Economy

Why Modi Government May Find It Hard To Win Against Arhtiyas Of Punjab And Haryana In The Short Run

Arihant Pawariya

Mar 09, 2021, 05:13 PM | Updated 05:13 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

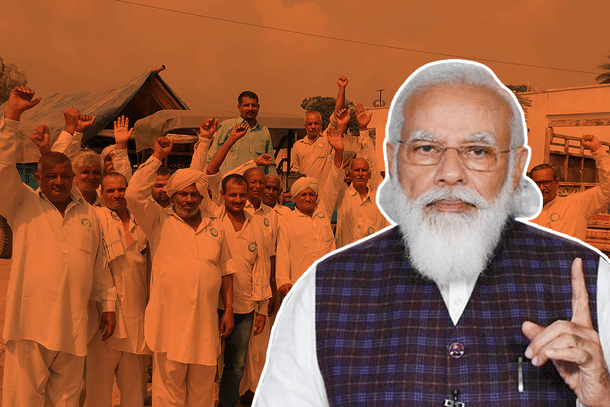

The Punjab Arhtiya Association announced on Friday (5 March) that it will be launching a strike against the Narendra Modi government for the latter’s decision to deposit minimum support price (MSP) amount directly into the bank account of farmers.

Currently, the Centre pays the MSP apart from a fixed commission fee to arhtiyas (commission agents or middlemen) who procure the produce from the farmers and sell it to private players as well as the government.

Arhtiyas then transfer the amount to farmers. This system is most entrenched in Haryana and Punjab for these states are the biggest beneficiaries of the MSP regime in paddy and wheat crops, and have a strong network of mandis.

On 4 March, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) had issued a directive to the Director of the Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs Department seeking land records of the farmers to make direct online payment to their bank accounts from the rabi marketing season 2021-22.

Arhtiyas see this as the latest attack on their interests and as a revenge for supporting farmers of Punjab and Haryana who have been protesting against the Centre’s three farm laws aimed at reforming the agriculture sector. They have threatened to stop the procurement of wheat from next month.

This row is not new. In 2019, the Punjab state government had directed all procurement agencies to link the bank accounts of farmers with the Public Finance Management System (PFMS) portal and threatened to withhold commission fee and administrative charges of arhtiyas if they don’t follow the order.

Obviously, they got angry and protested against the move for they feared that this was a precursor to cutting them out of the payment process between farmers and the government. Now, with the Centre’s latest directive, those fears have come true.

However, there is a reason why arhtiyas enjoy the influence they do in agriculture landscape of Haryana and Punjab and it’s not going to go away anytime soon, especially if the status quo continues in the MSP regime and procurement system. That’s why they are fighting tooth and nail against the three farm laws which will bring private investment, reduce reliance of farmers on MSP and potentially replace arhtiyas with other players.

“Arhtiyas are first and foremost moneylenders. They are the loan givers of first resort for us. If there is an emergency in the family, it’s the arhtiyas that farmers approach because banks either take lot of time to process the loans or don’t entertain farmers at all. Additionally, their rate of interest is lower than the prevailing rate in informal moneylending market (Rs 1.5 interest per Rs 100 loan amount as compared to Rs 2 interest from non-arhtiyas),” says Vikas Chaudhary, a rich farmer, who cultivates around 40 acres in Sonipat’s Gohana town.

The role of arhtiyas as moneylenders was something that was highlighted by every farmer we spoke to in Haryana. Even at Rs 1.5 interest per Rs 100, the rate comes to around 18 per cent per annum.

To put this in perspective, rate of interest for Kisan Credit Card (KCC) loans is effectively 4 per cent/annum if the farmers pay on time as they get 3 per cent subvention for timely payment.

“Farmers, especially the ones with small landholdings, are in need of money all the time. Most of them have already taken KCC, spent the money and can’t use the facility unless they repay the leftover amount. For any other additional expenses — agricultural or personal, they have to approach the arhtiyas,” says Mohit Kadian, a small farmer, who owns four acres in Rohtak district and cultivates paddy and wheat.

Farmers and arhtiyas both are comfortable in this relationship because the immediate monetary needs of the former are fulfilled by the latter who earn great interest which is sure to be repaid during the harvest season.

Anyone who sees moneylenders charging such high interest rate is bound to see arhtiyas as evil and farmers as victims but the latter don’t because at least they get the money when they need it even if at high interest rates. This speaks more about failure of formal institutions of credit than the success of arhtiya system.

They are merely providing a service by filling a gap in credit availability market in rural areas. The government insists they are evil middlemen while they themselves and the farmers view them as necessary and essential service providers.

”Earlier, arhtiyas used to be overwhelmingly baniyas. The relationship was of different kind then because they wouldn’t be able to ’punish’ the farmers from middle castes for non-payment of loans. However, over the years, situation has changed and now the arhtiyas belong to the same landed castes that farmers hail from, so power equations are more or less the same. In fact, the arhtiyas are more powerful because it’s the rich and powerful rural players who bid to become commission agents in mandis. Given this, farmers pay loans on time,” says Jagdeep Singh, a farmer from Jhajjar district who owns two acres.

But can the Centre cut arhtiyas to size by giving MSP payment directly to farmers, bypassing the so-called middlemen? This is what the Punjab Arhtiya Association is going to protest against.

This move is going to achieve little, say Haryana farmers who are already receiving direct payment for their produce from the government.

“I got MSP payment directly in my bank account last year. The system was put in place due to Covid-19 through an online portal launched by Haryana government. Everyone got registration number and the amount of harvest sold in the mandi and they got the money as per such details. Now, even here, arhtiyas played a major role. For instance, I sold harvest of Rs 9 lakh but arhatiya put harvest of Rs 16 lakh against my registration number. He added harvest of other farmer against my account as that farmer owed some money to the arhatiya. When I got Rs 16 lakh in my account, I kept Rs 9 lakh that was mine and transferred the rest to the arhatiya who in turn gave the payment to the other farmer after deducting the amount he owed him,” a farmer from Jind district explained how the system is easy to be gamed even if there is direct payment to farmers. He didn’t wish to the named.

Farmers also talk about the help provided by arhtiyas during Covid-19 crisis.

”Haryana government decided to follow a very stupid policy of procurement. Everyone was registered through an online portal and given a receipt with procurement date. Most farmers got multiple dates which was ridiculous. Earlier, we would harvest, take the whole produce and sell it in mandi in one go. Now, we were told to go to more than once. This would’ve added transportation, storage and labour costs and put a huge burden. Arhtiyas allowed us to dump our produce in their storage facilities in one go and then they managed everything saving us a lot of money,” says farmer Umed Singh from Jhajjar.

While the debate over arhtiyas' role and importance will continue, if the government is serious about cutting out these middlemen, it will have to give an alternative to farmers for the services they provide — the biggest of them being facilitating credit easily at lower rates.

Arihant Pawariya is Senior Editor, Swarajya.