Culture

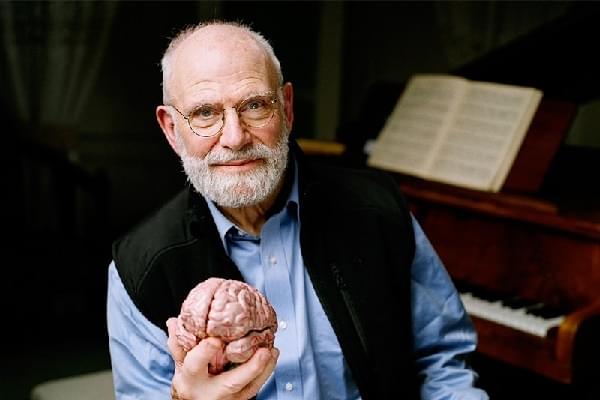

Obituary: Oliver Sacks (1933 – 2015)

Aravindan Neelakandan

Sep 01, 2015, 06:12 PM | Updated Feb 24, 2016, 04:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Oliver Sacks, best selling author and neurologist, helped make human self-perception so much more profound.

According to his Twitter handle, Oliver Sacks spent his final days doing what he loved—playing piano, writing to friends, swimming, and enjoying smoked salmon. When he learnt that he would die within a few months due to liver cancer Sacks wrote that, though there was fear, the dominant feeling was one of ‘gratitude’.

He had been a survivor of ocular melanoma, a rare eye tumor, for almost a decade and at 81 could still swim a mile daily. The writer of the ‘quirks of brain’ was as aware of the internal changes that took place in him as ever – even as he faced that one imminent biological certainty from which we cannot escape. He put his feelings in a small essay that appeared in New York Times (Feb-19, 2015):

“Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

He always did that exceptional thing called self-observation. For example, when he was writing ‘An Anthropologist on Mars’ he had a surgery in his right shoulder and hence was compelled to write with his left hand. He discovered that he was becoming ‘very adept, prehensile…’. He observed that he had ‘discovered a new balance… developing different patterns, different habits… a different identity…’. He speculated that ‘there must be changes going on with some of the programs and circuits’ in his brain which should be ‘altering synoptic weights and connectivities and signals…’.

Oliver Sacks had his share of criticisms as well. His much-quoted instance of autistic-psychotic twins with exceptional mathematical abilities came for some criticism. Narrated in his most popular book ‘The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat’ the things that Oliver Sacks records are indeed amazing:

A box of matches on their table fell, and discharged its contents on the floor: ‘111,’ they both cried simultaneously; and then, in a murmur, John said ’37’. Michael repeated this, John said it a third time and stopped. I counted the matches – it took me some time – and there were 111.

‘How could you count the matches so quickly?’ I asked. ‘We didn’t count,’ they said. ‘We saw the 111.’

…

‘And why did you murmur ’37’, and repeat it three times?’ I asked the twins. They said in unison, ’37, 37, 37, 111′.

For explorers of consciousness like Subhash Kak, the mathematical savant example provides a window to look into the way consciousness works: “The abilities of these savants and of mnemonists cannot be understood in the framework of a monolithic mind.”

Though Sacks considered David Hume his favorite philosopher, he never fell into the trap of the idealism-materialism binary. Nor did he fall for either neuronal reductionism or the orthodoxy of establishment. It led him into unchartered territories and made human self-perception more profound.

Perhaps his book ‘Musicophilia’ is one of the most beautiful poetries of the narrative he had ever woven through his writings. He started by pointing out Darwin’s own perception of the production and enjoyment of music as ‘the most mysterious’ of the human abilities, because they are of ‘the least use to men’. Then he quoted Steven Pinker who considered music along with all arts as having ‘no adaptive function at all’.

And then he wrote:

Yet regardless of all this – the extent to which human musical powers and susceptibilities are hardwired or are a by-product of other powers and proclivities – music remains fundamental and central in every culture. We humans are a musical species no less than a linguistic one.

‘Listening to music is not just auditory or emotional it is motoric as well’ he wrote quoting Nietzsche to that effect, and then declared: ‘Our auditory systems, our nervous systems are indeed exquisitely tuned for music.’

A lesser science writer would be tempted to show his audience how he had ‘deconstructed’ music into its neural components and perhaps even provided a Darwinian context but not Sacks. He then spoke humbly of the multi-dimensional matrix like the web in which the phenomenon emerges:

How much this is due to the intrinsic characteristics of music itself – its complex sonic patterns woven in time, its logic, its momentum, its unbreakable sequences, its insistent rhythms and repetitions, the mysterious way in which it embodies emotions and “will” – and how much to special resonances, synchronizations, oscillations, mutual excitations, or feedbacks in the immensely complex, multilevel neural circuitry that underlies music perception and replay, we do not yet know.

An Indian mind would exclaim ‘Pratītyasamutpāda’ reading Oliver Sacks.

Today his music has merged back with the existence of which it has always been an inseparable part, and the planet has become a bit more beautiful because it was sung.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.