Culture

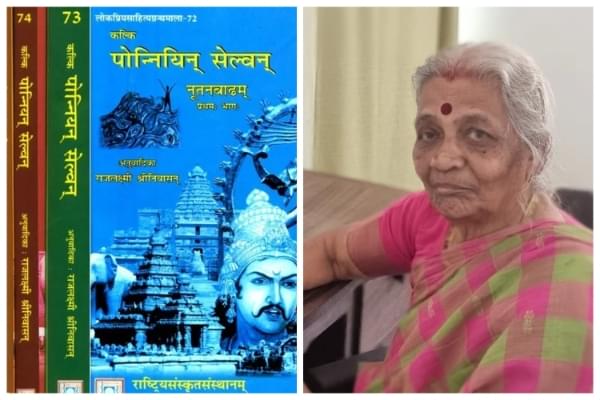

Tamil New Year Special: An Interview With Scholar Who Translated 'Ponniyin Selvan' Into Sanskrit

Aravindan Neelakandan

Apr 14, 2023, 02:57 AM | Updated 02:57 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Dr Rajalakshmi Srinivasan looks unassuming.

However, that unassuming personality hides her achievements which are worth quite a few life times.

She has been a lover of Indian languages all her life and she has channelled that love into translating literary works, ancient and modern, from various languages, chiefly into Sanskrit and Tamil.

She has translated Ramakirti Mahakavyam, the Thai version of the Ramayana into Tamil and was honoured for this feat by Her Highness the princess of Thailand.

She has translated the famous Sanskrit work Meghadootam into Tamil. She has translated the short stories of Bharati and another Tamil scholar Mu. Varadarasanar into Sanskrit.

She has translated the poems of Prime Minister Narendra Modi from Gujarati into both Tamil and Sanskrit for which he had tweeted his appreciation.

I congratulate Dr. Rajalakshmi Srinivasan for undertaking the effort of translating the poems into Sanskrit.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) November 20, 2016

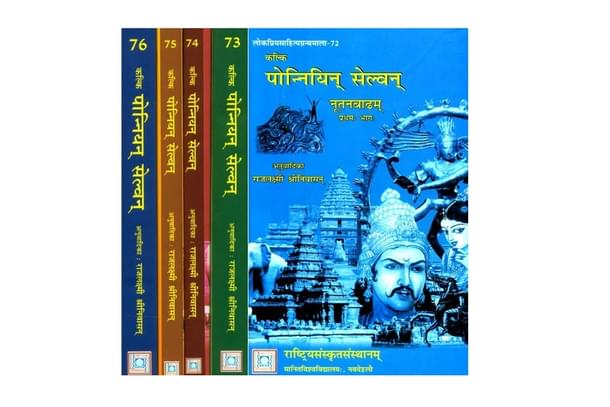

She has also translated the famous history fiction Ponniyin Selvan of Kalki Krishnamurti.

On the eve of Tamil New Year, Swarajya is honoured to publish this detailed interview of Dr Srinivasan.

You have translated quite a number of literary works into Sanskrit and vice versa. Can you give our readers a glimpse into your life and the inspirations that made you take up as life-mission such a noble and Bhagirathic endeavour?

Dr. RS: Since my childhood, I have had a deep interest and inclination towards Sanskrit. It is, I would say, my second mother tongue.

Whenever I come across an interesting story or information, I try to rewrite it in Sanskrit, and it gives me immense satisfaction and happiness. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that Sanskrit is considered a tough language, and when I used to recite or read it, listeners would appreciate it, which gave me a great boost, as though I possessed a special gem inside me.

As I progressed in life, I realised that my childhood passion for Sanskrit was not entirely untrue, and I continue to read writings in other languages as well.

This motivation continued as I grew up, and my parents, who were also into Sanskrit studies, taught me various slokas and literature.

My grandmother, who was a scholar of many languages, emphasized the importance of education, especially for girls, which was a great encouragement for me. After marriage, my husband has been very supportive of all my endeavors, which has made me feel very fortunate and lucky enough to continue pursuing my interests.

My father was the main anchor and inspiration, who gave me the gift of Sanskrit and our great heritage in so many small and big ways.

