Culture

Why Shiva As Tripurantaka Must Act On ‘Old Establishment’ Demons This Karthik Purnima

Aravindan Neelakandan

Nov 12, 2019, 04:07 PM | Updated 04:06 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

While for us Tamils, the Karthika Pournami (Purnima) is yet to come, for other parts of India it is today. The puranic and historic significance of the day is worth dwelling upon.

Here, let us take Tripurantaka — Shiva as the destroyer of Tripura.

Today is the day when Shiva destroyed the asuras of Tripura – the three moving fortress cities made of iron, silver and gold. The three asuras who possessed them were Tarakaksha, Vidyunmali and Kamalaksha.

The puranic tradition has it that these three asuras were the sons of Tarakasura, who fought with the aid of Krauncha Giri – a mountain that could create delusions in the minds of the spiritual warriors. Ultimately, Murugan, son of Shiva, destroyed the Krauncha mountain with his vel or spear of divine wisdom, and slayed Tarakasura.

The three sons of Tarakasura performed harsh penances to please Shiva who granted them the boon of three invincible cities, the Tripura. Of course, the only way they could be destroyed was when they got aligned in the same line which would never happen except for a brief moment that occurs very rarely – when the Pushya Nakshatra arises in conjunction with full moon.

When the moment of that rare event nears, the only one who could shoot such an arrow that would destroy all the three metallic cities had to be found, which naturally was Shiva himself.

So, all the forces of goodness get into action. The Earth became his chariot, vedas became the wheels of the chariot, and Brahma the charioteer. His bow was the cosmic axis and mount, the Meru and the bowstring was the cosmic serpent. The arrow was Agni himself. And then, he shot the arrow.

Or did he?

In South India, there are other interesting dimensions to this purana. The devas forgot to invoke Ganesha when they made this cosmic chariot for Shiva. The result was disastrous. When Shiva got into the chariot, the axle broke. Then the deity of auspicious beginnings, Ganesha, was propitiated, and the chariot was repaired.

As the moment drew close, pride started to slowly creep into the mind of devas. They thought that this extraordinary feat that Shiva was going to perform would not be possible without them.

Shiva, the omniscient one, realised this. He simply smiled (or laughed) and lo! He needed no arrow or bow, chariot or charioteer. Simply the sparks from that laughter burnt the Tripura.

Thus Shiva becomes Tripurantaka – a form that will soon become endearing to his devotees all over India — especially in South India.

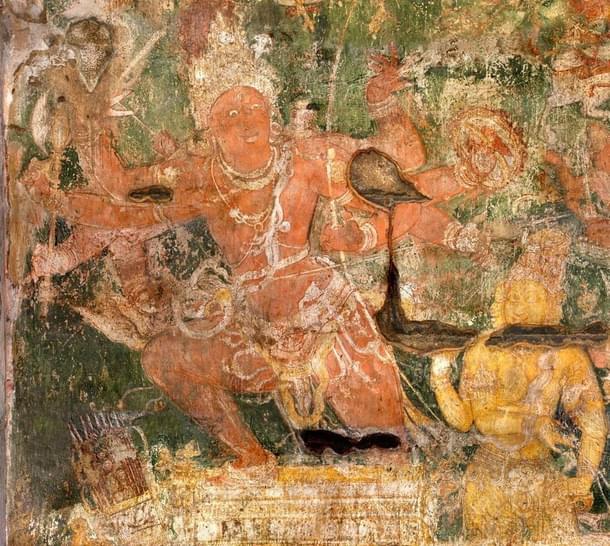

Raja Raja Chola, in his great Brahadeeswara Temple in Thanjavur, had immortalised this fiery laughter of Shiva as Tripurantaka. It is one of the most astounding works in the history of paintings. As usual, our historians of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) vintage try to belittle it as much as possible, and try to explain this as representation of royal power rather than genuine spirituality.

Historian Upinder Singh while discussing "religious and political symbolism in Thanjavur temple", initially presents the highly Hinduphobic JNU historian Dr R Champakalakshmi’s reductionist ‘monodimensional’ view of Tripurantaka:

R Champakalakshmi points out that the prominence of the Tripurantaka form of Shiva in the Tanjavur temple has to be understood as a part of the temple’s larger iconographic programme. Since the temple was symbol of Rajaraja’s power, the Tripurantaka form must have had a special significance as well. Its association with the theme of victory over evil demons may have had a special appeal for a king who projected himself as a great conqueror.

The view of Dr Champakalakshmi is derived essentially from three biases: Marxist bias that religion serves only as a tool for power; then the JNU-induced aversion towards anything Hindu, which is reflected in many of her interviews or her Hinduphobic nature, and third the colonial Indological view that cannot see Hindu iconography as having no value other than political.

The last category can be seen in a paper by German Indologist Gerd Mevissen, who identifies two forms in “early stone sculptures of Tripurantaka in South India”.

