Culture

Magh Bihu: More Than A Feast, A Stand For Local Meat Traditions Against Halal Hegemony

Nabaarun Barooah

Jan 13, 2025, 03:07 PM | Updated Feb 01, 2025, 02:29 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

(Reader discretion is advised: This article contains images of meat markets.)

In the heart of Assam, a festival stands as a testament to the region’s rich agricultural traditions and culinary diversity.

Celebrated with immense fervour and enthusiasm, Magh Bihu, also known as Bhogali Bihu, is a harvest festival that marks the end of winter and the culmination of the rice harvest.

It falls in mid-January, coinciding with the end of the month of Pooh or Pausha in the Hindu lunar calendar, and is a celebration of a successful harvest, as nature is thanked for its bounty.

It turns into a vibrant display of community spirit, feasting, and a celebration of indigenous food traditions.

Beneath the lively festivities, however, Magh Bihu serves as a subtle but powerful form of resistance against the silent hegemony of the halal meat economy that has grown dominant in the modern food market.

I am not against halal meat. In a democratic country like ours, every individual and community has the right to choose what they want to consume. However, I am against the uniform imposition of one particular choice of consumption, as it disregards culinary diversity and infringes upon one’s right to choice.

Halal meat, governed by Islamic dietary laws, has been promoted by large-scale meat producers, international food chains, and even government-operated tourist restaurants and agencies.

Fast-food giants like McDonald's, KFC, and Burger King, along with erstwhile national carriers like Air India, have increasingly adopted halal meat as their primary choice, catering to the preferences of a particular community, leaving little room for diversity.

Halal meat has become the default option in many urban areas, including in Assam’s larger towns and cities. This shift has posed challenges for indigenous butcher communities. Their businesses, often passed down through generations, face competition from halal markets that enjoy significant institutional backing.

This change, while catering to a specific market, has inadvertently marginalised indigenous non-Muslim butcher communities, many of whom rely on the sale of meat for their livelihoods.

The imposition of halal meat in public spaces has disincentivised local non-Muslim butchers from entering the meat market, as they find it increasingly difficult to compete with the monopolistic tendencies of the halal industry.

For example, while halal meat sellers have permanent places allocated to them in markets, many non-halal meat sellers have to contend with makeshift stalls.

The Bihu eve, or Uruka, is integral to Magh Bihu festivities. The word “Uruka” is derived from the Deori-Chutia word “Uru-kuwa,” meaning ‘to end.’ It symbolises the conclusion of the harvest season and the final day of the month.

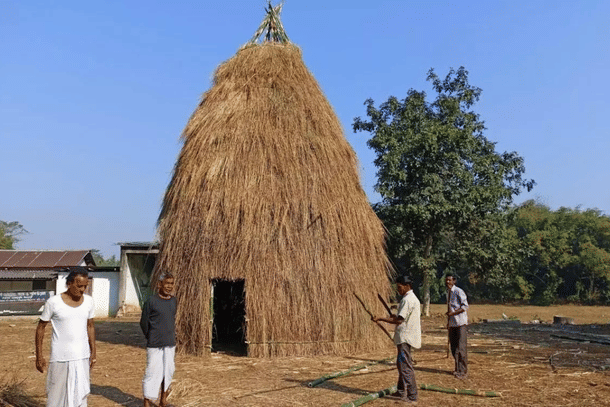

On this night, villagers come together to build makeshift straw huts known as Bhelaghars, where they prepare an array of traditional dishes and indulge in a community feast that extends well into the night. Villagers prepare pithas, or rice cakes, sticky rice, and a variety of fish and meat dishes.

While the celebration is marked by a bounty of grains, fruits, and vegetables, it is meat that plays a central role in the festival.

Meat from locally reared animals — chicken, pork, mutton, duck, and fish — is cooked in myriad traditional styles.

The local meat economy experiences a significant boom as a result. Local butchers, especially from indigenous communities, profit from the surge in demand for meat during Uruka night, marking a seasonal high point for their trade.

Local butcher communities, predominantly from the Scheduled Castes and the Koch-Rajbongshi, Bodo, and Ahom communities, and fishermen communities, predominantly the Kaibarta community, engage in the slaughter and sale of various types of meat and fish.

These butcher communities have long been involved in the local food supply chain, ensuring that the people of Assam have access to a wide variety of meats.

Against the backdrop of growing halal dominance, Magh Bihu gives these local butcher communities an opportunity to reclaim their space in the meat economy.

By participating in these communal meat preparations, local butchers not only strengthen their ties with the community but also assert their culinary traditions and business interests.

Duck and pork, for example, are integral to the cuisine of Assam. Dishes like duck curry with ash gourd, smoked pork, and bamboo-shoot pork, served with local alcohol, are staples at communal feasts.

Unlike the widespread dominance of halal meat in the chicken and mutton industries, the duck and pork markets in Assam remain firmly in the hands of indigenous and tribal communities, such as the Ahoms.

These communities have a long-standing tradition of raising ducks and pigs, and, as the demand for these meats grows, they are uniquely positioned to capture the bulk of the sales.

This control over the duck and pork industries has reinforced the economic position of these communities, ensuring that they continue to play a central role in the local food supply chain.

By tapping into this expanding market, tribal farmers and butchers are able to maintain stable, year-round operations, running thriving piggeries and duck farms.

So, indigenous communities not only benefit economically from the booming demand but also find themselves playing a vital role in preserving Assam’s culinary heritage.

The support from Assamese society creates a symbiotic relationship, where local meat producers are able to thrive while contributing to the region's rich food culture.

The demand for pork and duck has also led to the expansion of farming practices. Tribal farmers, with their knowledge of sustainable animal husbandry, have been able to scale up their operations to meet the needs of a growing urban market and break the monopoly of the halal industry.

The availability of affordable, high-quality meat has enabled them to tap into new consumer segments, including those from other parts of India, who are seeking authentic, traditional meats.

A local entrepreneur, who works in the piggery sector, mentioned how exports to Tier-I cities like Delhi and Mumbai have increased manifold in the past few years.

The festival serves as an annual reminder of the importance of indigenous meat industries. It offers them a window of opportunity to thrive in a market dominated by global chains and standardisation.

Magh Bihu, thus, is a time when Assamese society comes together to celebrate their shared cultural heritage, but also, in doing so, help sustain traditional industries that might otherwise be overshadowed by the forces of globalisation.

While it may not be a conscious rebellion against halal imposition, Magh Bihu stands as a silent revolution — a celebration of the right to choose, the right to preserve culinary traditions, and the right to support local economies.

Nabaarun Barooah is an author and commentator.