We lost our mother at a young age and it was our father who brought us up, also instilling values and fortifying us with Sanskrit slokas and works, right from a young age.

He also gave me an opportunity to render Ramayana Harikathas, which gave me exposure to different versions of Ramayana and other allied literatures such as those by Kamban, Tulasidas, and other Alwars Pasuram.

More pointedly, the purpose of the translation is to promote the cultural exchange and understanding between two distinct literary traditions.

Sanskrit and Tamil are both ancient and rich languages with long histories of literature and scholarship. By translating modern Tamil works into Sanskrit, I could help preserve and promote the works of contemporary writers in Tamil.

The general impression is that Sanskrit is a language meant for poetic expressions and scholarly works and spiritual treatises. How much flexibility you find In Sanskrit in translating a prose fiction?

Yes, it is true that Sanskrit is commonly associated with poetic expressions, scholarly works, and spiritual treatises. However, there is also a degree of flexibility in using Sanskrit to translate prose fiction.

Sanskrit is an ancient language that predates writing, and as such, poetic forms were crucial to preserving stories and information through oral tradition. This tradition carries over into Sanskrit literature, where poetic expression and storytelling are still prevalent.

Sanskrit spiritual treatises also contain various descriptions of human emotions and experiences, which lend themselves well to poetic expression.

That said, Sanskrit prose is unique in comparison to other languages. According to Sanskrit literary conventions, prose should be "ojas samasabhuyatvam etat gadyasya lakshanam (ओजस्समसभूयत्वमेतत् गद्यस्य लक्षणम् )", meaning it should be arresting and full of long compounds.

As a result, there were not many Sanskrit prose writers or prose works.

However, there are still examples of prose works with long compound words, such as the 19th-century biography of Shivaji, "Sivaraaja Vijayah," written by Ambika Datta Vyasa.

What prompted you to translate Ponniyin Selvan? Why not Sivakamiyin Sabadam (Vow of Sivakami) or Partipan kanavu (Dream of Partiban)?

Kalki was a prolific writer, having authored several long novels and short stories, which were published in the weekly magazine - Kalki.

While all his works are impressive, I chose to translate Ponniyin Selvan (PS) because it is a masterpiece that covers a wide range of subject matters.

It encompasses all emotions, rasas, and situations and features unique characters living in different situations with different feelings. The novel mainly revolves around the character of the Chola kings and the people who lived during that era.

While Sivakamiyin Sapatam is a beautifully written novel, it focuses primarily on Bharata Natyam dance, the life history of a great dancer, and her father, a sculptor. Partipan Kanavu, on the other hand, is a story that brings out the overwhelming feelings of a King who faces failure in his great ambitions.

PS, however, is a unique story that is difficult to abridge.

The novel revolves around the 18th day of the month Adi and ends almost on the Tiruvadirai day in the Margazhi month, covering only six months. Despite the limited time and space, the novel is vast, with umpteen actions, plots, and challenges.

The characters in PS follow dharma, satya, righteousness, and truth and are great warriors and disciplined people who were very happy during their ruling time.

This effective portrayal of such characters sparked my interest in translating this work into Sanskrit to make it available to Sanskrit language readers and showcase the beauty of this novel by Kalki.

Tell us the tough challenge that that you faced in translating Ponniyin Selvan

Translating a novel authored by great writers like Kalki is not a mere task, but a formidable one.

The very idea of it is daunting as it involves capturing a multitude of descriptions that are woven intricately into the narrative.

Finding suitable words to translate such beautiful descriptions is a time-consuming and challenging process. To achieve the desired result, I had to explore several sources in search of appropriate words that could convey the embedded feelings, thoughts, and humor accurately.

One exhilarating experience in translating Ponniyin Selvan?

It was the centenary year of Kalki Krishnamurthy, and I found myself engrossed in reading almost all of his novels and short stories. My particular interest was piqued by "Ponniyin Selvan."

I was captivated by Kalki's historical insights and his masterful way of weaving together various concepts and descriptions to delight connoisseurs of literature.

