Economy

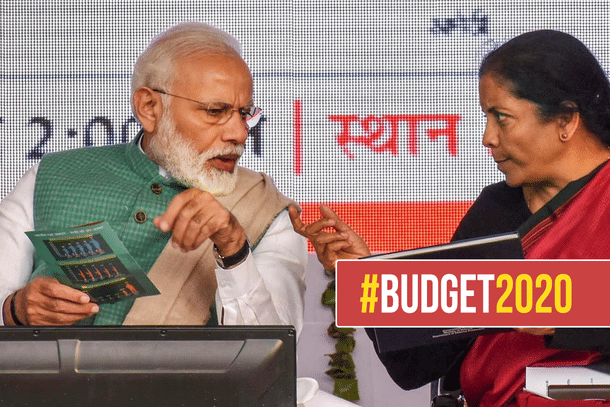

Budget 2020: A Look At The Fine Print Reveals Why Tweak In The Tax Regime Is A Much-Needed Change

Karan Bhasin

Feb 03, 2020, 05:36 PM | Updated 05:39 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

This budget has been a roller-coaster ride as I’ve found my views change dramatically on the budget and especially the tax proposals. These changes have occurred primarily due to a finer look at things and evaluating what the proposed tax changes mean for the Indian economy.

The budget, outside the tax proposals, is indeed an A-starrer as it has everything that was, perhaps, needed at this juncture, which includes resetting of the fiscal clock, some privatization and a big-ticket disinvestment.

Yet, there is a lot of noise surrounding the tax proposals and this makes it important to look at what has been done in order to decipher its implications.

Such a process frequently takes time and, perhaps, that’s why I reserved a detailed commentary on the budget. The sheer size of the document did warrant a scrutiny before one makes any comments on the same.

The decision to look at the fine print was a good one as many have ignored the set of 50 exemptions that continue to remain in the new taxation regime, for now.

One of the reasons behind the delay in writing on the taxation part of the budget was precisely the need to understand the rationale behind it.

But first, let us recognise the fact that India does tax its rich at an exceptionally high rate – and that these rates were marginally increased in the previous budget.

It is also an issue for compliance that there is a 17 per cent difference between the peak income tax rate and a corporate tax rate of 25 per cent.

Moreover, despite such high rates of taxation, the rich aren’t provided the kind of provisioning of social security that is available is several other countries.

In an article post the previous budget, Rajeev Mantri had provided a strong argument of how such taxes can harm the knowledge economy.

A similar point has been reiterated by Harsh Gupta over the last couple of months. I agree with these concerns and am sympathetic for the need for reduction in the peak rates of taxes, which will improve compliance.

Indeed, that was the justification for the corporate tax cuts and the argument holds true in general.

However, a bulk of economics and policymaking is about trade-offs, managing which often, are a combination of an art and science. In some sense, the budget tried to manage these trade-offs by partial implementation of some key recommendations of the Direct Tax Code.

One of the recommendations of the Arbind Modi DTC report that was leaked in Business Standard was the removal of exemptions to simplify our tax structure.

Removal of exemptions is indeed a tough move, considering how it impacts the mutual funds and insurance industries that have their business model built around these tax deductions.

These exemptions had made the tax system too complicated and ensured that the effective tax rate varied depending on the use of exemptions even for those who had the same income.

While many believe that section 80C, 80D, HLA or HRA are important, they must recognise that the new taxation regime is based on the principle of creating a simplified, lower tax regime that removes complexity.

In many cases and especially for those that don’t take benefit of HLA or HRA, the new rates could result in actual savings and many might want to opt for the same.

Removal of exemptions was indeed one of the more difficult recommendations of the DTC report and one must truly appreciate the government for recognising the need for taxation reforms.

Sure, the tax slabs are too narrow and there are nearly double the tax rates than what we would eventually like.

However, keep in mind that the changes in this budget comes with the backdrop of an economic slowdown and revenue shortfalls.

Therefore, the first priority was on ensuring a revival of economic activity, which brings us to the issue of a trade-off.

The government could have decided to invest in infrastructure or give a bigger tax cut or, maybe, even stuck with its fiscal targets in the hope of a cyclical recovery.

It would appear that the government was guided by the principle of taking measures that could balance infrastructure spending along with tax cuts at the bottom of the income distribution with the idea that this may have a greater multiplier which can benefit the economy in the short run.

Indeed, once growth recovers and our revenues are stabilised, we may have the necessary space to be aggressive on tax reforms.

Many believe that the tax system has become more complicated with this tweak, as individual taxpayers will have to chose whether to go with the old or the new tax regime.

However, this choice is important as it makes it possible for a gradual move towards further implementation of the DTC, which seems to be on the cards in the foreseeable future.

A key thing to remember is that abrupt tax changes can have unintended consequences too, which is why the choice of whether to continue with exemptions or not is an important one as many have already done their tax planning and availed home loans etc.

The reason for such tax planning is precisely why the choice to continue in old and new regime was retained for both Corporate and Personal Income Tax.

Considering the fiscal constraints and growth challenges, the budget seems to be based out of a calculated procedure that aims at optimizing the impact on revival of growth while sticking to the maximum fiscal room that was allowed by the FRBM.