The upper Dravidadesa tradition ... emphasizes the aggressive aspect of this murti; these images, shown in a fierceful fighting attitude, refer mainly to military campaigns and reflect the claim of paramount overlordship. The Lower Dravidadesa tradition, on the other hand seems to emphasize the protective aspect by depicting the god placidly smiling with his bow unstrung and placed towards his side, thus rather reflecting a prevalent military threat than an actual campaign against an enemy. All this indicates that the Tripurantaka form of Shiva was understood and intentionally used as a political murti.Gerd J R Mevissen, ‘Early Stone Sculptures of Trtpurantaka in South India’ in “Studies on Art Archeology and Indology: Papers presented in memory of Dr Haribishnu Sarkar” Vol I (Ed Arundhati Banerji), 2006, P 135

Note that this German Indologist seems to be totally ignorant of the purana tradition of Shiva destroying Tripura with the smile. So in both the depictions, Shiva is actually portrayed in the art of destruction. Yet from his ignorance of tradition, the Indologist not only builds an entire train of explanations, and concludes quite confidently that “the Tripurantaka form of Shiva was understood and intentionally used as a political murti”.

This fallacy comes from the deep colonial conviction that the murtis of Hindu tradition cannot have been sculpted with their own inherent value but being ‘false gods’ only served political ends. One does not have to be a believing Christian or even an explicit Hindu hater to internalise this view. Indology and colonial-Marxist historiography mostly impart this frame for understanding Hindu culture and divine icons.

Fortunately, Dr Upinder Singh does not stop with this belittling interpretation.

"But there are other angles as well,” she points out. She goes into a detailed scholarly study of Tripurantaka. She highlights various aspects of several devas coming together for this mission, as noted above. But she leaves out the destruction with laughter in order to also destroy the egos of the devas. But for a historian coming from Delhi establishment the detailed study that she had carried out is refreshingly better than her predecessors like Romila Thapar, who used only Hinduphobic approach peppered with Marxism. Dr Singh elaborates:

After destruction of the three cities, Shiva took on two of them as His doorkeepers and the third as His drummer. Like many other Puranic stories there is a sub-text which in this case emphasizes, the subordination of other gods to Shiva. The Tripurantaka form of Shiva may therefore have tied in well with Rajaraja’s attempt to raise the Shaiva cult to a position of pre-eminence in his kingdom. We can also note a mural in the south wall of chamber 5 which seems to represent Rajaraja Chola himself as a prime devotee of Siva as Dakshinamurti, a form in which god preaches the highest knowledge to various sages.‘A History of Ancient and Early Medieval’, P 560

While the observation of Dr Upinder Singh is definitely a better one than that of Dr Champakalakshmi, there are still crucial elements that a student of Hindu religious culture, iconography and statecraft should know.

Tamil Shaivite mystic and writer Tirumular is usually placed by historians in the period between the sixth and eighth centuries CE. His work Thirumanthiram, a text that does samanvaya of various spiritual streams then extant, Saivaite, Shakthic, Yogic, Tantric etc, provides a yogic-psychological interpretation of Tripurantaka, which now forms one of the eight great valorous deeds of Shiva.

Sings Tirumula:

Our Lord primordial

One who has waters decorating

His reddened matted hairlocks,

He did burn to ashes Tripura,

so say the fools.

The Tripura are the three inner impurities.

It is this He burns

Who can really realise His deed?

(Thirumurai 10: Thirumanthiram Tantra-II 2:5)

Here, the three inner impurities are egotism, karmic bonds and the illusion of naive reality or maya. Of these, ego being born along with the corporeal body is considered as the last and toughest impurity to remove.

Then what does the depiction of Shiva as the laughing Tripurantaka signify? It signifies not only the destruction of the three impurities but also the destruction of ego or sense of self-pride in those who considered themselves the instruments or the army of Shiva.

Now, let us go back to Raja Raja Chola. Given the fact that he considered himself Shivapadasekara or the one who holds the feet of Shiva in his head, he identified himself more with the devotees or at best the assistants of Shiva than with the lord himself.

And Tripurantaka, which he chose to depict in the painting in the grandest temple he built, showed Shiva mounted on the grandest cosmic chariot. He chose not to use the chariot because he sensed the ego developing among those who built the chariot.

In other words, the painting and the depiction of Tripurantaka by Chola emperor Raja Raja was more a reminder that the ruler made to himself that he should be humble before Shiva rather than identify himself with Shiva as a ruler.

If in the yogic psychology the Tripura represents the three inner impurities, then perhaps, the Marxist, colonial and Hinduphobic approaches to our history represent the Tripura of old establishment historiography.

Let us hope this Karthik Purnima, celebrated in many parts of India, the smile of Shiva acts upon this Tripura as well.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.