Culture

Wrestling To Survive: The Vanishing ‘Garadi Manes’ of Royal Mysuru

Harsha Bhat

Oct 11, 2018, 02:00 PM | Updated 02:00 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

‘Wrestling is to Mysore what Football is to Brazil’, and other such claims describing the wrestling history of Mysore (now Mysuru) urged me to see for myself what this ‘wrestling hub of yore’ now looked like. Having heard that vajramushti kalaga or the armed fistfight that ends with a drop of blood, heralds the Dasara celebrations at the Mysore Palace, I visited Mysuru last week as the city was getting decked up for the annual carnival.

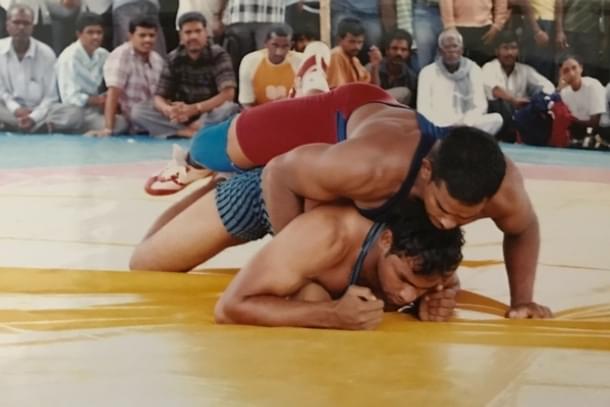

The scent of petrichor, thanks to the unexpected showers, added to the festive feel as much as the sights of the sidewalks that were being painted and lights hung all over the city. But two days of touring the city and encountering various even facets of the world of kushti (wrestling) left me stirred. In a few days, wrestlers from across the country would descend on this city of palaces to literally fight it out for the Dasara Wrestling Championship titles.

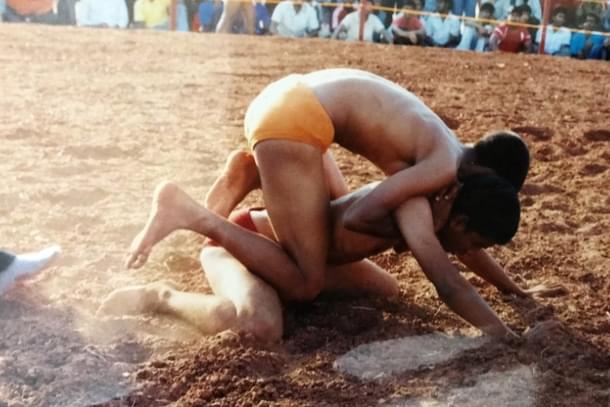

But the wrestlers I looked forward to meet were those that were groomed in the traditional Indic way, in garadis (house of wrestlers), with the komana or the loin cloth tied tight and mud rubbed on their bodies.

I stood at the crossroads. On one end was the palace shimmering under the setting sun, and to the right, and in stark contrast, was the garadi mane that I had walked out of with a heavy heart.

Earlier that evening, I was all geared to meet the pehelwans (wrestlers) and watch them prepare for the traditional wrestling competition or the naada kusti (local wrestling) at the Dussera Kusti Competition which kicks off today (10 October). I waited at the Gandhi Square in Mysuru to be led by a pehelwan into a bylane, a kachcha road made worse by the midday showers. I had to cross a stinky public toilet to find the entrance of a traditional structure, its whitewashed limestone walls lined with the good old mud red patterns. I followed the pehelwan, who showed me the marble board above announcing, once proudly and now meekly, its name, and then ducked his head to enter a space, which for over 150 years now had muscled up hundreds of wrestlers.

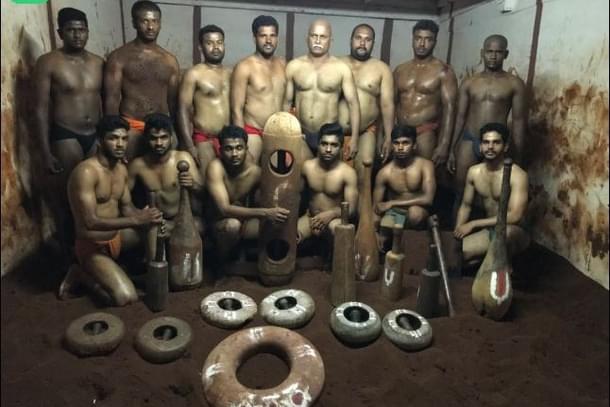

As I entered and took off my footwear, young pehelwan Jeevan instructed me to wash my hands and feet as he did the same before entering the room. One of the key garadis of Mysuru, the Pakeer Ahmed Sahebara Garadi is one of the two important schools of wrestling to which many other wrestling houses owe their allegiance.

This is one of the few that stood the test of time.

Once, the city was a hub for wrestling. There were over 150 garadi manes and almost every house had a wrestler. Wrestlers from other parts of the country feared a bout with a wrestler from Mysuru. Such was the training, such were the wrestlers, say senior wrestlers at the garadi. “But those are all tales of a bygone era,” muse some of the veterans.

