Defence

Explained: Why China Is Deploying Underwater Drones Near Indian Ocean Choke Points

Swarajya Staff

Jan 22, 2021, 12:27 PM | Updated 01:16 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In December last year, a group of Indonesian fishermen found a Chinese underwater Sea Wing glider drone near the country’s Selayar Island. This wasn’t the first time an underwater drone of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) had been discovered in the region — it was the fourth found in Indonesian waters in the past two years.

The discovery of these underwater drones in waters directly off the islands of Indonesia was significant not because they were found far away from China’s adjacent waters but due to their proximity to potential routes — called chokepoints — linking the South China Sea and the Pacific to the Indian Ocean.

In February 2019, a Chinese underwater drone was discovered in Indonesian waters near the northern tip of Bangka Island in the northern part of the country. In March that year, another Chinese underwater drone, labelled ‘Sea Wing’ and ‘China Shenyang Institute of Automation’ in Chinese characters, was found by an Indonesian fisherman near Riau Islands. This was followed by the discovery of another underwater drone of the PLAN lurking in Indonesian waters in December 2020 near Selayar Island.

The two Chinese underwater drones discovered in early 2019 were operating close to the Malacca and Sunda Straits, two maritime chokepoints connecting the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific and the South China Sea. The PLAN’s ‘Sea Wing’ drone found in 2020 were lurking very close to the Lombok Strait, the other potential route between the two water bodies.

The discovery of four PLAN drones in Indonesian waters in a short period of two years points to hectic Chinese activity in the area around these chokepoints, and also in the Indian Ocean, where it seeks to increase its footprint.

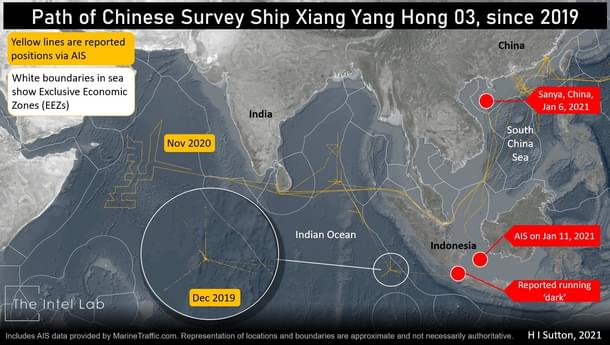

In January, only days after the discovery of the fourth underwater drone in December 2020, a Chinese survey ship was intercepted by the Indonesian Coast Guard near the Sunda Strait. The Chinese vessel, Xiang Yang Hong 03, was “running dark” or operating without an activated transponder. The Chinese survey ship, which was hiding its route and location by not broadcasting its position via the Automated Information System (AIS), was later escorted out of Indonesia’s Economic Exclusion Zone.

Indonesia requires all ships transiting the waters to have functioning AIS, and prohibits them from indulging in oceanographic research.

Xiang Yang Hong 03, the research vessel, is a regular visitor to this region. The ship has made several forays into the Indian Ocean over the last few years. It passed through the Sunda Strait (between the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra) and entered the Indian Ocean in November 2019.

In the following months, Xiang Yang Hong 03 surveyed waters west of Indonesia and in the Bay of Bengal, very close to the Indian island chain of Andaman and Nicobar. In November 2020, the Chinese research vessel was back in the Indian Ocean, this time to survey a large part of the western Indian Ocean.

In September 2019, only a month before Xiang Yang Hong 03 entered the Indian Ocean, India had expelled a Chinese research vessel from its exclusive economic zone near the Andaman and Nicobar Islands as it was operating in the area without securing requisite permission. The Indian Navy had located the suspicious vessel, identified as Shi Yan 1, in the Indian waters west of Port Blair.

While there are no restrictions on conducting marine scientific research in international waters under United Nations Convention on the Law, states are required to seek permission at least six months in advance for marine scientific research in another country’s EEZ or continental shelf.

Chinese vessels have also carried out extensive deepwater surveys in the southern Indian Ocean and around Australia’s strategically-located Christmas and Cocos Island and along the western coast of the Australian mainland.

