Economy

Slowdown’s Hidden Cause May Be Modi’s New Wall Between Legit And Illegitimate Cash

R Jagannathan

Sep 20, 2017, 01:33 PM | Updated 01:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Everybody is perplexed about India’s declining growth rate. While some blame it on demonetisation and the teething troubles with goods and services tax (GST), others on external factors, and yet others on the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) obstinacy in holding interest rates high when inflation is moderate.

Surjit Bhalla, writing in The Indian Express on 19 September, put the blame almost entirely on interest rates. He wrote:

If one has to explain the growth slowdown without recourse to conspiracy theories about data manipulation… one has to begin to answer the following two questions: What determines growth, and which of these determinants was flashing a red signal before demonetisation. In most countries, the above question has the same answer – look at interest rates, stupid. No matter what country you go to, central bank and government officials have the same answer and the same policy: If you want to increase demand (up the GDP growth rate), decrease interest rates; if you want to decrease demand, increase interest rates.

There’s no doubt that the RBI has kept rates too high at a time when growth is the bigger challenge, but Bhalla probably oversimplifies when he suggests that cutting rates is the silver bullet one needs to get growth up.

Actually, there is one large, and unseen, factor no one mentions. This is simply because it is difficult to prove with numbers. And those who know about it, will not say so, since it will incriminate them.

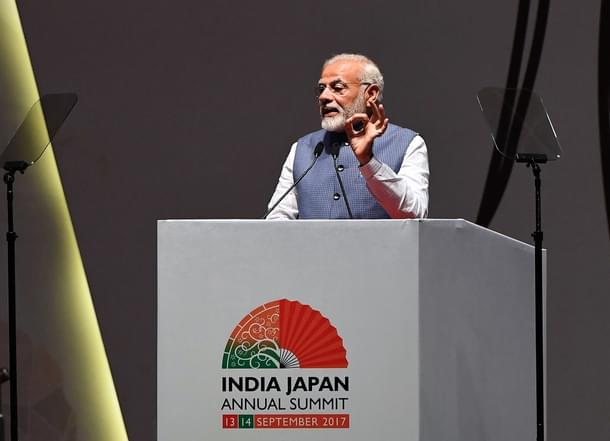

It is my hypothesis that the current slowdown – which began five years ago – is prolonged because the Narendra Modi government has substantially sealed the border between illegal (and tax-avoided) capital sources and legal ones. Before Modi’s attacks on black money – whether through voluntary disclosure schemes or demonetisation or the ending of tax loopholes for anonymous funds flowing through the Mauritius, Cyprus and Singapore routes – the borders between legit and illegitimate sources of finance were porous. Now, the illegal money, whether held in India or in tax havens abroad, is stranded, unable to come to the aid of corporations and business owners.

An illustration from 2010-11, when India was just recovering from the Lehman shock, tells us what used to happen earlier, whenever domestic companies needed additional capital. They simply brought it back clandestinely from illegal hoards abroad. They could also use the local stock markets to generate surpluses for investment through shell companies.

A Kotak Securities study suggested that nearly $40 billion of funny money may have come into India in 2010-11, though it could not prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. The report said:

Our study of exports data of major engineering companies (including automobiles and metals) shows that the increase in their exports does not reconcile with the steep increase in official exports data. In fact, the gap is quite substantial.

A report in Firstpost, written by me nearly three years ago, noted:

The official export data shows 79 per cent year-on-year export growth in 2010-11. Exports by engineering companies in the BSE 500 (the cream of India Inc) show just 11 per cent growth. If you want to know the difference in dollars, the engineering export jump accounts for $30 billion (up from $38 billion to $68 billion). The figures for the BSE 500 show a jump of just Rs 61 billion (rupees, not dollars). Converted at the rate of $1= Rs 44, this is just $1.38 billion. Where did the rest of the $28-and-odd billion come from?

The Kotak report had this probable answer:

Some reports have alleged that some individuals may have been compelled to bring back funds through the official route by simply over-invoicing exports or even resorting to fraudulent exports, thanks to (1) increased international scrutiny of unaccounted funds in bank accounts in Switzerland and other financial centres, and (2) heightened debate in India about action against unaccounted overseas wealth.

Two big examples quoted by the Kotak report related to exports of metals and metal products. This figure more than doubled from $13 billion to $ 29 billion – a rise of $16 billion. But actual results for 22 large companies in the BSE 500 showed a growth of less than $1 billion.

Then there was the example of “copper articles”, where exports zoomed four times. And this is a metal India is not known to export too much of.

We need not speculate how much of the money came in through over-invoiced exports, but rest assured, this used to happen. Much of this money could have been routed through smaller front companies, or even shell companies, which are now under attack. Before GST was implemented on 1 July, the government cancelled the registrations of one lakh shell companies. More recently, two lakh shell companies had their bank accounts frozen.

Now consider the current scenario. With banks unwilling to lend money to promoters whose loans have gone bad, the only solution is to bring in more equity. But with clandestine routes closing steadily, whether it is through Mauritius or Cyprus, or even money generated in the stock markets using participatory notes and shell companies, the elimination of incognito funds from foreign or domestic sources essentially means that those with such resources can’t easily bring them back to rescue defaulting companies.

Earlier, promoters could simply claim project costs have inflated, and pressured banks to lend more by bringing in a small equity contribution through clandestine routes. But these routes are now closed substantially.

Worse, old rent-seeking avenues like cheap spectrum or coal blocks are closed, too. Which means the promoters who won these bids now cannot obtain foreign funds on the basis of access to corruption-influenced, cheap access to resources. When resources are fully-priced, it means higher borrowing costs and lower margins.

These are some of the factors behind the slow revival in the investment cycle. Not only are corporations deleveraging, they are also forced to generate profits from existing legitimate investments, and can’t bring in illegal funds from other sources.

Demonetisation and the shift to the GST have made the business of generating more resources for investment even more difficult.

The capital crunch resulting from this new normal, where surpluses for fresh investment have to be generated largely through normal profits and market expansion, is a big reason for slow revival. And since banks are also more cautious about lending to promoters, who can’t bring in cash from legitimate sources, investment is simply not taking off.

India Inc is still to adjust to this new normal, especially since they can’t anymore count on friendly bankers and political influence to gold-plate projects and generate their own equity contributions from this capital cushion.

Legitimate wealth and illegitimate cash hoards have now been separated into two impermeable compartments. The tax-evaded money is trapped outside business, making it harder for businessmen to invest in growth.

There are only two remedies to this situation.

First, announce an amnesty scheme that no one can refuse. This means lower taxes and penalties, and guarantees of no prosecution. The two voluntary disclosure schemes were simply too tax-unfriendly for big wealth owners to take the plunge.

Second, reflate the economy through higher dollops of government spending, including a revival package focused on recapitalising banks, investing in infrastructure, and boosting demand through excise cuts.

The consequences of going relentlessly after illegitimate money is a drop in legitimate money for investment.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.