Culture

The Curious Case Of TN's Thalaivetti Muniyappan And Secular Discourse

Koenraad Elst

Aug 14, 2022, 10:31 PM | Updated 10:31 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

During the Ayodhya controversy, the ‘Eminent Historians’ and their supporters tried everything to counter the ever-mounting pile of evidence that there had been a Rama temple at the site where the Babri was built in the 16th century. One stratagem was to claim the site had been (apart from vacant land, a secular building, a Shiva temple or whatever) a Buddhist place of worship.

Actually, before the Islamic destruction, there had been quite a few Jaina and Buddhist places in Ayodhya, and they were well-known, but the contentious site was not among them.

Meanwhile, the archaeological excavations have confirmed that this was not a Buddhist site. But one failure is no reason for giving up. Indeed, now that the denial of Islamic temple destruction has lost all credibility, the attraction of turning Buddhism into a weapon for use in the secularist Jihad against Hinduism has only increased.

Out of the blue, a press report appeared about a temple controversy most of us had never heard about, in the far away Periyeri village in the district of Salem, Tamil Nadu.

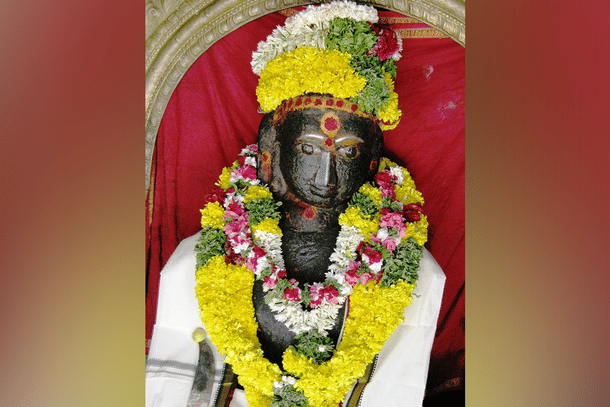

The Madras High Court has decreed that the worshippers of Thalaivetti Muniyappan are to be deprived of their temple because the central murti has been certified to have been a Buddha statue. So, we learn in “Idol in Salem temple is of the Buddha, not Hindu deity: Madras High Court”; then confirmed in “Madras HC directs restoring temple in Salem to its original Buddhist character – Has an important precedent just been set?” (Swarajyamag.com, 3 August 2022); and “Tamil Nadu's Thalaivetti Muniyappan Temple is Buddhist site, says Madras HC; halts further pooja” (Firstpost, 5 August 2022).

So, no puja for the deity will henceforth be allowed. On court order, the temple is secularised and entrusted to the Archaeological Survey of India, in expectation of a planned transfer to a local Buddhist society, presumably the Buddha Trust.

The verdict is the result of a case filed in 2011 by a local Buddhist, P Ranganathan, now deceased. The Court had the state’s Archaeological Department take a close look at the murti, and it found, after cleaning away the sandal paste and turmeric, that it had the so-called Mahālakṣaṇas, the marks distinguishing a Buddha from ordinary mortals, such as elongated earlobes. It was seated on a lotus in ardhapadmāsana (half lotus pose) with its hands in dhyana-mudrā (meditation hand-pose).

The High Court concluded that “the assumption of the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment (HR& CE) Department that it is a temple is no longer sustainable and the control must go into the hands of some other authority. (…) it will not be appropriate to permit the HR&CE Department to continue to treat this sculpture as Thalaivetti Muniappan. (…) treating the sculpture as that of Thalaivetti Muniappan would be against Buddhist doctrines.”

Now, what to make of this?

If you were to close a Shiva temple, you could cynically say to the deprived worshippers: “Go to another Shiva temple, there’s enough of them.” But Thalaivetti Muniyappan is a purely local deity. Closing his temple means depriving his worshippers of their focus of worship. Our knowledge of the law is a little vague, but is this even allowed to a court of law in a secular state?

No question-mark is needed when we look into this verdict in the light of the Places of Worship Act 1991, freezing the character of all places of worship as on 15 August 1947. The verdict flies in the face of this Act and is blatantly illegal. And it opens the door to similar shifts: all the mosques that proudly show off their history of temple destruction by containing a part of the temple in their architecture (such as the already contentious Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi) could readily be forced to re-become Hindu, overnight.

