuri, Magadhi, Angika, Vajjika, Maithili, Awadhi, Bengali, Marwari, and even Urdu. In land records, a few officers kept using it until the early 1990s.

As of today, Kaithi is not widely used, but considering its relevance to some of the most contentious land issues in Bihar, the state government is making the effort to revive it.

In 2016, the government organised a crash course at Bhagalpur’s Tilaka Manjhi University, which received 30-40 participants.

In October 2022, the state government announced that it is working on a revival plan, but details are yet to be released two years hence.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.