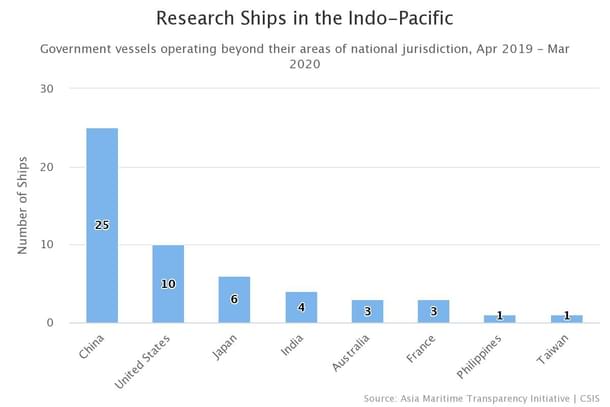

A study by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, in which state-owned or -operated survey vessels in waters beyond their government’s legal jurisdiction were tracked between April 2019 and March 2020, found that China operated “by far the largest fleet of government research vessels” in the Indo-Pacific.

While China still depends on its large fleet of survey ships for the collection of oceanographic data crucial for undersea operations, addition of underwater drones has enabled it to expand its reach not only in international waters but also territorial waters and exclusive economic zones of other countries where large, visible research vessels can’t operate without permission.

China had deployed at least 12 Sea Wing underwater drones in the Indian Ocean in 2019 using its survey ship Xiang Yang Hong 06.

“The 12 underwater gliders carried out cooperative observation in a designated sea area. Together they traveled more than 12,000 km and conducted more than 3,400 profiling observations, obtaining a large number of hydrological data...,” the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in March 2020.

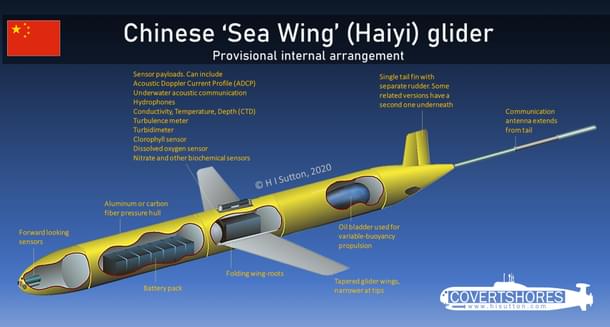

China’s torpedo-shaped underwater drones, also called Haiyi, are unpowered. Instead of using battery power, these drones use variable-buoyancy propulsion to glide in water. The drones generate forward movement by first sinking to a desirable depth and then rising. This is achieved by inflation and deflation of a balloon-like device filled with pressurised oil.

While its large glider-like wings increase the distances travelled through the sinking and rising, the small rudder is used to control direction.

The hull of the 2.2 metre-long drone carries various sensors, which use power from the battery onboard. A communication antenna which extends from the tail of the drone is used for transmission of data to the mothership or the base.

Both underwater drones and survey vessels help the PLAN collect the oceanography data critical for operations of its underwater platforms.

These platforms map the contours of the seabed, and collect data such as salinity, turbidity, chlorophyll and oxygen levels. By one account, the drone could be capable of studying the propagation of sound underwater, which “paints a picture of the acoustic and thermal environment, allowing submarines to hide under layers of thermocline to avoid sonar detection from surface warships”.

Such data can not only help China in detecting and tracking foreign submarine movements but also for planning routes which its own submarines can use for transiting through these areas while submerged.

Given that most of China’s underwater drones have been found close to the three major chokepoints which link the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, it is likely that the platforms were involved in studying submarine routes that the PLAN submarines use when going into the Indian Ocean.

“The glider would be taking sonar soundings of the ocean bottom to get an accurate bathymetric map of the sea floor, as well as using sensors to understand thermal conditions within the water, and acoustic conditions, so as to give PLAN submarines the best chance for traversing the Sunda Strait without being detected,” Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst in Chinese military modernisation at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, has said.

China's naval deployments in the Indian Ocean have been on the rise since 2008. Both conventional and nuclear submarines of the PLAN have been spotted in the region. The operational scope and geographical coverage of PLAN’s capabilities in the region is only likely to increase as the Indian Ocean becomes the centre of geopolitical competition between New Delhi and Beijing.