Editor's Pick

Ramachandra Guha On C.Rajagopalachari - Part 2

Ramachandra Guha

Oct 31, 2014, 02:15 AM | Updated Feb 10, 2016, 04:53 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

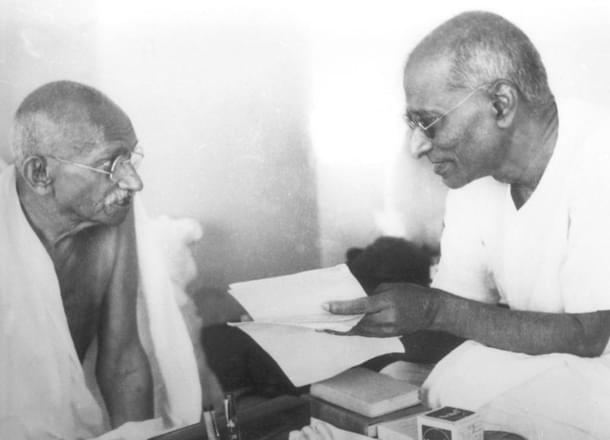

Rajaji and Gandhi

As a disciple of Gandhi, Rajaji was mostly loyal, but never subservient. He could speak to him with a clarity and directness beyond the reach of most other followers.

As a young lawyer in Salem, Rajaji stumbled upon the works of Henry David Thoreau: his book, Walden, as well as his classic essay on civil disobedience. Then he read of the Indian lawyer who was putting these ideas into practice in South Africa.

In 1913 he reprinted, at his own expense, a pamphlet describing Gandhi’s jail experiences. After Gandhi’s return to India in January 1915, he followed his activities with increasing fascination. However, he had to wait four years to meet him, their first encounter taking place in Madras in March 1919, in a house owned by the proprietor of The Hindu, Kasturiranga Iyengar.

When the two men met, Gandhi was planning his satyagraha against the Rowlatt Act. Rajaji energetically joined in, following the path of non-co-operation with the fervour of a convert. He went to jail in December 1921 and, after he came out a few months later, started an ashram of his own in Tiruchengode, to promote the Gandhian programme of khadi, prohibition, Hindu-Muslim harmony, and the abolition of untouchability (By now his law practice was a thing of the past). Then, when Gandhi announced a fresh round of satyagraha in 1930, he chose Rajaji to be the first to break the salt laws in South India.

Rajmohan Gandhi writes that, in all these campaigns, ‘the Mahatma received C. R.’s instant understanding and wholehearted loyalty’. Another knowledgeable historian, Antony Copley, has called Rajaji ‘Gandhi’s Southern Commander’. Or, as the Collector of Tanjore at the time of the Salt Satyagraha put it, he was ‘probably the ablest and certainly one of the most intransigent’ of Gandhi’s followers.

On two separate occasions Rajaji was Gandhi’s ‘front-man’ in beating off a challenge from Bengal, the province that had been in the vanguard of the freedom struggle before the Mahatma’s rise. In the Nagpur Congress of 1922 he made the decisive speech that turned the hall against Chittaranjan Das’s promotion of council-entry and in favour of Mahatma Gandhi’s more militant programme of non-violent non-cooperation.

Seventeen years later, he made another sharp speech, at the Tripuri Congress, held on the banks of the river Narmada. Rajaji’s barbs were aimed again at the Bengal party, but he spoke this time from the side of caution, rather than radicalism. For the office of President, the Gandhians had put up Pattabhi Sitaramayya to oppose the incumbent seeking re-election, Subhas Chandra Bose. Rajaji’s intervention was marked by the sarcasm for which he was notorious. I quote:

There are two boats on the river. One is an old boat but a big boat, piloted by Mahatma Gandhi. Another man has a new boat, attractively painted and beflagged. Mahatma Gandhi is a tried boatman who can safely transport you. If you get into the other boat, which I know is leaky, all will go down, and the river Narmada is indeed deep.

As a disciple of Gandhi, Rajaji was mostly loyal, but never subservient. He could speak to him with a clarity and directness beyond the reach of most other followers.

When, in 1924, the Mahatma threatened to abandon politics for social work, C. R. told him that would leave the ‘national organisation [the Congress] to vacillation and drift’; indeed, it would have ‘the worst consequences’ for the future of the freedom movement. Ten years later, the Mahatma moved to retire again, a decision that even Patel and Rajendra Prasad seem to have acquiesced in.

This time Rajaji was even more forceful in his dissent. ‘Your retirement from the Congress will be a suicidal step’, he told Gandhi: ‘An intense and irrevocable feeling of defeatism will spread over the whole nation, and kill political hope and enterprise… If you think you can retire from the Congress now and keep it and yourself both or either politically important, I think you will be sorely disappointed’.

