Culture

Two Temples Near Kanchi In Ruins Despite Owning Hundreds Of Acres, Even As Tenants Flourish

MR Subramani

Nov 17, 2018, 12:14 PM | Updated 12:14 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On 16 January 2014, a giant wheel at Queensland Amusement Park in suburban Chennai malfunctioned, leaving 18 persons injured. The father of one of the injured persons filed a complaint with the Nazarathpet police station, under whose limits the amusement park falls. The police station issued a community service register. After that, not much was heard of the case, nor did the media follow up.

A year later, a school boy was drowned in the pool of the amusement park. In this incident, the authorities of the school, who took the boy on an excursion, were blamed. It’s unclear if any case was registered against the amusement park.

In both incidents, one aspect was never questioned – how can the amusement park function when it was asked to vacate the lands it was operating on by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR&CE) Department?

The amusement park owner had taken the land on which the park operated to carry out agricultural activities. Selvaraj, the owner of Queensland, had taken the lands on lease from Kasi Viswanathar (Shiva) Temple and Sri Venugopala Swamy (Vishnu) Temple at Pappanchatram near Poonamallee in Kanchipuram district for farming activities in 1991.

Admitting a petition filed by the temple administration, a local court ruled in 2008 that the lessee had violated the lease agreement by indulging in commercial activities. An appeal against the order was dismissed by the court in 2013.

St John’s International Residential School is a kilometre away from Queensland. In the suit in which the amusement park was restrained from carrying out commercial activities, the school authorities were a party and were directed similarly. The problem with the amusement park and the school, which are prospering, is that lands for both were taken on lease for farming in 1991 – when Sriperumbudur was a far cry from being the “Detroit of Asia” that it is today.

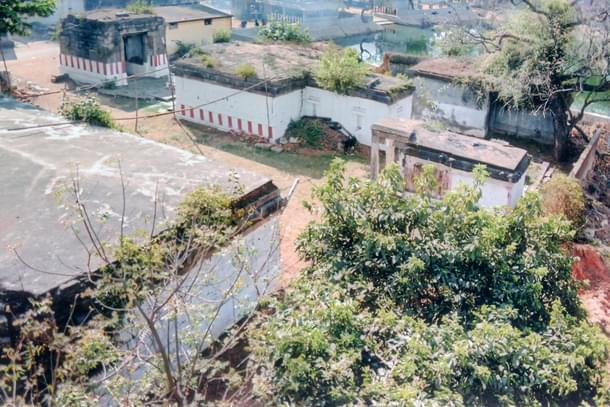

Just off the Bengaluru-Chennai National Highway between Poonamallee and Kanchipuram is Pappanchatram, where Kasi Viswanathar and Sri Venugopala Swamy Temples present a pathetic sight. Both temples are in one complex that doesn’t even have a compound wall. Cattle – cows, calves, and goats – enter the temple freely, and the locals even use the complex to keep their cattle on a leash.

The temple is in a shambles with structures disintegrating. It would be hard to believe that the temple owns 177.7 acres, including the land on which the Queensland Amusement Park and St John’s International Residential School are operating.

Doraiswamy Gurukkal, who has been the priest for the Kasi Viswanathar Temple since 1974, says the temple had two halls (mandapams) for marriages and events. Both have been damaged, and today, there are no signs of them being the big halls that they were at one time.

“Sri Chandrasekhara Saraswathi Swamigal of Kanchi Kamakoti Mutt used to stay in the mandap at least 15 days in a year. I have seen him come here in the 1980s. He would take a bath in the temple tank early in the morning and then conduct poojas and daily rituals,” reminisces Gurukkal, even as he shoos away a goat trying to enter the Shiva temple.

The origin of the temple dates back to the 1800s when a zamindar (landowner) called Venkaiah travelled to Varanasi to find a solution to his personal problems. There, he came across a priest who gave him a Shivalinga the size of a football. The priest asked Venkaiah to build a temple for the Shivalinga at a place where he finds the land gold in colour.

On his way back, Venkaiah found that at Pappanchatram the land was gold in colour. He proceeded to buy some 1,750 acres there. He then built the Shiva temple there along with one for Vishnu. In addition to the temple, a quarters was constructed for temple priests to live, while the two big halls also came up.

Before breathing his last, Venkaiah, in his will, wrote in all the lands of two villages – Irunkottai is the other – he owned for the temple so that poojas could be conducted without any hurdle, and the premises could be maintained properly, says S Kanniappan, an elder in Pappanchatram who now heads a devotee sabha (assembly) to retrieve the temple to its old glory.