Back to this particular case. What exactly is the relationship between Thalaivetti Muniyappan and the Buddha? We find more details in a Buddhist article about recovered Buddha statues in South India: “Ancient Buddha Statues of Salem and Dharmapuri” by Yogi Prabodha Jñana and Yogini Abhaya Devi (21 October 2020, published on the wayofbodhi.org website). It explains:

“About a hundred years ago, someone found this broken Buddha statue with its body and head separated. The statue also had its nose broken. Someone affixed the head to the body but not in a proper way. The affixed figure looked odd, with its head slanting to the left. The nose that was added to the statue didn’t come out well. The outcome looked a little wrathful, unlike the usual Buddha statues. The eyes were also later painted in a wrathful way. So people consider it as some fierce local god and worship him that way with animal sacrifice. Thalaivetti means with a cut head.”

And Muniyappan is a Tamil way of saying: Muni Baba. This is not some mischievous Brahminical cover-up from Ambedkarite mythology, but a very open reference to a well-known Muni: Siddhartha Gautama, the Shakya-muni (“hermit of the Shakya nation”), after his Awakening also called the Buddha (“awakened one”).

So this deity is “the Muni with a cut head”. After his material recomposition, he looked wrathful, different from the standard Buddha, so he got a somewhat distinct persona. That’s how it goes in polytheist cultures, like that of these Tamil villagers.

This is something the secularists in the media, the courts and the Dravidianist parties won’t understand. Illiterate in religious matters, through their English-language textbooks they borrow some basic concepts from the Christian worldview. There, the word “religion” means a box-type division of the ideological landscape, excluding any other. Thus, when the Heathen Frankish king Clovis converted to Christianity in 496, his baptism father commanded him: “Now burn what you worshipped.” No compromise or half-way stance is possible, you have to burn all bridges with your former religion.

This view was unknown to, of all people, the Buddha, who recommended the continuation of the existing sacred sites, festivals and pilgrimages, and who integrated the Vedic gods and Rishis in his discourse. (The very first “conversion” to Buddhism, and where the converts were to “burn what they worshipped”, was by BR Ambedkar’s in 1956; though most of his followers continued to have a variety of Hindu gods on their house-altar.) But it was this view of religion that informed the unforgiving Christian and Muslim policy of iconoclasm: annihilate all reminders of Paganism.

Thus, the Islamic destruction of Buddhist monuments from Bamiyan to Nalanda originated in the conviction that the true religion could not tolerate any expression of a rival religion. That attitude, well-attested in Muslim history vis-à-vis Hinduism (including Buddhism), is then projected by the secularists onto Hinduism, or more precisely “Brahmanism”, vis-à-vis Buddhism. After all, “all religions are basically the same”, as even many unthinking Hindus will parrot after them.

Well, no, that breezy equation does not stand up to scrutiny. Thus, when the Muslim armies appeared in Nalanda Buddhist University, it was all over in no time; this, after 17 centuries when the Buddhist institutions had flourished unperturbed under Hindu rule. Is that no difference? Let’s listen to another passage in this Buddhist article:

“In the nearby town of Thiyaganur, the villagers worship a “majestic Buddha statue of 6ft height recovered from a field. We found it placed inside a beautiful meditation hall made by the collective effort of the villagers. A farmer donated the land, and the villagers pooled in money to build the meditation hall in 2013. They also constructed a lotus seat inside and installed the Buddha on that. Here, the Buddha is regarded according to his teachings and not as a God. This new home for the ancient statue exemplifies how to preserve ancient statues most beneficially.”

Look, that is how Hindus treat icons: they don’t break them, they worship them. They don’t even ask questions about its identity, and the difference between the formal name “Buddha” and the descriptive name “Thalaivetti Muniyappan” is inconsequential to them. It is nonetheless on this flimsy difference that the whole verdict depends.

It is now secularist discourse (and the Court verdict is entirely part of it) to claim that the Islamic treatment of other people’s gods merely follows an existing Hindu practice, equally intolerant. If so, then it shouldn’t be difficult to find numerous cases of Muslims installing statues of Shiva, Krishna or indeed the Buddha for worship. Any takers?

Koenraad Elst (°Leuven 1959) distinguished himself early on as eager to learn and to dissent. After a few hippie years he studied at the KU Leuven, obtaining MA degrees in Sinology, Indology and Philosophy. After a research stay at Benares Hindu University he did original fieldwork for a doctorate on Hindu nationalism, which he obtained magna cum laude in 1998. As an independent researcher he earned laurels and ostracism with his findings on hot items like Islam, multiculturalism and the secular state, the roots of Indo-European, the Ayodhya temple/mosque dispute and Mahatma Gandhi's legacy. He also published on the interface of religion and politics, correlative cosmologies, the dark side of Buddhism, the reinvention of Hinduism, technical points of Indian and Chinese philosophies, various language policy issues, Maoism, the renewed relevance of Confucius in conservatism, the increasing Asian stamp on integrating world civilization, direct democracy, the defence of threatened freedoms, and the Belgian question. Regarding religion, he combines human sympathy with substantive skepticism.