Rajaji could tell Gandhi that he was being irresponsible, and he could also tell him that he was wrong. Never more bravely than in the summer of 1942, when he went completely against the grain of nationalist opinion in opposing the Quit India movement.

Rajaji thought a fresh satyagraha foolish when the situation demanded dialogue and reconciliation with both the British and the Muslims. As he bravely (and as it turned out correctly) put it: ‘There is no reality in the fond expectation that Britain will leave the country in simple response to a Congress slogan’.

Besides, by asking the British to leave, the Congress was issuing an open invitation to a colonizing power more brutal by far, the Japanese. Fortunately, said Rajaji, Britain ‘cannot add to her crimes the crowning offence of leaving the country in chaos to become a certain prey to foreign ambition’.

This opposition made ordinary Congressmen abuse and even—at a meeting in Bombay—throw black tar at Rajaji. The Mahatma, characteristically, would not allow political disagreement to come in the way of personal friendship. Their ties had been strengthened by the marriage, back in 1933, of Gandhi’s son Devadas to C. R.’s daughter Lakshmi.

I found a lovely little note of 1935, written from Rajaji’s ashram in Tiruchengode. ‘Lakshmi and babies are doing well in this climate. Specially Tara enjoys the open space and dustless, motor-less, grounds available for her tiny wanderings’. As the years went by, Rajaji’s manifest interest in their grandchildren allowed Gandhi to develop, almost for the first time, a love for little babies who were descended directly from him.

Rajaji could disagree with Gandhi—and disagree sharply—but on some fundamental issues he was completely with a man whom he variously addressed in letters as ‘My dearest Master’, ‘My dear Mahatmaji’, and ‘My dear Bapu’. One such issue was the abolition of untouchability, whose centrality to the Gandhian struggle Rajaji recognized earlier than any member of Gandhi’s inner circle.

A second was Hindu-Muslim harmony, a cause to which he was as devoted as the Mahatma himself. A third concerned the dignity of labour. Spinning, cleaning toilets, cleaning one’s shoes—all these came easily to him, although they were scorned by his fellow Iyengar Brahmins and by the fashionably left-wing nationalists with whom he was also obliged to consort.

When Gandhi was assassinated, on 30th January 1948, Rajaji was serving as the first Indian Governor of Bengal. He flew to Delhi to attend the cremation, and came back with a portion of the ashes.

The ceremony in the Hooghly has been described in a memoir by the Governor’s Military Secretary, Bimanesh Chatterjee. A motor launch took the party to the middle of the river, and the Governor was handed over the urn containing the ashes for immersion. As he took the urn ‘he became so overwhelmed that… he perilously swayed forward, and a couple of us had to hold him back. … When Rajaji finally sat down, he appeared exhausted. As the boat was speeding towards the bank, Rajaji said, “The ashes were pulling me”’.

Two letters to Rajaji illustrate what united him with Gandhi, and what divided them both from some other kinds of Indians. The first, written in October 1946 by a lawyer living in Sandur, chastised Rajaji for prescribing non-violence. This man sarcastically asked whether ‘because Gandhijee sings praises of non-violence in season and out of season, you too (being his relative) feel like delivering your sermon?’ The lawyer disapproved of the sermon, and seemed to think there were less and less people willing to hear it. ‘Consciousness has dawned upon the minds of the Hindus (even Congressite Hindus) that consolidation as Hindus would alone save them from political extinction. Today’s Hindu nation does not recognise “M. K.’s” and “C. R.”! It needs Savarkars and Mookerjees!”

The second letter was written to Rajaji on 12 February 1948, by a Muslim living in Sevagram:

Dear Brother,

Sitting in the busy little cottage of the Mahatma—busy with the crowds coming in to look at his vacant seat… —I am turning to you in sad contemplation.We need prophets. I am convinced that we are left without a prophet now.

India will be lost if the opportunity to serve the world with his message and teachings is lost. You are I believe the fittest one to lead India in the Mahatma way. Muslims should be made to realize that the Mahatma way is the Quranic way.

A yearning and sad soul cries to you from near the humble seat of the great man…, to lead India to fulfill the Mahatma’s message of Ahimsa, Truth, Casteless and Classless society.

Today, as in 1948, the future of India seems to hinge crucially on the relationship that the dominant community, of Hindus, is able to negotiate with members of other religious groupings. To beat them into submission; or to work lovingly and co-operatively with them. These were the alternatives once offered to Gandhi and Rajaji; and these are the alternatives now offered to us. Would we choose as wisely?

Up Next: Part III – Rajaji and Nehru

This essay first appeared in Ramachandra Guha’s book ‘The Last Liberal and Other Essays’ (2004). It is being reprinted with the permission of the author.

Ramachandra Guha is an author, historian and columnist based in Bangalore.