Economy

India's Megacities: Can Centralisation Help?

Sanjeev Ahluwalia

Nov 18, 2014, 12:27 AM | Updated Feb 24, 2016, 04:16 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

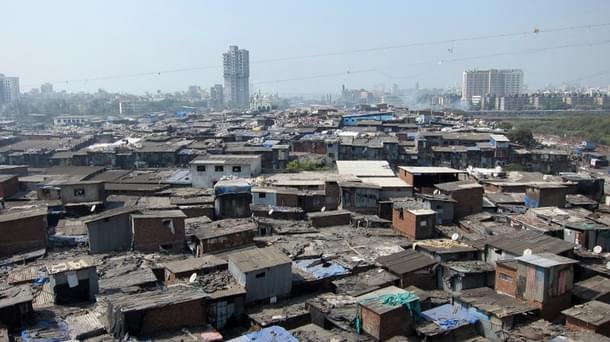

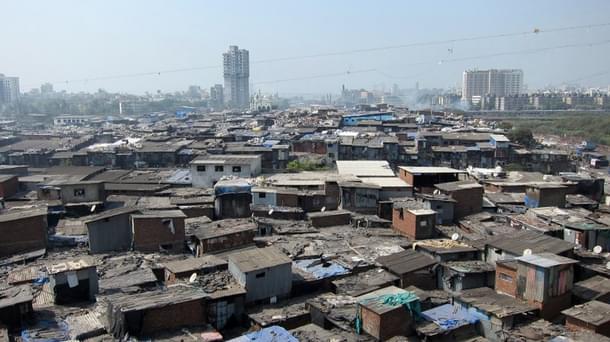

How can we get out of the perplexingly happy co-existence of some of the finest hotels and monuments in the world with the largest slum populations? The answer may be political.

First time visitors to India are usually taken aback by our degraded cities and the seeming public apathy to sewage and garbage competing for space with Bentleys and Porches—much like puberty, when it is as challenging to hide the pimples as it is to dress smart.

Ed Glasser of Harvard University, speaking at the LSE-NIUA Urban Age Conference in New Delhi a few days ago illustrated the dire situation by using the metric of vertical plus horizontal living space available per person. India’s low-rise cities squeeze people much closer together—often to suffocatingly high levels—as compared to high-rise cities with a similar spatial (horizontal) density.

The perplexingly happy co-existence of some of the finest hotels and monuments in the world with the largest slum populations has multiple explanations.

Some trace institutionalized urban neglect to the Mahatma’s vision of a happy India as comprising only self-sufficient villages with cities as necessary evils.

Others point to the stratified Hindu caste system as the reason why spotlessly clean households and well-scrubbed people have no qualms about chucking their filth into the streets. That is, the central concept of “ritual pollution” is a purely personal one. Public filth is a public issue and it is enough to be personally clean.

Urban government “groupies” identify the extended atrophy of municipal government in independent India as the key reason for listless municipal governance today.

Possibly there is a little bit of truth in all these explanations and some more. But none of them are helpful in solving the problem.

The Mahatma and his thoughts have long been relegated to the realm of our “glorious past” with little salience in a rapidly growing open economy. Spinning one’s own yarn and milking one’s own goat, even if one is a rocket scientist, negates the central concept of “comparative advantage” on which international trade is based.

The caste system has not stopped us from a low-cost space mission to Mars, from becoming the information technology back office for the West, from producing more films in Bollywood than another country in the world, and becoming the most successful, largest and most diversified democracy. Blaming urban decay on caste is just plain lazy thinking.

As outdated are those who mourn the relatively light touch of municipal government in India and the overwhelming influence of higher levels of government at the provincial and national levels.

At the same conference, T.S. Panwar, deputy mayor of Shimla, illustrated the helplessness of municipal government by calling himself the “garbage man”, since that is the only unique function his municipality could legitimately claim. Of course, one may well ask why small municipal governments need autonomy beyond the functions best performed at the local levels, like garbage management, street lighting and the maintenance of demographic records.

In this vein, Harvard University professor Neil Brenner posits that municipal autonomy, as an explanatory variable for citizen satisfaction, in an increasingly networked world, is pretty meaningless. When even nations face the prospect of losing sovereignty in monetary policy; resource use and trade policy, it is too late to target greater devolution of powers to municipalities, as a driver of high urban growth.

India’s ambition for urban-led growth has to be based on the consensual transfer of resources which fuel growth, from their existing owners to cities.

Far from devolving powers downwards, this means looking upwards to supra-municipal jurisdictions where meaningful negotiations can be done between rural constituencies, like sugarcane and rice farmers who use water wastefully today and cities who should be willing to pay for incremental water. Similarly, cities need to negotiate with the owners of agricultural land to buy land for growth at market rates. Meanwhile, city dwellers have to boost city revenues by paying higher taxes and “user charges” for the privilege of staying in a high-growth area where jobs are plentiful and the quality-of-life indicators higher.

Gerald Frug of Harvard University has a similar vision in which metropolitan conclaves, comprising representatives of all municipalities, decide how people should live in cities and are empowered by their collective size and reach to negotiate with national and provincial governments.

Richard Sennet of the LSE and NYU advises that while starting the 100 Smart City programme, to be careful to avoid creating “stranded assets” financed by public funds, as in China. The downside of fast, lumpy investments is that what once looked like a good idea very quickly gets sidelined by technological change, shifts in business cycles and evolving trade regimes.

How can India grow beyond its urban adolescence? Some lessons are relevant.

First, for all large projects, ensure that public money only leverages private investment rather than being the sole source of funding. Public resource allocation methodologies are famously inefficient. The willingness of private entrepreneurs to risk their capital by co-funding public projects becomes a plausible proxy for sound investment decisions.

Second, whilst Public Private Partnerships are consequently the chosen instrumentality for lumpy investments, both the benefits and the risks must be equitably shared between the public and the entrepreneur. Arun Nanda of Mahindra Lifespace hits the nail on the head, by stipulating that successful Public Private Partnerships never forget to ensure quantum benefits for the community they dispossess of resources.

Third, while it is true that there can be no governance without an effective government, it is unwise to equate decisive governments with good governance. Good governance implies embedded systems for “direct participation” by all stakeholders to hold government accountable.

Within the good governance ecosystem, the role of political parties is the least discussed and is the most deficient. China’s rapid urban development is as much due to single-party rule as it is to inner-party discipline. Democratic plurality is meaningless without well-administered political parties which reflect democratic ideals and public accountability in their internal processes.

The helplessness of even well-meaning politicians lower down the food chain, in the face of low traction with party bosses to solve their local problems, often reflects the top-down, stratified architecture of political parties, where “lateral entry” at the top level is the norm and meritocratic selection from within party cadres an oddity. We need more efficient and transparent vertically integrated party structures for good urban governance.

Sanjeev Ahluwalia is Advisor, Observer Research Foundation. He specializes in economic governance and institutional development.