Defence

How China Is Building A Rail Network In Tibet To Dominate The LAC

Prakhar Gupta

Aug 31, 2025, 07:30 AM | Updated Oct 09, 2025, 09:08 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In 2021, new recruits at a combined arms brigade affiliated with the PLA Tibet Military Command boarded a gleaming Fuxing bullet train. Their destination was an exercise field at 4,500 meters above sea level, where they would undergo high-altitude training.

This was no ordinary train ride. For the first time, the newly opened Lhasa–Nyingchi Railway, part of the larger Sichuan–Tibet Railway project, was used for a military transport mission. PLA media hailed it as a milestone in the “systematic development of China’s military transport.”

What might have appeared to be a routine logistics exercise revealed a deeper strategic intent. Beijing was working to dominate the Line of Actual Control (LAC) through a network of rail lines running along the frontier.

As the train sliced across the Tibetan Plateau, carrying troops to a remote training ground, India confronted a sobering reality.

Over the past decade, India has invested billions in highways, bridges, and tunnels along the LAC, narrowing the long-standing gap in road connectivity. For decades, China held a clear advantage, with the ability to alter the status quo on the ground at will. That edge, however, had finally begun to erode as India caught up.

But Beijing’s integration of civilian high-speed rail with military mobility along the Tibetan frontier has now created an entirely new disparity.

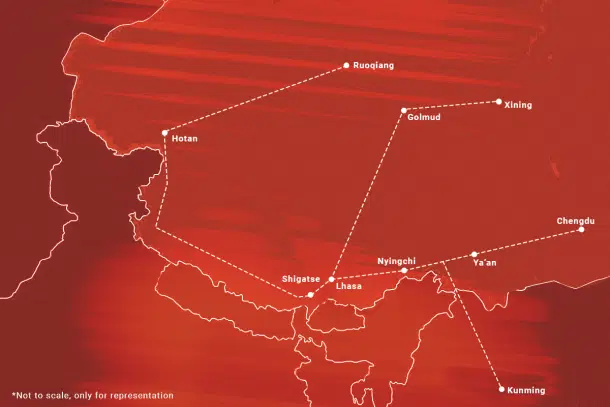

Four years later, in 2025, China has begun laying the next section of its railway network to gird the entire LAC, creating an iron backbone for military logistics that will stretch from Aksai Chin in the west to Arunachal Pradesh in the east.

Qinghai–Tibet Railway

The Qinghai–Tibet Railway, completed in 2006, was the first rail line to reach Lhasa. Running nearly 2,000 kilometres from Xining in Qinghai province to the Tibetan capital, it was the engineering marvel that made everything else possible.

The line traverses some of the harshest terrain on earth, frozen deserts, permafrost fields, and mountain passes that climb above 5,000 meters. Over half its length lies at elevations considered physiologically challenging for most human activity.

For Beijing, the project was a political and strategic triumph. For the first time, Tibet was physically bound to the Chinese heartland by rail. Civilian benefits were loudly touted, including cheaper goods, more tourism, and faster mobility for Tibetans.

But for the PLA, the significance was more immediate and enduring. The Qinghai–Tibet line gave China a bulk logistics artery into central Tibet. Golmud, a once-remote town along the line, has become a key staging post for fuel, ammunition, and troop transfers.

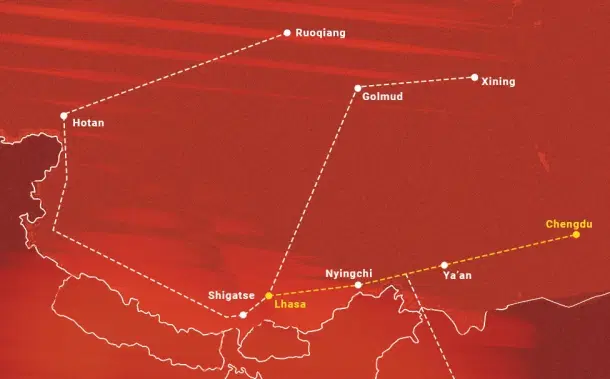

Sichuan–Tibet Railway

If the Qinghai line was about connecting Tibet to the Chinese mainland, the Sichuan–Tibet Railway is about fortifying China’s frontier opposite Arunachal.

The 1,629-kilometer line will eventually link Chengdu, headquarters of the PLA’s Western Theater Command, to Lhasa in just 13 hours.

The line is divided into three sections — Lhasa–Nyingchi, Nyingchi–Ya’an, and Ya’an–Chengdu. Work began in earnest in 2014, and by 2018 the Chengdu–Ya’an section, the shortest of the three, was operational.

Then in June 2021 came a major breakthrough, the opening of the Lhasa–Nyingchi section, a 435 km stretch that takes just three and a half hours to traverse.

It was on this line that the PLA’s recruits took their symbolic train ride in 2021. And the significance was not lost on Indian observers. The Chengdu–Lhasa railway runs close to the LAC, with Nyingchi lying just north of India’s Tuting sector in Arunachal’s Upper Siang district.