During this time, the Government of India selected me to receive a Senior Fellowship for translating "Ponniyin Selvan." This added to my already profound sense of ecstasy at fulfilling my long-cherished desire of translating this masterpiece of Kalki's into Sanskrit.

The propaganda is that Sanskrit is a dead language. Some scholars say that no new high quality original literatures like that of Kalidasa has appeared in Sanskrit in the last couple of centuries.

For example, every language has produced an original classic like Tolstoy's War and Peace. But Sanskrit has only scholars who study and master old classics and have not seen any outputs. Please give your response to this.

In my opinion, that criticism, not the dead language part, may be valid. Kalidasa was a gifted writer who was blessed by Mother Kali.

To comprehend Kalidasa's work is itself a blessing, as evidenced by the numerous commentaries in Sanskrit by both Indian and Western scholars.

It is impossible to create characters like Sakuntala and Dushyanta or write dramas like Kalidasa's. His writing style is straightforward, and he presents his ideas and noble thoughts in a lucid language that is known as "drakksha paka," or "eating grapes."

Unlike "kadali paka," where one peels the skin and eats bananas, or "narikela paka," where one goes to great lengths to enjoy the coconut pulp, Kalidasa's language is simple and accessible.

These poets lived with nature and had a deep understanding of human and supernatural elements, allowing their writing to flow naturally. Many poets were unconcerned with public opinion.

Even the author of the epic poem Kiratarjuniyam, which is titled "Bharave arthagauravam" or "Weight of Meaning," lived in extreme poverty but never approached the king. The writers were great, their thoughts were inexorable, and their language was refined and of the highest order, making them a rarity.

In Sakuntalam, King Dushyanta says, "Daratyagi bhavaamyoho parastri sparsa paamsulaH," which means that there were only two options in front of him: to accept or leave Sakuntala.

Leaving his own wife is a sin, and accepting another man's wife is also a sin. In this critical situation, he has to decide whether to accept Sakuntala, who is standing in front of him, or to leave her. He analyzes both situations calmly and selects the one that is the lesser of two evils. Such unique incidents are plenty in Sanskrit literature.

It is difficult to follow their writing or even to copy it. Under such circumstances, it may have been better not to create any new literary works that are not of that caliber but to preserve the old ones intact.

However, that does not mean that one should not create new literary works of their own. In this modern age, several writers have contributed to the literary wealth, including Abhiraja Rajendra Mishra, Hamsraj Agarwal, Shrutikanta Sharma, Radha Vallabh Tripathi, Ram Karan Sharma, and Reva Prasad Dvivedi, among many others.

As Ravindra Kumar Panda rightly says, "The twentieth century is an important period in the history of modern Sanskrit literature. Humanism is the form required for the country. It was the period when great minds were busy with innovative ideas for bringing out changes and innovations to establish humanism in a form required for the country."

My translation of Laghu kathaa Manjari, a collection of short stories in Sanskrit from the Purana period to the twentieth century, has been published by Sahitya Academy in both Tamil and the original Sanskrit.

It includes nearly sixty stories and addresses modern subjects such as dowry problems, widow problems, and various issues facing women. Satyavrat Shastri rightly remarks that "its subject matter, vocabulary, style, and technique make this literature modern."

Even with the same verbs and nominal suffixes, it has a different look, reflecting modern life, its struggles, thoughts, and ideas. Sanskrit literature of the modern age possesses new words in an old setting dished out in modern techniques.”

Till almost the 18th century, Sanskrit scholarship was part of being a Pandita, whether it is Sanskrit or Tamil. All great Tamil poets and Pandits have shown a great knowledge and admiration on Sanskrit. But the tradition seems to have stopped with Bharati. How does one revive it?

Many great Tamil poets and Pandits have shown a deep knowledge and admiration for Sanskrit. However, with the arrival of Mughals and more importantly the Britishers, our Indian languages and culture faced a precarious condition.

These rulers imposed their own language and culture in India and attempted to destroy our culture and institutions. Despite these difficulties and obstacles, Sanskrit has not lost its form, shape, or the richness of its tradition and high thoughts. It remains a language suitable for expressing all kinds of thoughts, moods, and situations.

