Economics

Urban poverty – some myths and a reality check

Muthuraman

Jun 16, 2014, 01:17 AM | Updated Apr 29, 2016, 12:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

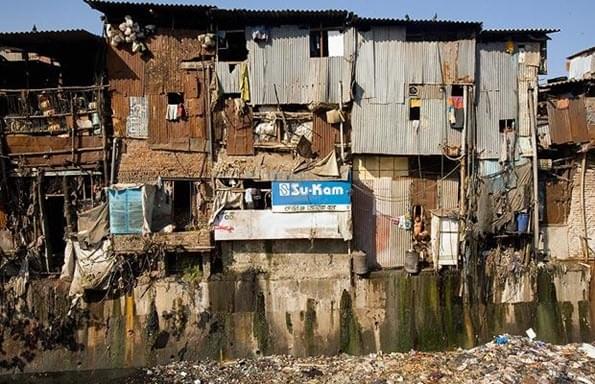

Urban Poverty: Myth and Reality

There are no involuntary poor people in India’s urban areas; if someone in urban areas remains poor today, it is on his or her own choosing! This may sound harsh and cruel, and may be in sharp contrast to what we see on the roads and slums spread across every city in the country. But please indulge me while I attempt to prove this statement with facts and figures.

Poverty Definition

Before we proceed, let us get to the basic definition of poverty. The much-derided Montek Singh Ahluwalia’s Planning Commission definition of Rs. 32 per person per day (which works out to Rs. 4800 per month for family of 5) is NOT the benchmark I intend to use here. Let us take double of that, and define that a family that earns less than Rs. 10,000 per month shall be defined as living in “abject poverty”.

This does not mean that anyone earning Rs. 10,001 per month is “rich” or “middle class” by any stretch of imagination! But one could come to a reasonable conclusion that a family that earns Rs. 10,000 p.m. is not living in abject poverty and, under normal circumstances, can be classified as having “basic sustenance” livelihood.

This definition is important because government policy measures for those in “abject poverty” are very different (provide free food, public shelter, etc.) than for those in “basic sustenance” category (quality education, quality healthcare, affordable public transport, etc.).

Here is an attempt to portray a typical monthly budget for a family of five, which can be categorized as “basic sustenance” livelihood:

| Rice/Wheat | 1000 | 25 kg per month, @ Rs. 40 per kg |

| Pulses | 1050 | 50g per meal per person; 70 per kg Tur, urad, moong, masoor |

| Vegetables | 750 | 100g per meal per person; 25 per kg |

| Oil | 480 | 3 kg per month |

| Electricity | 240 | 3 fan, 3 light for 8 hours + 1 mixie/grinder @Rs. 3.00 per unit |

| LPG | 375 | A gas cylinder is assumed to last 40 days |

| Transport | 900 | 15 Rs. Per adult per day |

| Rent | 2000 | Single bedroom in sub-urban areas |

| Schooling | 1200 | Rs. 600 p.m. for two children |

| Healthcare | 500 | Health insurance for a family of five costs Rs. 6000 per annum |

| Mobile Phone | 100 | Basic pre-paid mobile; current ARPU is less than this. |

| Others | 905 | Monthly provisions like soap, paste, etc. and annual like clothing, footwear, etc. |

| Savings | 500 | |

| TOTAL | 10000 |

|

Few important things to note here:

- None of the above costs are “subsidized” by the government and is as per prevailing market rates

- Capital asset purchase costs (mainly household assets) are not provided here. It is assumed that savings over a period of time could be used for such purchases.

- Needless to say, the quality of life here is not easy without any allowance for entertainment, travel, exigencies, etc. But the point is to address whether this income level reflects “abject poverty” (like living on the streets and taking to alms for feeding), or this reflects a basic sustenance level livelihood, though with lot of scope for improvement. I am sure most will agree that this reflects the latter.

Urban Income levels

Having established a basic watermark for poverty which is well above the official definition, let us focus on the current income levels of various professions in URBAN areas:

- A plumber, carpenter, electrician or painter charges about Rs. 700 per day of work (qualified/experienced ones charge Rs. 1000 per day). This works out to Rs. 17000 per month, for 25 working days. The skills required for this can be classified as “moderate”.

- An auto driver earns (net of fuel expenses and vehicle rent) about Rs. 750 – 1000 per day of work. A regular driver at office or residence charges Rs. 12000 – 13000 per month (excluding overtime/bonus etc.). The skills required for this is just basic driving knowledge. More experienced drivers with minimum English speaking ability can earn significantly higher monthly incomes.