Once a modest garrison town in southeastern Tibet, Nyingchi has become a focal point for Beijing’s infrastructure push, with substantial investment aimed at linking the border city more closely to the rest of China, and to the frontier with India.

The town has a dual-use airport and a military heliport. The PLA’s 52nd and 53rd Mountain Infantry Brigades are based in the prefecture, and the infrastructure, with the rail line being the latest addition, gives them unprecedented logistical depth.

The completion of the 409-km Lhasa–Nyingchi Expressway in 2017 had already reduced travel time between the two cities from approximately eight hours to about five hours.

China has also built a new network of roads and tunnels linking Nyingchi with Medog, a remote area right at the China-India border. The project reduced the distance between the two from 346 km to 180 km, and slashed travel time by about eight hours.

Nyingchi has drawn attention from the highest echelons of the Chinese Communist Party in recent years, with apparatchiks often stressing the military utility of the infrastructure being built in the region, especially the railway.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, on his first visit to Tibet as head of state in 2021, landed at Nyingchi Mainling Airport, not far from the LAC, before boarding a train on the newly inaugurated Lhasa–Nyingchi railway to reach the Tibetan capital.

"Xi went to Nyingchi railway station, learning about the overall design of the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, and then took the train to Lhasa. He inspected the construction along the railway during the ride," Chinese state media had reported at the time.

The train journey took just a little more than three hours, a dramatic improvement from 1998, when Xi, then serving as deputy secretary of the Communist Party in Fujian Province in east China, had made the same journey by bus, spending an entire day navigating difficult mountain roads.

"The roads were extremely dangerous back then," Xi recalled during this 2021 visit, adding, "We were lucky that there were no landslides. In the narrowest spots, just two logs spanned the gap, and we had to get out and move them ourselves."

In July this year, it was from Nyingchi city that Chinese Premier Li Qiang announced the start of the construction of a mega-dam, a $167.8 billion hydropower project, in the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo river, or Brahmaputra, as it is called in India.

By 2030, when the central Ya’an–Nyingchi section, the longest of the three at 1,011 km is complete, the line will give China a direct military artery from the Sichuan basin to the Himalayan frontier opposite Arunachal .

CCP officials, as Swarajya has reported earlier, have publicly recognised that the new railway will enhance China’s ability to move troops and equipment.

Zhu Weiqun, a senior Communist Party official who once oversaw Tibet policy and led a series of negotiations with the Dalai Lama’s representatives between 2002 and 2010, has remarked, “If a scenario of a crisis happens at the border, the railway can act as a ‘fast track’ for the delivery of strategic materials."

For India, the prospect is unsettling. Troops could be loaded in Chengdu in the morning and be in Nyingchi by nightfall, supplied by trains carrying tanks, artillery, and missiles.

Lhasa-Shigatse Rail Line

While the Lhasa–Nyingchi section extends eastwards towards Arunachal and further connects to Chengdu, the Lhasa–Shigatse railway runs westwards, towards Sikkim, linking Lhasa with Tibet’s second-largest city and opening direct access to southwestern part of the border.

The line not only improves connectivity to Shigatse itself but also provides enhanced access to the Chumbi Valley (called Yadong by the Chinese) , the corridor between Sikkim and Bhutan, and the Doklam plateau, an area that remains a sensitive flashpoint between India and China.

The Lhasa–Shigatse line is also slated to integrate with future expansions from Xinjiang, forming the western segment of China’s broader Tibet railway network. Once completed, the planned Xinjiang–Lhasa line will feed into Shigatse, allowing rapid movement of personnel and equipment across the plateau from the northwest.

Plans are underway to extend the Shigatse line westward to Gyirong, a key trading town near the Nepal border, establishing a corridor that links Tibet with Nepal and improves lateral mobility for PLA units across southwestern Tibet. This extension may now be integrated as part of the broader Xinjiang–Tibet railway project.

Separately, there are proposals to extend the railway southward to the town of Yatung in Chumbi Valley, although progress on this section has been slow.

Yatung lies near the Nathu La pass, which connects Tibet to Sikkim. Western Bhutan, where China claims the Doklam plateau, sits just across the Chumbi Valley. It was through this valley that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru traveled on his way to Bhutan in 1958.

In a letter to the Chief Ministers written during the journey, Nehru noted—perhaps surprisingly—that roads on the Indian side were better than those in Tibet, a striking contrast to the infrastructure disparity that later emerged as successive Congress governments deliberately left India’s border areas underdeveloped.

"At the top of the Nathu La ended the road that our engineers had constructed, and on the other side we had to descend by precipitous bridle paths. This road on our side is a remarkable feat for which our engineers deserve great credit," Nehru wrote.

"If a road could be built on the other side of the Pass, connecting Yatung, then there would be through road communications between India and Tibet. On the Tibetan side this road will be a much simpler proposition than the one that we have built on our side," he added.

What makes Nehru’s observation even more startling is that by then, the Chinese had already finished building the 2,340-km-long Xinjiang–Tibet highway (G219) through Aksai Chin, and that Indian officials had been reporting the development since at least 1955.

