Economy

Rajan Explains What's Exactly Wrong With Public Sector Banks

Vivek Kaul

Feb 17, 2016, 08:20 PM | Updated 03:42 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

For every ₹100 of loan given by public sector banks, ₹17 worth of loans are in a dodgy territory. ₹6.2 have become a bad loan, where the repayment of the loan by the borrower has stopped happening. ₹7.9 has been restructured i.e. the repayment of the loan has been placed in a moratorium for a few years.

In a speech he made last week Raghuram Rajan, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India, put forward some very interesting data points.

It is well known by now that the lending growth of public sector banks has been very slow as they grapple with burgeoning bad loans. Nevertheless, agglomerated data on the loan growth of public sector banks is generally not available in the public domain.

As Rajan said:

Non-food credit growth from public sector banks, the more stressed part of the system, grew at only 6.6% over the calendar year 2015. Industrial credit growth for PSBs was only 3.3% while growth in lending to agriculture and allied lending was only 10.4%. The only area of strength was personal loans, where growth was 16.9 %.

Banks give out loans to the Food Corporation of India to run its operations. After adjusting for these loans, what remains is the non-food credit growth. The overall non-food credit in 2015 grew by around 9.3% (actually between December 25, 2014 and December 24, 2015) against 6.6% of public sector banks. This tells us very clearly that the loan growth of public sector banks has been significantly slower than the overall non-food credit growth.

In fact, the only area where lending of public sector banks has been robust enough is what RBI refers to as personal loans. These personal loans are different from what banks refer to as personal loans. Personal loans as categorised by RBI include home loans, vehicle loans, education loans, credit card outstanding, loans given against fixed deposits, shares and bonds and what banks call personal loans.

How does the situation of public sector banks look in comparison to private sector banks? As Rajan said:

In contrast, non-food credit growth in private sector banks was 20.2 %, in agriculture 25.4%, in industry 14.6%, and 23.5% in personal loans. Put differently, in each of these areas except personal loans, loan growth in private sector banks was at least 10 percentage points higher than public sector banks, while loan growth in personal loans was 6.6 percentage points higher.

The loan growth of private sector banks at 20.2% was significantly higher than that of public sector banks at 6.8%. As Rajan put it:

The most plausible explanation I have is that the stressed balance sheet of public sector banks is occupying management attention and holding them back, and the only way for them to supply the economy’s need for credit, which is essential for higher economic growth, is to clean up. The silver lining message in the slower credit growth is that banks have not been lending indiscriminately in an attempt to reduce the size of stressed assets in an expanded overall balance sheet, and this bodes well for future slippages.

Hence, public sector banks have been going slow on lending primarily because they already have a huge amount of bad loans piled up and they don’t want to continue to lend indiscriminately and have more bad loans piling up. What Rajan is essentially saying here is that the public sector banks could have continued on their indiscriminate lending spree and expanded on their loan books. In the process, the total amount of bad loans as a proportion of the total loans given out by banks would have come down, at least for a short time.

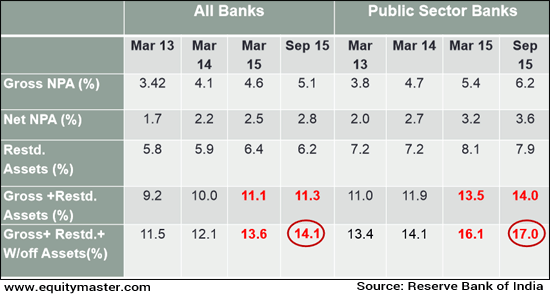

The fact that they did not do that is a good thing, feels Rajan. But the damage of their indiscriminate lending in the past is now coming out in the open. Take a look at the following table.

Extent of the problem

The bad loans plus restructured assets plus the assets written off in total made up for 17% of the books of public sector banks. This means that for every ₹100 of loan given by public sector banks, ₹17 worth of loans are in a dodgy territory. ₹6.2 have become a bad loan, where the repayment of the loan by the borrower has stopped happening. ₹7.9 has been restructured i.e. the repayment of the loan has been placed in a moratorium for a few years. In some cases, the borrower does not have to pay the interest during the moratorium period. In some other cases, the tenure of the loan has been extended. Further, ₹3 out of every ₹100 has been written off, with no hope of recovery of the loan.

Now how do private sector banks and foreign banks perform on the same parameters? Take a look at the following table.

Divergent NPA trends

What the table tells us very clearly is that the situation in private banks and foreign banks is significantly better than public sector banks. In private sector banks ₹6.7 out of every ₹100 of loans is in a dodgy territory. In case of foreign banks, the number is even lower at ₹5.8.

What this tells us very clearly is that the problem of bad loans is largely limited to public sector banks. And it is interesting that the large borrowers are primarily responsible for the mess in the banking system. This becomes clear from the following table. Public sector banks make up for close to three-fourths of the Indian banking system.

Divergent NPA trends

As can be seen from the table medium and large industries are primarily responsible for the mess in the banking sector. Rajan also said during the course of his speech that all bad loans were not because of malfeasance. As he said:

Let me emphasize that all NPAs are not because of malfeasance. Indeed, most are not. Loans can go bad even if the promoter has the best intent and banks do the fullest due diligence before sanctioning. Nevertheless, where there is evidence of malfeasance by the promoter, it is extremely important that the full force of the law is brought against him, even while banks make every effort to put the project, and the workers who depend on it, back on track.

Let’s sincerely hope that this happens, else we will have a situation where banks will have to write off more and more of their bad loans, with the taxpayer having to pick up the ultimate bill. And that can’t possibly be a good thing.

This article was first published here.

Vivek Kaul is the author of the 'Easy Money' trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek