Culture

Trading Traditions: A Journey To Assam's Jonbeel Mela, India’s Only Fair Where Barter Lives On

Nabaarun Barooah

Jan 20, 2025, 01:06 PM | Updated Jan 24, 2025, 06:37 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

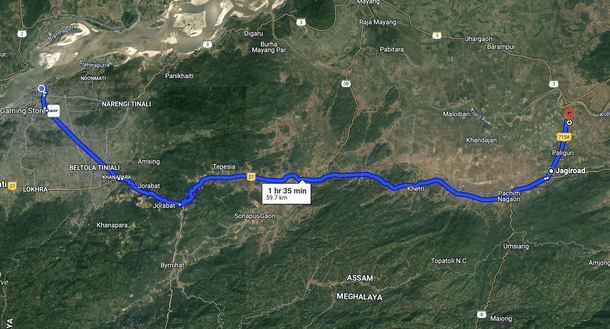

On the morning after Magh Bihu, I left Guwahati around 8:30 am, with the city still waking up to the first light of day. The cool winter air nipped at my face as I set out for the eastern part of Assam, heading toward the legendary Jonbeel Mela. It was a quiet, tranquil morning; the roads were relatively free of traffic, and the landscape unfolded in serene shades of green and brown. The morning mist clung to the hills, softening the edges of the towering trees and villages that dotted the path.

As I travelled out of Guwahati, the bustling city gave way to rural Assam. To one side, the rolling hills of Meghalaya stretched out, while on the other, vast rice paddies extended to the horizon. Occasionally, small tea gardens hugged the hillsides, and herds of cows grazed lazily by the roadside. The hum of rural life — villagers gathering firewood and the chatter of people heading to the fair — added a distinct rhythm to the journey.

The further we drove, the more the energy of the surrounding landscape seemed to seep into me. By the time we crossed Jagiroad, I could feel the buzz of excitement building in the air. Near the mela (fair) grounds, the area was already teeming with activity — cars, motorbikes, and rickshaws ferried visitors, traders, and locals to the fair. Despite the presence of modern vehicles, the atmosphere felt distinctly timeless, as if I had stepped into a different era.

A Glimpse Into Tradition

By 9:45 am, we arrived at the mela site — less than two hours after leaving Guwahati. As I stepped out of the vehicle, I was immediately struck by the stark contrast between the modern bustle I had just left behind and the centuries-old tradition that awaited me here.

The scene before me was a vibrant blend of colors and sounds. Traditional bamboo stalls were being assembled under the shade of large, sprawling trees. The air buzzed with activity — the rhythmic sounds of hammers on wood, the clatter of metal, and the joyous laughter of people reconnecting with old friends.

As I walked further into the fairground, I saw families — some from the nearby hills, others from distant corners of Assam and Meghalaya — arriving with bundles of produce, baskets of fish, and stacks of handwoven textiles. The sight was captivating: the vivid hues of handwoven clothing, the lush green of freshly harvested vegetables, and the earthy tones of handmade pottery combined to create an atmosphere both lively and steeped in tradition.

The Jonbeel Mela, celebrated for over 500 years, holds a special place in the hearts of the tribes in Assam and Meghalaya. It was first organised by the Tiwa King, Gobha Raja, as a means to foster peace and harmony among tribes — primarily the Tiwas and Karbis of Assam, and the Khasis and Jaintias of Meghalaya.

The fair’s original purpose was not just to exchange goods but to bring people together, fostering dialogue about politics and establishing cooperation among tribes that had once been at odds. In fact, even today, the nominal Gobha Raja and his courtiers attend the fair in their traditional royal attire, playing the symbolic role of "collecting taxes," a practice that honours the historical connection between leadership and community welfare.

I quickly learned that the mela had yet to reach its full swing, however, there was already a palpable energy in the air, especially as the first wave of exchanges began. The stage was being set for what promised to be an extraordinary exchange.

A Sacred Beginning

The Agni Puja, a traditional fire ritual that marks the beginning of the mela, was already underway by the time I arrived. A group of priests, adorned in simple yet ceremonial attire, stood gathered around the sacred fire. Smoke spiralled upward, mingling with the crisp winter air, while rhythmic drumbeats echoed faintly in the distance.

The flame symbolised purification and a profound connection to the earth, ancestors, and divine forces watching over the land. Carefully tended by the priests, the fire held sacred significance. Nearby, the Gobha Raja and his subjects offered prayers to Agni, the fire god, seeking blessings for the prosperity of the fair and the well-being of the community.