Subramania Bharati, a great scholar of Sanskrit, composed three exquisite songs in Sanskrit. In order to revive the tradition of Sanskrit scholarship, we need to look back at our own history.

For instance, the manipravalam style was used to mix Sanskrit with the local vernacular languages of different regions. However, in the name of reviving and supporting regional languages, Sanskrit has lost some of its power and potential.

But Sanskrit has always nurtured a positive symbiotic relation with all regional languages in India – enriching them and getting enriched by them. Nurturing any regional language should also include nurturing Sanskrit traditions of that region as well.

We must practice our culture, way of life, and think positively in order to be a model for future generations.

It is said in the Gita, "uddhareta atmanaatmanam. na atmaanam avasaayayet (उद्धरेत आत्मानात्मानम्। न आत्मानम् अवसाययेत्)," which means that one should save oneself by oneself, and one should not lower oneself.

Sanskrit has not died, but it requires nurturing and attention. With time, it will automatically revive and come forth with extra vigour and strength. As nothing in the universe is stable, we need not worry about the fate of Sanskrit or any language or culture. Instead, we should focus on preserving our heritage and learning from it.

Who are your readers?

The question of whether a writer should write for their readers or for themselves is a common one.

While it is natural for writers to desire recognition and appreciation from their readers, it is important to consider the longevity of one's work.

As John Ruskin noted, many books are "books of the hour" and may not stand the test of time. In contrast, Sanskrit literature offers examples of works that were written primarily for the author's own satisfaction, yet continue to be appreciated by readers today.

The works of Kalidasa and Valmiki, for example, are still read and enjoyed in their original language. With this in mind, I personally do not write with a specific readership in mind or seek their validation. Instead, I write for my own satisfaction and to share my thoughts with those who appreciate Sanskrit literature.

While great authors often have a broad appeal, I believe that staying true to one's own interests and passions can lead to the most fulfilling and lasting works.

Late archaeologist Dr. Nagasami use to say ‘there is no Tamil culture but there is culture in Tamil’ which essentially means that Tamil has been great vehicle and contributer to what is today Indian culture of eternal dharma. Having done translation of modern literary impulses of Tamil into Sanskrit. What is your feeling? Please describe it for us.

I agree with Dr. Nagasami's statement that Tamil and Sanskrit are among the oldest languages of India. As someone who has studied and translated many ancient works in both languages, I see them as twin sisters.

Their origins, development, growth, and literature share many similarities, which suggest that both languages have evolved from the same cultural and linguistic roots.

Therefore, it is appropriate to consider Bharat as the mother of both languages.

Indian culture is deeply embedded in both Tamil and Sanskrit, and the two languages complement each other, building on the same ancient culture. By embracing both languages and their shared cultural heritage, India and Indians stand to benefit greatly.

What is your greatest strength in going strong for decades. Even now you are into some important translation works. Who is your greatest support in all these endeavours?

As I mentioned earlier, I am fortunate to have the unwavering support of my family, including my husband, children, and grandchildren, who have encouraged me in my literary and translation work. Their encouragement, along with the blessings of God, has helped me achieve so much in my life.

I am also grateful for the kind words and comments from my readers, which continue to inspire me. Currently, I am working on a translation of the ancient Tamil literature Manimekalai into Sanskrit, and I hope to complete this project to the satisfaction of both myself and my readers.

All of this, I believe, is by the grace of God. May God bless us all and may Bharat be a source of peace and happiness for the world.

What is your message to students of Tamil Nadu?

The student stage is a crucial period in one's life. What we learn during this time becomes deeply ingrained in our minds, and any missed opportunities due to false propaganda or peer pressure can result in a great loss and lifelong regret.

Learning any language during this stage can be beneficial, as it enables the preservation and appreciation of both old and new literature, providing insight into the thoughts of great men and Indian culture and heritage.

Those residing in Tamil Nadu are doubly blessed as both Tamil and Sanskrit are rich in cultural and spiritual significance. The easy-to-learn nature of Sanskrit makes it a valuable language to encourage for future generations.

Let us unite and fully savour the flavours of our literary heritage by embracing both languages and take pride in our Indian identity.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.