- Several SME entrepreneurs in manufacturing industry complain about lack of availability of labour – both skilled and unskilled – despite offering Rs 500 per day (for unskilled) or Rs. 10-12000 per month for semi-skilled labour. The problem is much more acute in case of construction companies, where lack of labour availability has stalled several projects or has resulted in significant cost and time over-runs.

- Restaurant owners today face significant labour shortage. As per industry veterans, until 10 years ago, migrant workers from neighbouring states moved in for such work. In the last few years, migrant workers from Bihar and UP who used to fill in the demand-supply gap have also stopped; today most restaurateurs rely almost entirely on migrant workers from North East. And one quipped “the day is not very far off when I have to bring migrant workers from Philippines or Indonesia to meet our labour demand”! And the salary levels start from Rs. 9000 per month, plus food and accommodation.

- More examples follow:

- Iron (press) person : Rs. 700-1000 /day (Rs. 4-5 per cloth, 150-200 cloth per day)

- Courier delivery : Rs. 10000 per month

- Cook : Rs. 4-5000 per month (per house for 3 hours)

- Maid : Rs. 2-2500 per month (per house for 1.5 hours)

- Vegetable vendor : Rs. 500-800 per day (net earning)

- The less skilled workers are construction labourers (helpers /manual labour) who can earn around Rs. 250-300 per day. The least skilled of all, a watchman, typically earns about Rs. 5-6000 per month. Even here, a family of two adults would bring home more than Rs. 10000 – 12000 per month.

Each of the above professions falls under unskilled or semi-skilled labour and there is tremendous shortage of labour in almost all of these categories. There could be few pockets of distortion in labour markets, where labour could be available at lesser rates than mentioned above; but I believe those are most likely to be an aberration than the rule, which will get corrected soon, in the absence of any externality (such as bonded labour, child labour, etc.).

Exceptions

A natural question that comes to an inquiring mind is this: Despite such shortage of labour and decent sustainable income levels, why do we see so much squalor all around us in urban areas? Why are there so many beggars outside temples and in traffic signals? The reasons can broadly be summarized in the following categories:

- Broken / dysfunctional families: Single mothers, orphaned children, very large families with fewer wage earners (though usually rare in urban context), etc. can skew any of the estimations above, pushing such people to abject poverty levels.

- Voluntary unemployment: Though sounding harsh, this is a reality in many instances where able-bodied young men and women prefer to remain unemployed voluntarily, either due to mismatch in expectations vis-à-vis availability of jobs, or simply due to lack of interest.

- Excessive drinking: This is a grievous problem, magnitude of which is increasing by the day! Any amount of income will not be sufficient if disproportionate level of income is spent on alcohol rather than in upbringing of the family.

- Poor Health / Disability: Physical or mental disability, poor health of earning members of the family, accident, etc. can, and often does, push families into abject poverty.

While some of these could be addressed through appropriate policy interventions (such as a safety net) by the government, these are more likely to be “exceptions” in the larger scheme of things or beyond the purview of the Government of the day (e.g. Point 2 and 3 above). A clear understanding of this reality could help shape appropriate public policies that suit the current populace and its aspirations, rather than the worn out “gharibi hatao” era doles and freebies.

Implications for Public Policy

The motivation for this column is not to deprive anyone of the little support that they get from Government to help their ends meet. Rather, it is the desire to see that the scarce government resources are allocated in an efficient manner.

Targeted schemes for those living in abject poverty (akin to Antyodaya Anna Yojana of Vajpayee Government that targets ‘poorest of the poor’) and using the rest of the resources for skill development and urban infrastructure – water supply, sanitation, power, roads, ports, airports and other infrastructure, is likely to improve the lot of the common man much faster and in a more sustainable manner, rather than giving colour televisions, mixies, grinders, table fans, etc. indiscriminately to even rich and middle class.

Even basic social infrastructure such as Education and Healthcare can be provided at affordable cost and of acceptable quality, if private sector is co-opted with Government initiatives. A public insurance model (like Arogyasri) and school vouchers, with free / minimum pricing structure can address both those below poverty line as well as those barely above this line. As has been observed earlier, the families that fall above the ‘basic sustenance’ income can afford and are already availing at the first given opportunity, such services from private sector.

At the end of the day, excessive “support” by the government indiscriminately to all sections of society is more likely to cause a moral hazard of dis-incentivising hard work and also deprive government of resources to address basic needs such as water and sanitation.

Based on the evidence available, it is reasonable to conclude that there is no “widespread abject poverty in urban areas”; greater focus should be to address widespread poverty in rural areas and restrict role of government in urban areas to providing basic physical and social infrastructure.

N Muthuraman runs Riverbridge, a boutique investment banking firm. He was formerly the director of ratings at CRISIL, India’s premier ratings firm