With the puja concluded, attention shifted to the next tradition of the mela: community fishing in Jonbeel Lake, aptly named "Moon Wetland." As I approached, the lake presented a mesmerizing sight. Crescent-shaped and nestled in a lush valley, it lay tranquil, bordered by tall reeds and vibrant greenery. The still waters shimmered, disturbed only by the ripples of nets cast by men, women, and children working together.

There was an unspoken harmony in their movements — a fluidity that spoke of shared purpose and deep-rooted tradition. The dark, reflective waters seemed to carry the weight of their collective effort.

I observed fishermen and women from various communities wading into the shallow waters, casting their large nets and other traditional fishing tools into the lake and pulling them in with a mix of concentration and camaraderie. It was a rare moment of collective labor, unmarked by competition or haste, where everyone seemed focused on the common goal: filling their baskets with enough fish to ensure their families’ sustenance for the months to come.

This ritual was about much more than just food — it was about community. People of all ages participated, from young children watching in awe to elderly women offering guidance to the younger fishermen. The barter of fish and other goods would come later; for now, the collective labor carried a significance beyond any transaction. It was as if the lake itself was a symbol of abundance that belonged to everyone, and the work of bringing its bounty to shore was an offering of respect.

The Barter System

Once the fishing concluded, the atmosphere shifted, and the Jonbeel Mela came alive in full swing. The lakeside stalls buzzed with activity, offering a dazzling array of goods: fresh vegetables, live animals, handwoven garments, bamboo crafts, pottery, and fragrant spices. The energy in the air felt almost timeless as if stepping back into an ancient tradition.

At the heart of Jonbeel Mela lies the barter system, the primary mode of exchange long before currency took over. Historically, this fair served as a gathering point for tribes to exchange goods such as cooked food, home-grown vegetables, animals, handloom products, and crafts.

The hill tribes from Meghalaya bring their forest products, herbs, wild berries, and spices, trading them for the items abundant in the plains, like rice, vegetables and fish. This exchange system ensured that people shared their surplus and obtained what they needed, fostering an atmosphere of mutual respect, fairness, and community. Importantly, the absence of money meant that the value of an item was not defined by its monetary worth but by the needs and relationships of the people involved.

What struck me most was the fluidity of the exchanges. There was no money involved; instead, people from different tribes offered what they had in abundance and took what they needed. A Khasi woman, for instance, traded jars of her famous fermented bamboo shoot chutney for some fish. A Tiwa farmer exchanged ginger, garlic and bhüt jolokia (ghost chilly) for a couple of brooms. It was an economic system based on mutual need, trust and a long-standing sense of community.

In a world where commercial trade and modern financial systems dominate, the barter system at Jonbeel Mela is a rare and significant practice. It endures because it reflects core tribal values: cooperation, equality, and respect for nature and tradition. While modern influences have crept in, and many traders now use digital payment methods like UPI, the fair continues to stand as a living tradition, sustaining not just economic life but also the cultural fabric that has bound these tribes together for centuries.

There was no rush, no pressure — just an innate understanding that these exchanges went beyond material gain. They reflected the deep-rooted ties that bound these different tribes together. Far from being an outdated relic, the barter system was a bridge connecting the past and present, anchoring the community in its shared heritage.

I wandered from stall to stall, soaking in the sense of connection. I witnessed the importance of the mela in sustaining the community’s way of life. It wasn’t merely a fair; it was a cultural festival that symbolised the tribe’s collective survival and resilience in a rapidly changing world.

The Spirit Of Jonbeel

By the time I left Jonbeel Mela, the sun had already begun its descent. The fair was still in full swing, but I had to start my journey back to Guwahati. As I retraced my steps, I reflected on the day’s experiences — the simplicity of the rituals, the profound sense of community, and the timelessness of the barter system. The journey back felt differen — more grounded, more aware of the delicate balance between tradition and modernity.

The road was quiet as I passed through the same rolling hills and villages, with the evening light casting long shadows across the landscape. The sights and sounds of Jonbeel Mela — the laughter, the chatter, and the vibrant energy of the barter — remained vivid in my mind. It wasn’t just a fair; it was a reminder that, even in a world dominated by digital transactions and global markets, there are still places where tradition holds firm, and the value of human connection outweighs all else.

That evening, as I returned home, I left Jonbeel behind but carried its spirit with me — an enduring experience of an ancient tradition, alive and thriving in the heart of Assam.

Nabaarun Barooah is an author and commentator.