Culture

The Relevance of Rajaji: 42 Years Later

Seetha

Dec 25, 2014, 03:21 AM | Updated Feb 10, 2016, 05:45 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Modi was the only mainstream leader to pay respects on Twitter to Rajaji’s memory on his birth anniversary earlier this month. On Good Governance Day, which also happens to be Rajaji’s death anniversary, let’s hope he takes time to dip into Rajaji’s writings and pick up a few sensible tips on governance.

So, today is December 25.

For the followers of Jesus Christ, it is the day their Messiah was born. It is observed as Christmas.

For the Bharatiya Janata Party and its followers, it is the day on former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee was born. It is being observed as Good Governance Day.

Reza Aslan, author of the controversial book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, would probably think that there’s nothing out of place in observing Christmas Day as Good Governance Day. In his book, he argues that Jesus was, at the essence, a political person taking on the extortionist and hegemonic Roman state and the Jewish priesthood in cahoots with it—his was a movement for better governance, although he envisaged a kingdom ruled by God.

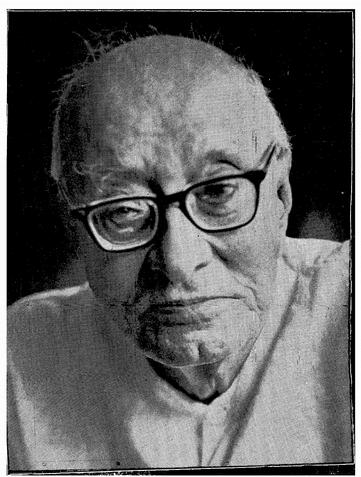

But today also marks another anniversary—the forty-second death anniversary of someone who had very firm ideas of governance and whose prescient words have largely been forgotten. C. Rajagopalachari or Rajaji was also a messiah—for individual and economic freedom in post-independence India. It was he who articulated a clear vision of good governance, one rooted in the role of the State, at a time when Vajpayee was perhaps still earning his political stripes. But it is not observed as any Day.

What does this government mean by good governance? We don’t have a clear idea apart from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s `minimum government, maximum governance’ slogan. But is it anything more than limiting the size of his cabinet (well, it was small before the cabinet expansion) and electronic delivery of services? And does a small-sized government necessarily ensure good governance?

Rajaji would have said no. Remember he was battling mis-governance by the Jawaharlal Nehru government, and cabinets in those days were small, not unwieldy as they became thirty years later. The term good governance did not find a place in the 21 Principles of the Swatantra Party, behind the formation of which he was the driving force, but what it set out was minimum government at its best.

For Rajaji and the Swatantra, an all-encompassing State was dangerous to individual freedom and to democracy. “The concentration of power in the State and its agencies is bound to kill the soul of the citizen and, with it, dry up his energy and the sources of true happiness,” he wrote in the Swarajya on 30 September 1961.

But this was not a state abdicating its responsibilities. The very first of the 21 Principles was a pledge to “social justice and equality of opportunity for all people without distinction of religion, caste, occupation or political affiliation”. The second principle spoke about “maximum freedom for the individual and minimum interference by the State consistent with the obligation to prevent and punish anti-social activities, to protect the weaker elements of society, and to create the conditions in which individual initiative will thrive and be fruitful.” The State, Rajaji said in an essay To Save Freedom in a monograph Why Swatantra, should not seek to replace the individual but help him achieve his goals.

With due respect to Vajpayee, he may have carried forward the process of economic reforms—even hastened its pace in some respects—but he did nothing really to expand individual freedom. Doing that would have had enormous beneficial consequences for governance. He should have read Rajaji who wrote: “When the State trespasses beyond what is legitimately within its province, it just hands over the management from those who are interested in frugal and efficient management to bureaucracy which is untrained and uninterested except in its own survival.”

The Modi government also does not seem to have internalised this wisdom.

Good governance, for Rajaji, would not have been compatible with encroachments into the private space through proposed laws against conversion (though, to be fair, it is the strident secularists who have created this situation) and the infamous Section 66 of the Information Technology Act (again, this is not something the Modi government is responsible for, but BJP supporters have not hesitated to use it) or needless interference in academics and educational institutions that goes beyond the much-needed reclaiming of the intellectual space from the left.

Good governance, in the Swatantra scheme of things, would not be compatible with wasteful subsidies which are cornered by the well-off and for the delivery of which there are more efficient alternatives. Equally incompatible would be a large public sector, something which Modi is keen to preserve. Rajaji conceded that there may be occasions when the government may have to set up an industry (remember this was in the 1950s and 1960s) but was firm that it should get out as soon as possible. “The business of government is government, not business,” the Swatantra Party firmly stated in its manifesto for the 1967 elections.

Vajpayee seemed to understand this and his government did privatise a few public sector undertakings. But on this, Modi has no qualms in following a Congress policy.

Modi was the only mainstream leader to pay respects on Twitter to Rajaji’s memory on his birth anniversary earlier this month. On Good Governance Day, let’s hope he takes time to dip into Rajaji’s writings and pick up a few sensible tips on governance.

Seetha is a senior journalist and author