Culture

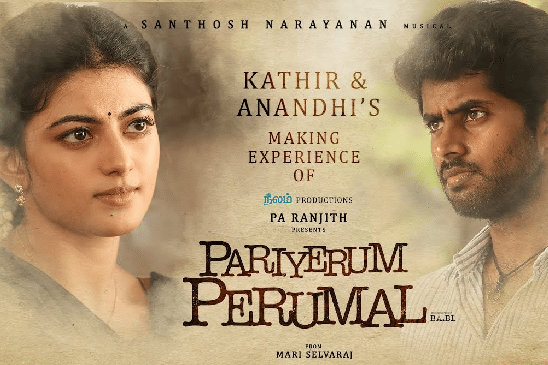

Pariyerum Perumal: A Tight Slap On Over 50 Years Of Dravidian Rule

MR Subramani

Oct 20, 2018, 05:21 PM | Updated 05:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Fifty-one years ago, Dravidian parties led by the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam took over the reins of the government of Tamil Nadu. The rationalists that they claimed to be, were supposed to ensure equal treatment of all Tamils to end casteism and untouchability.

But isn’t it a fact that even today, the two-tumbler system pervades in some parts of the state, especially in the southern parts? The Dravidian parties rode on anti-Brahminism, blaming an upper caste for the ills of the state. It has been long since that forward community in question was sidelined, yet casteism and untouchability continue. Ironically, these ills of the society are being promoted by communities that are termed by law as the Most Backward Classes (MBC) against the Scheduled Castes (SC).

Released without much fanfare, Pariyerum Perumal (pari means horse and erum means mount) is a tight slap on all these years of Dravidian rule. The hero of the film, Pariyerum Perumal, has been drawing rave reviews for laying bare the truth that is prevalent in Tamil Nadu today.

The film’s opening scene portrays the inhuman treatment the animals owned by SC community are subject to, but towards the climax, the movie seems to establish that the downtrodden themselves are treated as animals or even worse even, today.

Lead actor Pari or Pariyerum Perumal tries to dodge trouble and concentrate on becoming a lawyer. In his efforts to progress in life, he even gives those suspected of killing his pet animal the go-by. But some members of the Other Backward Class or the Most Backward Class (MBC), identified from the place his classmate (the heroine) comes from, wouldn’t let him live peacefully.

Pari wants to become a lawyer like Dr Ambedkar but his friendship with a classmate lands him in trouble. It’s not love, at least for Pari, but the classmate appears to have special feelings for him.

Director Mari Selvaraj brings to the fore the mindset of the downtrodden with the hero choosing the back bench in his classroom to sit. He has captured well the difficulties of students in the state in comprehending English. In a humour-laced narrative, Pari tells his friend how despite getting 390 marks out of 500, he had failed in the Class X board exams because he didn’t know English, and wasn’t sure how to copy from the ‘bits’ he had taken with him to the exam hall. The film conveys how a majority of college students are ill at ease with English. However, it does not preach on the importance of Tamil or the mother tongue. That is left to the audience’s thoughts.

After being humiliated by his classmate’s relatives, one of who even urinates on him, Pari decides to face the issue head on. He moves from the backbench to the front row only to face more problems. It is a poignant reminder of what certain class or communities think of the downtrodden.

Selvaraj has restricted dialogues that appear preachy to just passing remarks. At the beginning of the film, hero Pari says the marginalised families have little option as long as they are working in the fields belonging to other castes! Cut, the director ends it just there. Or in the climax, which sums up the reality, Pari tells his classmate’s father: “You want to be yourself but you want us to be dogs. Until then, nothing will change!” Is that a message to the rulers of the state?

Selvaraj does things subtly on the silver screen making one wonder if a new form of politics is creeping in, in Tamil Nadu. The camera, a wonderful work, at least twice pans on a wall that shows Ilayaraja Kabaddi Mandram (team) with a caricature of the maestro. It looks that despite the efforts of the Dravidian parties to run down the musician, people in general look up to him.

Then, the director brings up the issue of honour killing with a contract killer targeting the hero. Here again, Selvaraj leaves it to the audience to make their own judgements.

Another instance is of an elderly man who takes up the cause of his people and when he questions a police inspector, he is slapped in return. The director could have spun this into an act of revenge, but he concludes it with a neat dialogue when the old man tells the youth of his caste, and who watch his humiliation to refrain from telling about this incident to the people of the village as he will lose their respect.

The director sends out yet another subtle message when the law college principal tells a professor in support of a Pari in trouble: “Let him take on the forces. Let the others know that they simply can’t have their way.”

Selvaraj doesn’t really delve deeply into religion, something that Dravidians resort to while attacking Hinduism. In fact, for any problem, including the current #metoo campaign against people like Vairamuthu, the Dravidian parties either blame the upper caste or the Bharatiya Janata Party. Many like DMK president M K Stalin have chosen not to respond, albeit selectively.

But in the movie, the heroine is seen writing Sri Rama jeyam praying that Pari clear his arrear exams. The hero only chides her! That’s all. Here, again, there is no preaching or any dialogue.

Later, when the hero is at a government hospital, attending to his injured and insulted father, the heroine comes to meet him and break the good news that he has cleared his arrear exams! Selvaraj and his producer Pa Ranjith, yes the man who made Kabali and Kaala, seem to have been very clear about their objective from the outset. The focus has been on the real issues of the downtrodden or the Scheduled Castes. No mixing of politics, of whatever shade, and religion. The hero drinks only black tea in the movie and the director leaves you to draw your own conclusion, though the effect of it is not lost on the viewer

The hero, his families and friends are seen respecting tradition, yet not a single dialogue on religion or politics to convey this. There is a scene where a slogan is written on a part of the wall that is painted red that denotes communism. If it leaves one with a thought that perhaps we would see something relating to communism, then there is nothing of that sort. Dogs play an important role in this movie and seem to represent the grim caste reality in Tamil Nadu.

Pariyerum Perumal is a film that focuses on the travails of the Scheduled Caste in Tamil Nadu. In bringing those issues to the fore, Selvaraj holds a mirror to the role of the Dravidian parties in particular. Probably, that’s why this movie has met with silence from the Dravidian parties or the usual sponsors of injustice meted out to the oppressed class.