The road quietly laid the foundation for Beijing’s enduring infrastructure advantage, enabling its swift thrust into India in 1962 and supporting a steady buildup of roads, airstrips and garrisons all along the frontier over the next few decades.

It is through the Xinjiang–Tibet highway and the network of roads and airfields that have sprung up along it that men and materials for the construction of the Xinjiang–Tibet rail line will now begin to pour in along the LAC.

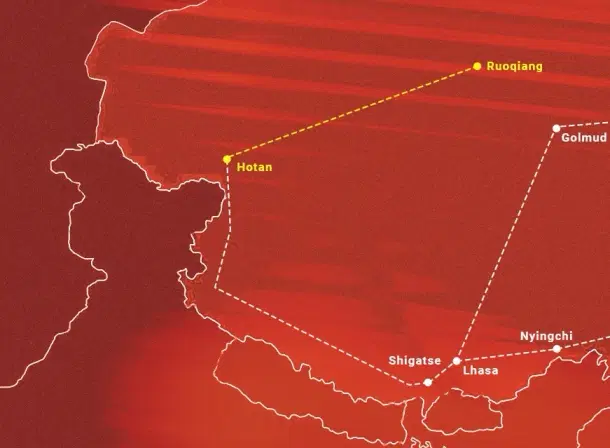

Xinjiang–Tibet Railway

If the Xinjiang–Tibet highway quietly gave China its first decisive infrastructure edge over India in the 1950s, the Xinjiang–Tibet Railway now promises to replicate, and vastly amplify, that advantage. Running broadly along the same corridor as G219, the railway will transform what was once a precarious road lifeline into a high-capacity artery, giving the PLA the same mobility that the highway enabled in 1957, but on a scale that can alter the entire balance of logistics on the plateau.

At nearly 2,000 km, the railway will link Hotan in Xinjiang with Shigatse and Lhasa in Tibet, with the Shigatse–Pakhuktso section expected to open by 2025 and the full line completed by 2035. Backed by 95 billion yuan (around US $13.2 billion) in capital through a newly formed Xinjiang–Tibet Railway Company, the project is part of Beijing’s wider plan to create a 5,000 km rail grid radiating out of Lhasa by the same date.

The line will link a string of towns along the LAC that today host large PLA bases. One such town is Rutog, located just west of the Pangong Lake. It already functions as a key staging post connected by the G219, from which a network of feeder roads snakes towards the LAC and provides last-mile connectivity to forward positions. The base at Rutog was a key launchpad for PLA mobilisations during the 2020 border standoff with India

Once linked by rail, the base will no longer be dependent only on long, slow, and vulnerable road convoys. Instead, it will be transformed into a rail-powered logistics hub capable of sustaining forward deployments with far greater speed and scale.

Hotan–Ruoqiang Railway

While the Sichuan–Tibet line secures China’s eastern approach, the Hotan–Ruoqiang Railway, completed in June 2022, consolidates its western flank.

Stretching 825 kilometers across southern Xinjiang, the line connects Hotan to Ruoqiang. At first glance, this may appear to be a regional development project. In reality, it is a major logistical enabler for military operations in Aksai Chin and Ladakh.

The rail line has slashed travel time between Hotan and Xining, the capital of Qinghai, from three days to just one. With Hotan and Golmud already established as a key logistics and military hubs, the Hotan–Ruoqiang line created a fast-moving corridor for the PLA to surge men and materiel into northwestern Tibet .From here, forces can move via the Xinjiang–Tibet Highway into Aksai Chin and beyond.

A Network Takes Shape

Individually, each of these rail lines can be justified by Beijing as economic development for Tibet and Xinjiang. Taken together, they form something far more significant, a military transport grid designed to help the PLA dominate the LAC.

This grid ties Tibet irrevocably to the Chinese mainland, while simultaneously giving the PLA lateral mobility across the plateau.

The PLA now has three axes of entry into Tibet: one from the north via the Qinghai–Tibet railway line, a second from the east via the Sichuan–Tibet railway line, and a third from the west via the Hotan–Ruoqiang railway line.

The Xinjiang–Tibet railway, once built, will connect all three axes, with each feeding into it from different directions, enabling the PLA to reach bases all along the frontier with India. It will give China an unbroken railway corridor along the entirety of its contested border with India

For India, the contrast is stark. Rail connectivity in Arunachal only began in 2014. Projects like the Bhalukpong–Tawang line and the Bilaspur–Leh line remain years behind, and perhaps decades away from operationalisation. Roads have improved, and tunnels have been completed, but the sheer capacity gap remains daunting. A single Chinese train can carry the equivalent of dozens of Indian truck convoys.

The geographic contrast further compounds the imbalance. While much of the Tibetan Plateau on the Chinese side consists of relatively broad valleys and plateaus that allow for high-capacity rail and road construction, the Indian side of the LAC is far more rugged. Steep mountains, narrow valleys, and unstable slopes make infrastructure projects slower, more expensive, and technically challenging.

Even where roads exist, they often require lengthy detours and are vulnerable to landslides and snowfall, limiting the speed and volume of troop and equipment movement compared with the PLA’s rail-enabled mobility.

In any future crisis, this disparity will translate directly into military advantage.

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.