Economics

Holding Up Half The Sky: Improving Women’s Higher Education Is Key To India Becoming A $10 Trillion Economy

TV Mohandas Pai and Nisha Holla

Jun 13, 2019, 06:11 PM | Updated 06:11 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The National Fertility and Health Survey-4 shows that India’s fertility rates have dramatically dropped to 2.18, below replacement rate. Demographics are changing across the socio-religious spectrum and are strongly correlated with women’s education and literacy. In this article, we look at women’s progress in higher education to further understand this demographic change.

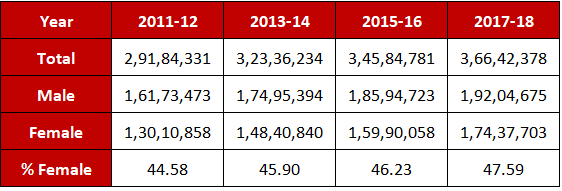

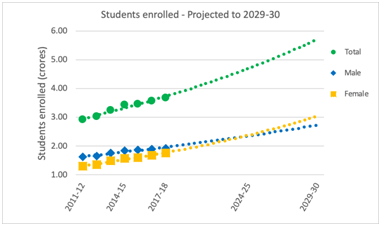

Higher education statistics published by AISHE, MHRD (Table 1) from 2011-12 to 2017-18 shows an increasing trend. Total number of males enrolled increased by 30.3 lakhs, 18.7 per cent in 6 years, while the number of women enrolled increased by 44.3 lakhs, a whopping 34 per cent rise. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for total enrollment is 3.87 per cent, with males at 2.9 per cent and females at 5 per cent. The percentage of women rose from 44.6 per cent in 2011-12 to 47.6 per cent in 2017-18. More women are pursuing higher education now than ever before.

Extrapolating the data out to 2030 (Fig 1) indicates the number of women pursuing higher education might soon exceed men. 2024-25 could see a normalization between genders, and 2029-30 could see as much as 53 per cent enrollment of women, a dramatic shift. Many countries around the world have undergone this. In the United States, according to official statistics, 56 per cent of undergraduates are women. India is following this trend.

The silent revolution

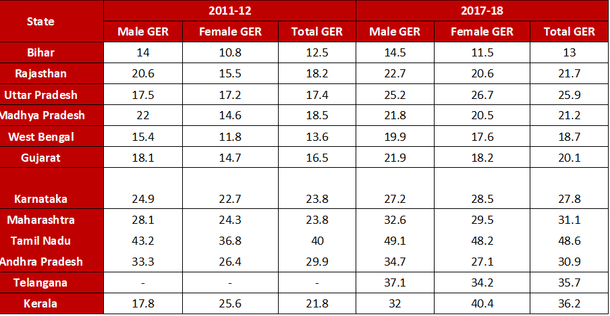

The total Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) in age 18-23 is steadily increasing from 20.8 in 2011-12 to 25.8 in 2017-18 (Table 2). Male enrollment increased from GER of 22.1 to 26.3, a 19 per cent increase. Female enrollment rose even faster, with a GER under 20 to 25.4, a significant jump of 30 per cent. The GER between genders is normalizing, again indicating that more women are turning towards higher education to improve their livelihood.

These trends show a silent revolution over the last decade, with significant implications on fertility rates and the economy. It would seem that as more women are turning towards higher education and correspondingly better employment opportunities, they are delaying childbirth and having fewer children. Higher education is one of the contributors to the levelling off of population growth.

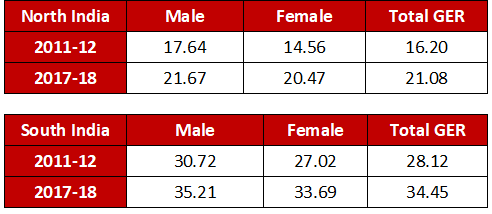

With India’s 29 states having diverse economic conditions, variance in state-wise GER is huge. Table 3(a) contains GER of representative states in North and South India for 2011-12 and 2017-18.

On an average, North Indian states have much lower GER compared to South, and the divergence is increasing. GER also correlates with development — Bihar’s GER moved nominally by 0.5 in six years and also trails in development metrics.

The population-weighted averages of representative North and South Indian states are computed in Table 3(b).

Significant observations are:

- Both the North and South GER have progressed significantly in the last decade. North Indian states have progressed by 4.88 points and South Indian states by 6.33 points from 2011-12 to 2017-18.

- The difference between the Northern and Southern states of India is striking. On average, the GER of South Indian states is ahead of the North Indian states by 13.37 points in 2017-18.

- Women are progressing faster than men. In North India, the average female GER jumped 5.91 points from 2011-12 to 2017-18, whereas the male GER moved 4.03 points. In South India, the female GER jumped 6.67 points whereas the male GER moved 4.49 points.

Financial status of Indian women has dramatically increased

At the time of Independence, policymakers did not focus on educating women. As a result, household income and India’s GDP did not grow as much as it could have. Contrast this with China — with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Chairman Mao famously said, ‘Women hold up half the sky,’ and instituted strict policies to educate women. The result is evident today in the women’s workforce participation and contribution to China’s GDP and its outstanding rise as a ‘Top 2’ economy.

With Indian women pursuing higher education in larger numbers, they must be empowered to contribute to the nation’s growth. It is opportune for India to leverage this economic multiplier to its GDP as it sets the course to achieve the $10 trillion mark.

Quality employment opportunities is the need of the hour

The need of the hour today is to provide the educated population with quality employment prospects. These must include incentives for participation of women in the workforce. Many women in India are primary caregivers of their children and other family members. Employment policies must take these aspects into consideration so that women can have the flexibility to work around their schedules. Otherwise, well-educated women will have no option but to drop out of the workforce, which will be a loss for everyone — from the individual, to her family, to the nation.

Fertility survey data indicates there will be fewer young people twenty years from now. This will result in India’s workforce shrinking rapidly while supporting an ageing population. If more women are incentivized to work, they will contribute to society and the GDP for a long time, especially given that Indian lifespans and general well-being are also increasing.

Policy can also examine which fields women are pursuing more and focus on retention there. AISHE data shows that for the first time in 2017-18, enrollment in M.B.B.S. had more women — 50.3 per cent — than men. If workforce participation of women doctors is improved through policy, this could transform India’s healthcare system.

Are women in India overtaking men?

The next pertinent question is, ‘are women in India overtaking men?’ and how to deal with this. In South India, educational institutions are resorting to interesting ways of handling the inversion. For example, some pre-university colleges in Bangalore are applying a higher cut-off percentage for women applicants. While this might not be the fairest way, we certainly see a possibility of a ceiling — say 60 per cent — imposed on women enrollment.

The data from the AISHE and NFHS surveys indicate that the best investment India can make towards economic prosperity and societal progress is in higher education and employment prospects for women.

TV Mohandas Pai is Chairman, 3one4 Capital, and Nisha Holla is Research Fellow, 3one4 Capital