Kanniappan and Gurukkal say there are three inscriptions in the temple that vouch for the donation of the lands to both temples. “Things turned bad for the temples when the Madras Estates (Abolition and Conversion into Ryotwari) Act, 1948 – popularly known as the Ryotwari Act – was implemented. The surveyor who came to see these lands wrote all these as orphaned, thus making it lose many acres,” says Kaniappan.

“The irony is that of the 1,500 acres he bought, Venkaiah donated nearly 1,000 acres for the lake that is now Sembarambakkam Lake. The rest were the ones donated to these temples, but even that they are unable to take advantage of,” says Gurukkal.

Two things happened when most of the temple lands were taken away in 1951 after the Ryotwari Act was implemented. “One, some of the temple officials were smart and dedicated and got the lands on which the temples existed registered in the deities’ name. Second, the temple management moved the Assistant Settlement Officer, Tirupattur, in 1956 to retrieve the lost lands, but the petition was dismissed,” says Gurukkal.

A move by the Dasaprakash Group to buy 10 acres of land in the village in 1983 proved to be a blessing in disguise. The group wanted to buy the lands behind the 10 acres it had bought near the St John’s International Residential School. It said it would pay the HR&CE Department and take the land on lease.

The temple management opposed this move and filed a petition in the Madras High Court. In 1993, the High Court ruled that the lands belonged to the temple and struck down the Dasaprakash Group deal. An appeal by the group was dismissed by the Supreme Court. “After that, the Dasaprakash Group sold off the land and left the place,” says Kanniappan.

“Some people now enjoy the temple land in the village. But they can only enjoy as long as they are alive,” says Gurukkal, adding that the problem for the temples is that the HR&CE Department is yet to give the management the registration document for these lands.

“We have been time and again reminding the HR&CE Department. We have pointed to the Queensland and St John’s School case. But no government official is willing to act or do the needful to vacate them. They (the amusement park and the school) are thriving, but look at the temples,” rues Kanniappan.

“The Queensland Amusement Park and St John’s School paid the lease rental the first year to avoid paying taxes. After that, they haven’t paid a single paisa as rent to the temple,” regrets Gurukkal.

“It is almost a month since we offered cooked rice to the deity,” regrets Rajagopal, priest of Sri Venugopala Swamy Temple. A kitchen or madapalli is under construction for the purpose. “We have been seeking donations to construct the madapalli, but they have not been forthcoming,” says Kanniappan.

The problem, according to Gurukkal, is that the villagers don’t want the temple to be restored to its former glory. “They fear that they will all be asked to vacate the temple lands if it is restored. So, they have all tightened their purse strings,” he says.

“It is not that people don’t come to the temple or celebrate festivals in the premises. Pradosham (the day that comes two days ahead of the full moon and new moon) and Vilakku (lamp) pooja sees many devotees turning up,” says Kanniappan, adding that despite all this the temple continues to suffer.

Asked about the income of the temples, Doraiswamy Gurukkal twirls his wrist and palm to say nothing. “That’s why efforts are being made to retrieve the 177.7 acres and ensure the temples will have a decent income for poojas and maintenance,” he says.

Gurukkal himself draws a meagre salary of Rs 300 per month from the HR&CE Department. “I get my salary on an annual basis, and there are five years of arrears,” he claims, adding that he complements his income by being an astrologer when he is not at the temple.

Rajagopal, on the other hand, is lucky, as he is paid Rs 6,000 a month as salary by the devotee sabha. He even gets Rs 1,000 as allowance to travel 30 km one way every day from his home at Thiruvallur to the Sri Venugopala Swamy Temple.

Lack of proper maintenance is telling on the temple. The walls of the temple are giving way, and plants are growing on the walls. The temples also lack proper lighting, and the inside of both temples are dark with poor lighting.

“The temple has an odd luck. People keep fighting over trivial issues for any temple event. But when the day of the event comes, the most bitter opponent would be the first to attend, and all rivalries are buried. We hope this will happen with the restoration of the temples and their lands,” says Gurukkal, hoping the lands on which the Queensland Amusement Park and St John’s International Residential School exist will be restored.

This article is part of the Swarajya heritage programme. If you liked this article and would like us to do more of the kind, consider being a sponsor – you can contribute as little as Rs 2,999. Read more here.