Culture

The Amritsar Model: Resurrecting A City’s Heritage For Its People

Ekta Chauhan

Feb 05, 2018, 07:43 PM | Updated 07:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The typical Indian approach to heritage management has mostly been limited to monuments, ignoring the areas and communities surrounding them.

Heritage sites are neglected and overcrowded, with inadequate basic services and infrastructure facilities such as water supply, sanitation, roads, etc. Basic amenities like toilets, signage and street lights seem to have disappeared. Moreover, there has been a clear lack of institutional capacity and planning to address these problems of historic areas.

This apathy towards India’s heritage was, however, broken by the National Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY), launched in 2014 by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. The stated aim of the scheme was to bring together urban planning, economic growth and heritage conservation in an inclusive manner for 12 selected cities.

As the scheme moves into its final leg, Swarajya decided to visit one of the HRIDAY cities, Amritsar, and assess what changes have been brought about to this holy city.

Amritsar centres around Shri Harmandir Sahib (popularly known as the Golden Temple). While it continues to be one of the most important religious and cultural centres for the Sikh community, its built heritage, traditional crafts and city design have been creaking under the weight of fast-paced urbanisation and investment-starved infrastructure and planning.

One could easily see a lack of open public spaces and a dwindling sense of community. The recommendations are, therefore, focussed on rebuilding the city’s glorious past and restoring its dignity across its heritage zones.

The Amritsar HRIDAY city plan, with an outlay of Rs 60 crore, identified five priority heritage zones, keeping in mind the layered history and monuments.

For all the five zones, access and improved mobility have been identified as a central theme and a large number of projects are dedicated to improving the outer and inner roads as well as walkability. While the work for most of the sites is still underway (until November 2018), one can see the impact of the scheme in several pockets of the city.

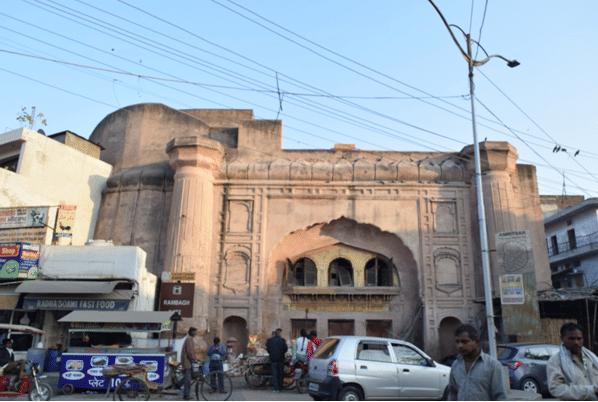

Rambagh Gate And Its Environs (Zone 4): It is the only surviving gate built by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Until a few years back, it was completely obscured and encroached upon and one could easily miss it while crossing the chowk in front of it. While the restoration and conservation of the gate and the rooms attached to it are an important part of the project, it goes beyond it to include adaptive reuse and regeneration of the precinct.

The insides of the Rambagh Gate houses a colonial era printing press, which is being restored. The terrace would house a restaurant and is being rebuilt. The work on a “people’s museum” is in its final stage, and would showcase the collective story of Amritsar and the community that lives around the gate.

As part of the landscaping of the roundabout in front of the gate, a table-top crossing has been built at the chowk to ease traffic movement and facilitate pedestrians. However, people in the area, when asked, said they were reluctant to use the new infrastructure as they are not accustomed to it. While some had misgivings about the “modern works”, others expressed hope, especially the shopkeepers, some of whom said the redevelopment of the area would bring in more tourists, and thus added revenue.

.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

Chalis Khoo And Pump House (Zone 5): During the British rule, Punjab had received mechanised systems of water sourcing. These canals and the pump house now form an important part of colonial industrial heritage and are key to understanding the evolution of the city and its irrigation system.

The site has 40 wells (khoo) and a large pump house that served as the water source to the city during that period. With time, however, the site lost its utility with its structures lying in a dilapidated state. The idea of restoration, especially at this site, aims at revitalising the structure and creating alternate spaces for recreation and public facilities.

Gol Bagh (Zone 3): This garden is one of the largest public spaces available in the city, but it was out of use due to lack of basic amenities. The area used to be covered with garbage and was being used as a dumping ground.

A boundary wall has been erected around the garden which has provided a sense of security to visitors, especially women. The muddy tracks are now covered with tiles and bricks. The provision of toilets, car parking spaces and lighting has further ensured that people can easily access and enjoy this space.

Roads Leading Up To Harmandir Sahib (Zone 1): This area has undergone a massive facelift in the past few years. One of the most ambitious and successful projects here has been storm water drain management. Until a few years ago, roads leading to the shrine would be regularly clogged with overflowing water from open drains, especially during the rainy season.

Most of the old city lanes had open drains, which were regularly clogged or encroached upon by the nearby shops. Under the scheme, 15 kilometres of underground drain pipes were cleaned, and new underground pipes were laid. As all the streets are very narrow, pipes were used to transport waste water outside of the city. As a result of this project, the streets are visibly clean and more pedestrian-friendly, especially for such an important shrine, which is visited by thousands of devotees every day.

One of the major achievements of the scheme has been a shift of focus away from just beautification to bring about people-centric heritage development, and create public spaces to improve the quality of life.

While the city may have made huge strides under the scheme, it still has a long way to go. The old city lanes continue to be occupied by some magnificent heritage buildings (old havelis and shops) albeit in dilapidated state.

Due to pressure of population, the lanes are further shrinking, old buildings being demolished to make way for new ones and residential areas are being used for commercial purposes. There is a dire need to improve and expand public spaces and amenities.

Without an integrated and long-term approach, Amritsar might become a victim of unplanned growth, and lose its architecture, tangible and intangible heritage resources, rich past and thus its very soul.

Ekta is a staff writer at Swarajya.