“From manegondu pehelwan (one pehelwan per house) it has come to oorigobba pehelwan (a wrestler per village). From 150 the number of garadis has come down to around 50. And the ones that exist also have shrunk in size and are hardly being able to accommodate all the wrestlers. Yet, the talent hasn't diminished,”says veteran wrestler Ganesh Shetty. He blesses the young wrestlers, who touch his feet and take his blessings before they begin their workout for the evening.

Professor K R Rangaiah, working president of the Karnataka Wrestling Association is angry at the plight of the wrestlers today and wishes the nada kusti wrestlers who train in garadis move to point wrestling. Prof Rangaiah has to his credit the title of being the city’s only wrestler who also pursued education and got himself a job as a professor in a college. “Nada kusti alone will get them nothing, as it has no recognition whatsoever nor does it get them a job, leaving their future bleak,” says the Professor who is also the competition director of Dasara Kusti.

Efforts are being made to seek government support to set up a wrestling school in ‘kustigey tavaruru’ Mysuru, like the ones in other parts of the state. He along with Dasara Kusti sub committee secretary D Ravi Kumar, have been trying to revive the garadis and encourage the wrestlers to train for ‘point kusti’.

Seeing the decline in the numbers of those visiting garadis, the two gentlemen, along with a few senior wrestlers, came up with a marali ba garadige (come back to the garadi) programme, a year ago under which monthly bouts were held in different villages, and which has seen a slow revival of the tradition. “Most villages now have regular bouts of kusti. Birthdays of eminent villagers and other such events are slowly turning into occasions that feature a kusti event,” he says, optimistic about the changes. “Passion was backed by patronage in the earlier days as it was a matter of pride to back a pehelwan. The audience too was larger as it was a great source of entertainment in the rural areas,” says Kumar, who has been the secretary of the Dasara Kusti committee for 15 years now.

“Even after the era of maharajas, there was an instance, a few years back, when two bakeries in Mysuru sponsored different wrestlers in the spirit of competition. There was someone who sponsored milk for these top wrestlers. Such individual sponsorship is not feasible today, but corporates can certainly, fund these efforts,” he adds.

The government has nothing in place for a wrestler to get a job under the sports quota or to help a wrestler. “If the government can make provisions for at least some junior-level job in the police services where their training can also be put to use, it will encourage youngsters, who now have to worry about earning a livelihood,” muses the father of a wrestler, who has won many medals, but the award money ( some state funded) are still pending.

The prize money paid to the wrestlers who train so hard is less than what a pair of gym shorts would cost in a city. Most tournaments get them a silver gadha, a sash and a small cash amount, sometimes even as little as a few hundred rupees.

The bigger prizes for events of the scale of a Dasara competition ranging around Rs 10,000 to Rs 15,000 take months to reach them. This, when some of their parents are spending similar amounts per month on their food, training, trips to training schools elsewhere in the country. Tales of former wrestlers having taken to menial jobs finding it hard to make ends meet are umpteen.

How To Help Wrestling Survive

All they need, the wrestlers say, is a National Institute of Sports (NIS)-trained coach, so with their help, they can compete at the amateur levels to begin with. Kumar says that corporate sponsorship and patronage to wrestling will go a long way in changing the wrestlers’ plight.

A wrestling school with a trained coach, backed by corporates, who can also hire the services of these wrestlers for jobs that suit them, and equal recognition by the government on par with other sportsmen, would do this traditional Indic sport a great deal of good.

Until then, say these pehelwans, they will continue to throw the matti mannu on themselves and work on stone sculpting their bodies.

And here is a sneak peek at how they do it:

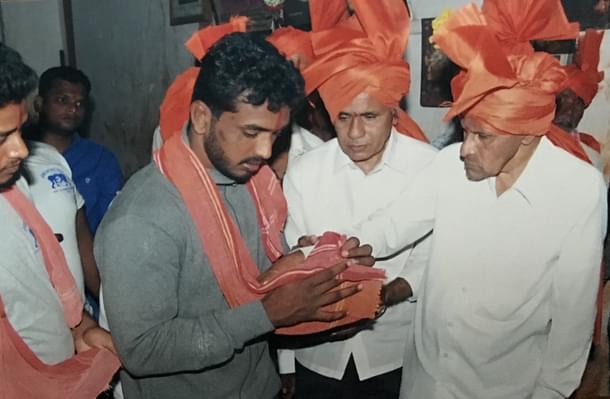

The wrestling costume or the komana which is handed over by a senior wrestler with blessings is worn by the wrestlers, who then offer puja to the idol of Hanuman, ‘the original pehelwan’. This is customary for every garadi mane.

They then take the blessings of all elders around and begin their workout with the traditional equipment. One of them then picks the guddali and sifts the dark red bed of mud, while another evens it out with his feet.

This mud is a mixture of herbal soil, mixed with turmeric, vermillion, ghee and other prescribed material that is beneficial to the body, and worshipped before they step on it. Once levelled, the wrestlers practise various techniques to pin down their opponent onto the ground, which is the only marker of victory in this form of Indic wrestling.

Harsha Bhat is an author, linguist, content strategist, and a compulsive chronicler of Bharat's civilisational heartbeat.