Economy

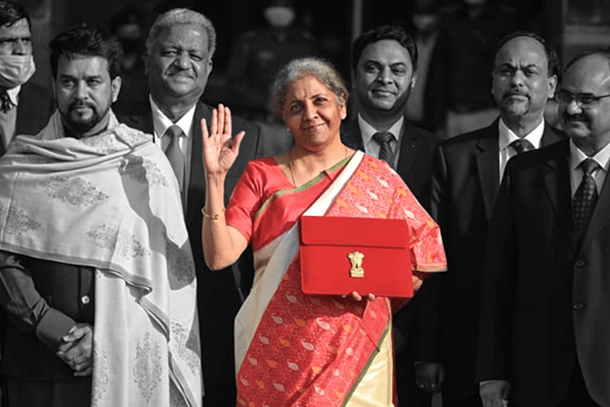

Jai Sitha Raman. Why Finance Minister’s Third Budget Is Perhaps The Modi Government’s Best Yet

R Jagannathan

Feb 01, 2021, 05:42 PM | Updated 05:42 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Many things will be said about Nirmala Sitharaman’s third budget, a budget to revive the post-Covid economy. But the one thing it clearly testifies to is this: she has broken the Narendra Modi government’s tendency towards fiscal conservatism.

Finally, we have a truly growth-oriented budget, and many shibboleths of the past have been laid to rest.

We saw glimpses of that in the Economic Survey too. The Chief Economic Adviser not only called for most counter-cyclical fiscal spending, but also rubbished our excessive focus on pleasing biased global rating agencies.

Perhaps, for the first time ever, the survey’s writers and the Finance Minister have been on the same page.

Earlier, the surveys used to mutter darkly about priorities and reforms while the budgets went their own way. Not this time. Which is why bulls jumped over the moon, with the Sensex up over 2,300 points, or 5 per cent in one trading day.

Here are some of the big takeouts of this budget.

This is a fairly honest budget, in that the fiscal deficit numbers do not look dodgy, where actual government borrowings are hidden in the books of government-owned companies like Food Corporation of India.

Perhaps, the Finance Minister decided to make a virtue of necessity by using the extraordinary situation of the pandemic to bring back all the extra-budgetary borrowings of the past into the budget math.

This is why the fiscal deficit number is a high 9.5 per cent for 2020-21 instead of the expected 7-7.7 per cent.

Next year, it will be sharply lower at 6.8 per cent without any spending cuts, which implies that this time the growing denominator (GDP) will shrink the share of the deficit. Clever, and yet honest. Resonates with the survey’s claim that it is sustainable growth that will keep debt sustainable, and not vice-versa.

Second, despite the pushback against reforms, especially in the farm sector, the budget commits the government to not only move ahead with the privatisation of companies already put on the block (Bharat Petroleum, Air India, Shipping Corporation, Concor, etc), but adding two banks and one general insurance company to the list.

You can be sure that financial sector unions will put up a stiff political fight to prevent this, and they could get backing from the likes of Rahul Gandhi, who has said that the government is selling the family silver to Modi’s cronies.

The ‘P’ word has, for the first time, been embraced wholeheartedly by a government. The bank and insurance nationalisation acts will need amending, and if the Rajya Sabha rejects or blocks them, a joint session of Parliament should be called. The government cannot allow these changes to be filibustered like the Land Acquisition Act was in 2014.

Modi, a reluctant privatiser till two years ago, has clearly crossed a self-imposed Lakshman Rekha and bought into the idea of getting government out of many businesses. Modi in Delhi is aligning his ideology with what he seemed to exude when he was chief minister of Gujarat.

Third, the government has indirectly accepted that there is not going to be any revival of the investment cycle unless the government itself puts its shoulder to the wheel. This is why capital spending is rising 34 per cent next year to Rs 5.54 lakh crore, with another Rs 2 lakh crore being given to states and autonomous bodies.

Add the sops for affordable housing, and the planned asset monetisation of ports, airports, pipelines, power transmission lines and completed road and railway projects, and the country’s infrastructure pipelines will no longer run dry for want of funds. The thinking is that growth now depends on turning around the investment cycle, and this will have to be led by the public sector.

The earlier strategy was driven by a belief that government borrowings will crowd out private investment; now, there is the opposite belief, that government spending on infrastructure, partly funded by its own asset monetisation plans, will crowd in private investment. Way to go.

Fourth, again making a virtue of necessity, the government is using the Covid crisis to boost health spending by more than two-fold, from around Rs 94,000 crore in the budget estimate of 2020-21 to nearly Rs 224,000 crore next year. While much of this proposed increased spending is due to Covid and the mass vaccination plan, Modi has to make sure that the spending does not taper off once the pandemic blows over.

This, too, is in line with the survey’s observation that investment in public health infrastructure helps individuals save on out-of-pocket expenses, which, in turn, will help him increase discretionary spends on other kinds of consumption. Improved health outcomes increase demand elsewhere.

Fifth, the jobs crisis has not been addressed meaningfully in a direct way. It has been assumed that the revival of growth will, in itself, help restore jobs growth to pre-pandemic levels. That may happen in the short term, but the long-term structural problem of the economy’s low employment elasticity remains.

Sooner than later, the government has to focus on more direct incentives to grow employment, both by reducing the regulatory burdens on small firms and by incentivising new jobs in job-creating sectors.

Jobs remain challenge No 1 for Modi. The farmer angst cannot be solved by higher MSPs (minimum support prices) or a repeal of the reforms, but by creating jobs in cities and in rural agro-industry and services which can then absorb agriculture’s excess labour.

The production-linked incentive scheme for manufacturing – which will cost Rs 1.95 lakh crore over five years – will bring in some new jobs, but largely the growth has to be in services based in cities. The massive investments proposed to expand bus fleets (Rs 18,000 crore), metros and other urban projects suggests that growth and jobs will be urban-driven.

Maybe, that’s why farmers are protesting at the gates of Delhi. They know that their future is not in agriculture. That message needs to go out more strongly now. More jobs in cities, not more MSPs to keep the unemployed stuck in low-productive rural areas.

In 2020-21, subsidies on food, fertiliser and fuel – and related agri-subsidies – were well over Rs 6 lakh crore. Throwing more good money after bad is not going to make the problem of rural underemployment go away.

The budget raises the hope that the lessons of the last decade – low jobs growth despite headline GDP growth – are being slowly internalised.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.