Culture

Question At Core Of Vivek Agnihotri’s ‘The Tashkent Files’-Do We Think We Deserve To Know The Truth About Lal Bahadur Shastri’s Death?

Shefali Vaidya

Apr 12, 2019, 08:32 PM | Updated 08:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Political thrillers are a genre rarely attempted by India filmmakers. Historically, Hindi films have largely stayed clear of tackling overtly political themes and even when films are made where the characters are based on real life politicians like Gulzar’s Aandhi, the reference is at best, oblique.

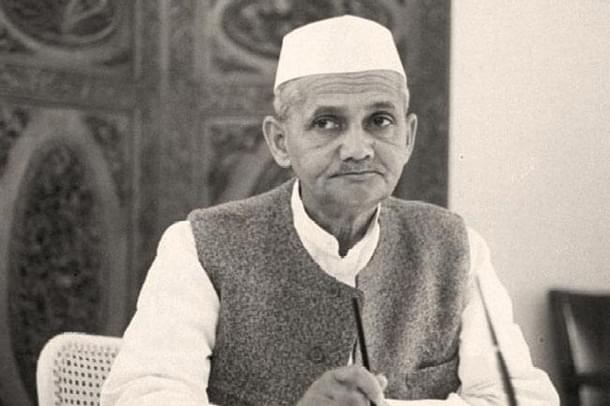

In The Tashkent Files, filmmaker and writer of the best-selling book, Urban Naxals , Vivek Agnihotri has made a daring attempt to tackle one of the greatest political mysteries of India, the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri, India’s second prime minister, who died in Tashkent in the erstwhile USSR, on January 11, 1966, the same night he signed an India-Pakistan peace accord with Ayub Khan after the 1965 war.

For years, there have been hushed whispers in the political corridors of Delhi that Shastri’s death was not caused because of a heart attack but by poisoning. Even Shastri’s wife, Lalita had expressed her suspicions regarding the same.

Yet, no filmmaker had shown the courage to tackle this story. In The Tashkent Files, Vivek Agnihotri takes a critical look at the mysteries surrounding Shastr’s sudden death.

The main character in the movie is a young, ambitious political journalist, Ragini Phule, who is hungry for a scoop. In the beginning, she is shown as journalist who doesn’t have too many scruples. She is tipped off by an anonymous caller who provides her with basic facts about the unanswered questions on Shastri’s death. Powered by this information, Ragini writes several articles questioning the official version regarding Shastri’s death.

Her articles force the government to form a committee headed by Opposition leader Shyam Sunder Tripathi, an ageing demagogue who is looking for a cause to revive his political career. As Ragini probes into the events leading to former prime minister’s death, she finds herself abandoning her cynicism to lose herself in the quest of truth.

The committee consists of members like well-heeled social worker Indira Joseph Roy, whose business is running NGOs, historian Aisha Ali Shah, who is meant to be a caricature of an ‘armchair historian’ and other characters like retired intelligence officers and judges. Most of the movie is based around the committee deliberations, in a format that reminds viewers of 12 Angry Men and Ek Ruka Hua Faisla.

It is clear from the screenplay that lots of painstaking research has gone into making this movie. The screenplay blends actual documentary footage and interviews with Shastri’s sons and journalists Kuldip Nayyar and Anuj Dhar deftly with the fictional narrative. Shot in grainy black and white, the heated debates and discussions in committee meetings make several sharp comments on contemporary politics as well.

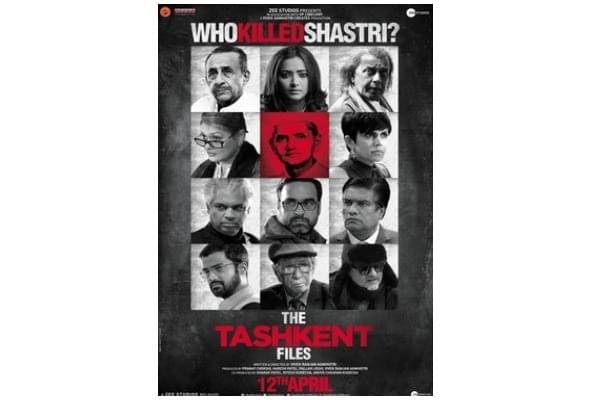

The film’s strength is its ensemble cast featuring several award winning actors like Mithun Chakraborty, Pallavi Joshi, Pankaj Tripathi, Mandira Bedi and Naseeruddin Shah. Mithun Chakraborty gives a bravura performance in a meaty role as Sham Sundar Tripathi, an ageing politician in search of a cause. Pankaj Tripathi and Pallavi Joshi are impactful in their respective roles, but Shweta Basu Prasad steals the show, particularly in the second half, with her believable angst.

However, the side track of her personal story of a failed marriage doesn't add much to the movie. The performances do become shrill at times, and the constant attempt to comment on contemporary politics does sound contrived at places.

The film asks several pertinent questions like why was no post-mortem ever conducted on Shastri’s body, even though his family asked for it? Why was Shastri served food on that fateful night not by his regular cook Ram Nath, but by Jan Mohammed, the cook of the then Indian consul? The movie also reveals to the viewers that the only two eye witnesses to Shastri’s death, his personal physician, Dr Chugh and his personal valet, Ram Nath, both died mysteriously in road accidents just before they were supposed to appear before an enquiry commission, and their deaths were not probed at all.

These are questions that have been raised in the past, but The Tashkent Files brings them into the mainstream. As the movie’s chief protagonists Ragini says, ‘it is not just about Shastriji, it is about the ordinary citizen’s right to truth’.

When the movie ends, the viewers are left with more than a hint at the truth, which might be unpalatable to several of today’s politicians.

Vivek Agnihotri is known to be a disruptive filmmaker who courts controversy. The Tashkent Files is no exception. It is a daring, disruptive film that deserved to be watched for the core question it asks, ‘do we, as a nation, deserve to know the truth?’

The writer is a freelance writer and newspaper columnist based in Pune.