Culture

Past Over Present: Why Karthik Subbaraj’s Cinephile References Weaken His Own Voice

K Balakumar

May 03, 2025, 08:18 PM | Updated 08:18 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

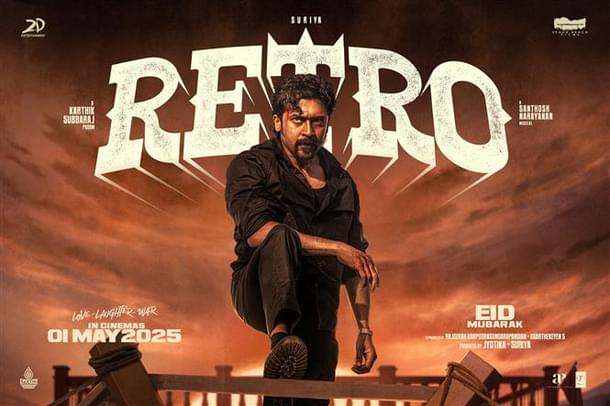

The two Tamil movies that released on May Day, Retro and Tourist Family, have one thing in common: Both dip into the Sri Lankan Tamils issue, which, for all practical purposes, is dead as a mainstream happening in Tamil Nadu.

In Retro, the reference to Lanka is not overt, but we all know that Karthik Subbaraj as a director likes to grapple with the predicament of island Tamils and had done so in his Jagame Thandhiram (2021) and the Netflix anthology Navarasa (2021) in which his episode, named Peace, was based around two LTTE fighters.

In the event, when Retro moves to Andaman islands in the second half with the events centred around a violent group that exploits Tamils and treats them as slaves, it is not impossible to imagine that the director has in his mind the events relating to India's southern neighbour.

Tourist Family, on the other hand, is more direct. It is about a family that illegally arrives from Sri Lanka into Tamil Nadu and its effort to begin life afresh here. Tourist Family embeds the refugee experience directly into its narrative, offering emotional and fun depiction of their survival story here, while Retro takes a more abstract route, weaving displacement and oppression into metaphorical storytelling.

Tourist Family's ambitions are realistic, and it sticks to people and their every-day struggles with a soft-lens gaze. It teeters on the edge of schmaltzy without tilting over as it is saved by the fact that it doesn't take itself or the situation too seriously. Every emotional conflict is resolved through some nifty switch to levity. As it unfolds on screen, it doesn't look like cheating or abrupt, as the changeover matches the larger approach of the film. The denouement in humour is an organic transposition in the context of the film.

Retro bites off more than it can chew

Retro, on the other hand, is more vaunting in its aspirations, but eventually disappointing as it is unable to come up with a narration that matches its needs. The film's second half especially comes unstuck with its bizarre ways. Technically well made, but the content doesn't live up to it because the methods of the maker seem clever by half.

He seems too busy doffing the hat to movies like Gladiator, Django Unchained and trying to fill the narrative with some easter eggs and political messaging that he seems to have forgotten the actual idea of Retro.

Which brings us to the tendency of modern Tamil filmmakers to overdo this engagement with intertextuality — referencing other films, cinematic tropes, pop culture happenings and cultural narratives. In itself, cinematic callback is not a wrong thing to attempt as you build on existing material or ideas to fit your material. Referencing past works allows filmmakers to engage with a shared cultural memory, reinforcing narratives that resonate across generations.

But when that in itself becomes predictable it not only dilutes the thematic impact of your material, but also pulps it to a cliché. That is what happens with films like Retro.

In Tourist Family too there is a small stretch when a famous 'kuthu' song from a yesteryear movie is invoked. But since that OG song was famously picturised on Simran, and here too it is Simran who recreating the same, and it becomes an enjoyable, harmless fun, and more importantly, it doesn't alter the flow or the mood of the movie.

Ditto with a scene involving a really heated and extreme exchange between the father and son, but the finality of the scene is reached through a song (and performance) that is hugely popular among Instagram wedding reels-makers. Every crisis of the moment on the screen is averted through such fun or light-hearted twists or tweaks. So this cheeky approach fits snugly into the larger mood of the movie.

This is where Retro falters. It struggles to balance its political undertones with its stylized storytelling and intertextual echoes or thematic parallels. When the Senorita song from Johnny (1980) is used here it feels less interesting or enjoyable and becomes a mere marketing gimmick to tap into the audience's warmth for nostalgia.

Substance subservient to style

Retro also attempts to weave allegorical references to displacement and exile but leans heavily on cinematic tropes rather than crafting a fresh perspective. The referencing feels more like an intellectual exercise than an organic storytelling choice. In the event, the film loses its emotional focus. You hardly connect with the characters or their issues thereof. Everything seems in service of style rather than substance.

And that bane of Tamil cinema, the gangster theme, is also Retro's undoing. Karthik Subbaraj's body of work is filled with this idea. But in most of them, he brought some novel, outré perspective, but here he is heavy-footed and stuck on older riffs.

Retro also overplays the Lord Krishna and the 'chosen one saviour' parallel almost literally. Creators reinterpreting Hindu religious stories and epics is nothing new. Mani Ratnam in recent times is a major example. And even his attempts in Thalapathi (a retelling of Karna story with modern idioms), Ravanan (Lord Ram, Sita and his arch rival story), Chekka Sivantha Vanam (a slice from Mahabharata with father and sons conflict) have at best been middling.

Karthik Subbaraj doesn't have the gravitas to pull off a part of Lord Krishna story as Retro. So the references are literal and hence lack subtlety. The Krishna-like hero is brought up by another woman (Yashoda reference box ticked), his lover is named Rukmini (Rukmini reference box ticked), the people see him as the only one who can kill the evil forces but he himself is morally ambiguous (Krishna box ticked). The film also tries to pit Krishna's path of practical action and Buddha's way of peace and make an ideological debate of sorts.

With thoughts crowded with ideas, the director is unable to provide the narration an even flow. The latter half with so much stuffing feels more like a cinematic puzzle than a cohesive story.

When nostalgia becomes more about reverence than reinvention

As said, intertextuality can be a creative tool when used to subvert expectations or add layers to a story. However, when it is not done adroitly it signals a lack of original ideas. And this seems to be a pandemic in Tamil cinema. Almost every second movie released has a scene or two referencing popular movies of the past and most certainly a song or two from then.

Retro is only the latest manifestation of this malaise. Last month's release Good Bad Ugly, starring Ajith Kumar, and directed by Adhik Ravichandran, was just a cavalcade of scenes from Ajith's own filmography. It was termed a movie in service of his fans. Sounds fancy, but in reality it was just a pale pastiche of his previous works.

If borrowing from other's work is wrong (when overdone), deriving from your own material looks even more criminal. But when you make a habit of it, they actually praise you for creating a cinematic universe. Lokesh Kanagaraj, we are looking at you when we say this.

These new-fangled terms cannot couch the fact that originality is at an impossible premium in Tamil cinema now. Meta-narratives sound intellectual, but it is usually about the filmmaker’s fascination with cinema rather than about the characters or plot of his own cinema.

Veteran Gangai Amaran recently criticised the trend of using yesteryear songs in today's movies, and he said this is happening because the new compositions fail to resonate with audiences. It is true of the entire filmmaking process.

Not every film needs to break new ground. Some of the most successful films refine existing tropes rather than inventing entirely new ones. The key is how filmmakers borrow — whether they elevate the material or merely recycle it. Revisit the past, but don’t lose the present.