Culture

Navratri Notes: Inanna, The Goddess Of Life And War

Aravindan Neelakandan

Oct 04, 2024, 06:25 PM | Updated 11:02 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

She was the Goddess of the mountains and the Goddess of the sky. She was the Goddess of war and the Goddess of verdant fields, capable of scorching the land with her wrath.

She was Inanna, the divine force where the heavens and earth converged.

As the cultural and spiritual influence of Sumerian civilization began to radiate across the ancient world, Inanna, the revered Goddess of Sumer, transformed and adapted, becoming a deity embraced by other cultures, each with their unique adaptations which She gracefully and harmoniously internalised.

In the twilight of the third millennium BCE, a new power emerged—the Akkadians. Under the reign of the formidable Sargon, they seized the Sumerian city-states, which was the commencement of a new empire. Amidst this backdrop, Sargon’s daughter, Enheduanna, ascended as the high priestess of Inanna, the revered Goddess of the vanquished Sumerians.

The sands of time buried Enheduanna’s legacy until 1927, when archaeology resurrected her memory.

Western scholars often viewed her role through a political lens, pondering whether her elevation was a strategic effort to forge a syncretic cult, blending Akkadian and Sumerian beliefs to fortify and legitimize Akkadian rule.

As one delves into the exaltations of Inanna—arguably the earliest recorded hymns known to humanity—one encounters more the blossoming spirit of a female mystic than a political strategy for power:

At your battle-cry, my lady, the foreign lands bow low. When humanity comes before you in awed silence at the terrifying radiance and tempest, you grasp the most terrible of all the divine powers. Because of you, the threshold of tears is opened, and people walk along the path of the house of great lamentations. In the van of battle, all is struck down before you. With your strength, my lady, teeth can crush flint. You charge forward like a charging storm.

Great queen of queens, issue of a holy womb for righteous divine powers, greater than your own mother, wise and sage, lady of all the foreign lands, life-force of the teeming people: I will recite your holy song! True goddess fit for divine powers, your splendid utterances are magnificent. Deep-hearted, good woman with a radiant heart, I will enumerate your good divine powers for you!

The hymn exalts the divine essence of the Goddess, her supreme nature resonating through every verse.

She was the great cow among the gods of heaven and earth. The Sumerian Devas, the Annuna, bow low, their lips caressing the earth in reverence before Her.

This chant, a tribute to the Goddess in her battle fury, captures the intensity of Her wrath, which had not yet subsided.

Yet, by the hymn’s end, her rage got soothed, her spirit calmed. ‘The Exaltation of Inanna’ by Enheduanna stands as the first known hymn inscribed with the author’s name, a testament to a woman’s voice echoing through the annals of history.

Her temple was a symbolic mountain - the meeting point of the ascent of humanity and descent of divinity but grounded in the body of the Divine Feminine. This Temple was also Her body. The mountain it symbolised thus was no ordinary mountain.

Historians of feminine religious traditions of the West, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford point out that it 'as in Hindu mythology,... symbolized the primordial cosmic mountain that existed before the creation of earth and heaven.'

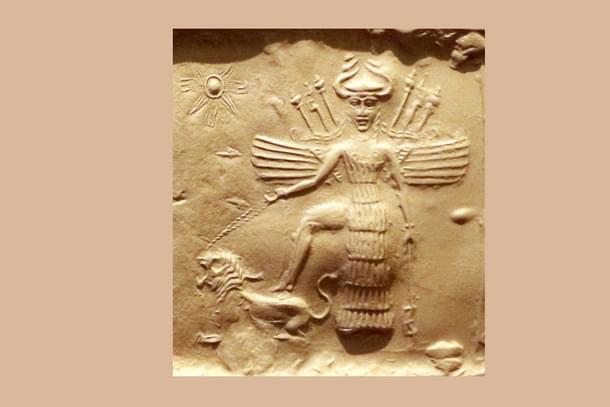

In Sumerian seals She was depicted with a lion under Her feet. She was also the sacred cow of the heavens.

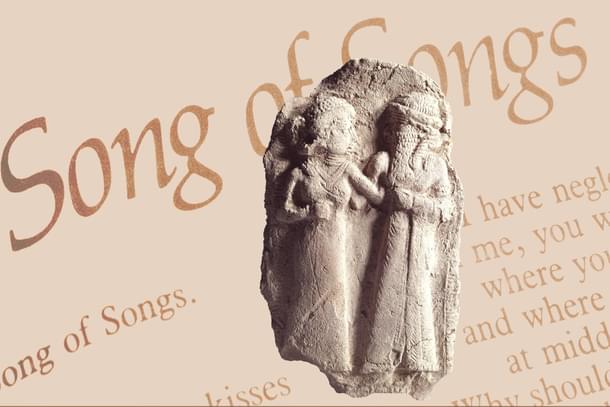

The Goddess was hailed as the tamer of beasts. She had a consort whom She had chosen. He was a shepherd-fisherman named Dumuzi (Tammuz in Akkadian). The marriage became the sacred marriage of the Goddess with Her husband. The bridal mysticism shines through the hymns praising and describing this divine marriage. They would later influence and shape bridal mysticism found in Western tradition through the Song of Songs of Hebrew Bible.

Subsequently the mythological tradition which dramatically involves death and resurrection cycle became the most dominant tradition in Sumer. Inanna the Goddess of life descends into the realm of death governed by Her feminine opposite Ereshkigal, a Goddess of death. David Adam Lemmings, an authority in world mythology, explains:

The myth of the hero's descent to the underworld is found in most cultures. The particular myth of Inanna's descent and the sacrifice of Dumuzi, which is associated with it, adds the element of resurrection that links it in varying degrees to such stories as those of the Greek Persephone, the Egyptian Isis and Osiris and the Christian Jesus. And these stories and others like them have in common the celebration of physical or spiritual fertility related to a ritual journey to the depths, where shamanic powers are experienced or gained. There is also in Inanna's descent an implicit agricultural element involving 'planting' under the earth and ultimately productive decomposition. The Inanna descent myth tells how as 'Queen of the Above', Inanna, always in search of knowledge, longs to know the Below of her sister Ereshkigal, the negative opposite aspect of the ripe goddess of love.David Leeming, The Oxford companion to world mythology, 2005, p.196

In the West, the evolution of the Goddess tradition was stifled by the rise of monopolistic religions. Yet, even within these confines, She endured, marginalised and veiled in symbols. When the myth of Jesus’ resurrection emerged, the Goddess was either absent or relegated to the margins, embodied in Mary Magdalene, the witness.

An Inanna or a Nammu need not have an Indian origin. But they with all their glory still live in Indian Goddesses.

The sacred chants of Inanna no longer echo in the places where She once manifested. The call to prayer for a singular god has silenced Her hymns. Enheduanna gazes around in sorrow.

Then, she hears the chant. The chant from the East— chant of a Goddess through Rishika Vaak, the daughter of rishi Ambhrina:

I am Rashtri the embodiment of Nation, the gatherer of vasus (treasures), knower of Brahman, the Primary One in the object of yagna. The gods have dispersed me in many places, having many abodes, causing me to pervade (or overpower) many

In the majestic mystic lines of the sukta, Enheduanna realises the imperishable Inanna within.

As fanatic hordes bring down the Durga Puja pandals in Bangladesh, Enheduanna joins Vaagaambhrini:

aham rudraya dhanur a tanomi brahmdvise sarave hantava u

aham janaya samadam krnomy aham dyavaprthivi aa vivesa

Also read: Navratri notes: Nammu, the forgotten Serpent-Sea Goddess from Sumeria