Heritage

Seven Thousand Wonders Of India Part III - Rajasimha Pallaveshvaram

R Gopu

Aug 09, 2020, 03:04 PM | Updated 03:04 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

“Kailasa leelaam apaharathi,” declared Rajasimha Pallava, who conceived Rajasimha Pallaveshvaram (the temple of Ishvara worshipped by Rajasimha) in Kanchipuram, the temple capital of India.

Translation: “It has captured the splendour of Kailasa”, so much so, that Vrshaanka, the God Siva, whose emblem is the bull, would leave Kailasa and settle in Kanchipuram.

After all, where better than the city extolled as “Nagareshu Kanchi” by mahakavi Bhaaravi himself?

The pun in Vrshaanka is that the bull was also the Pallava’s emblem!

Ekambareshvara, Varadaraja and Kamakshi temples attract more devotees in Kanchi. But Kailasanatha temple, as Rajasimha Pallaveshvaram is known for, has enchanted artists and connoisseurs through centuries.

It is, perhaps, the best kept secret of Tamil Nadu. Age cannot wither its beauty, nor custom stale its infinite variety.

Rajasimha Pallava

Rajasimha defies definition, but admits description.

Not a modest king, as evidenced by his 244 titles etched on the temple’s walls, Rajasimha had little to be modest about, in artistic achievement.

If the skills he proclaims in music and political and military mastery were true, then he stands out as one of the finest kings of India, and the world; a star among the illustrious Pallavas.

He called himself Atyantakaama, a man of Infinite Desires; KalaaSamudra, the Ocean of Arts; Ishvara Bhakta, devotee of Siva; Yuddhaarjuna, an Arjuna in battle; VeenaNarada, a Narada in music; KaviPrabodha, patron of poets; ItihaasaPriya, fond of history; DooraDarshi, a Visionary.

And what a visionary! What a vision!

Inscriptions

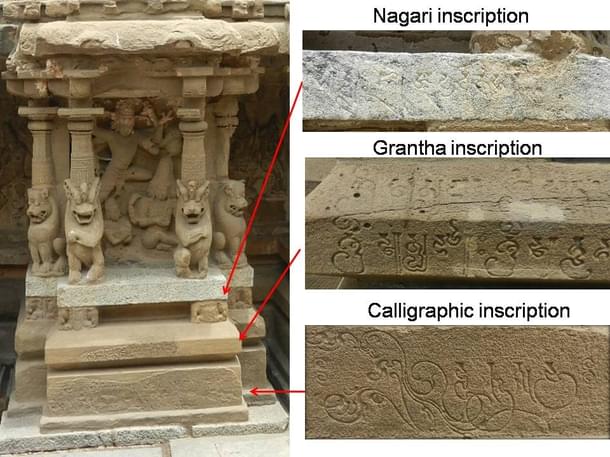

The establishment inscription of this temple, a 12-stanza Sanskrit poem in Pallava grantha script, is etched on the top layer of the adishtaana, made of granite slabs, which reinforce the structural strength of this sandstone temple.

It declares that rishi Angiras, born of Brahma’s thought, begot Brihaspati, Indra’s mantri. Brihaspati’s son, Shamyu, begot Bharadvaaja, who begot Drona, guru of the Pandavas and the Kauravas.

Of Drona was born Ashvatthaama, to whom was born Pallava, a son with kshatriya valour in every feature. Though born in a Brahmin lineage, he was the first of his dynasty.

In this line, came Ugradanda Parameshvara Pallava, whose son was Atyantakaama (Rajasimha’s favorite title).

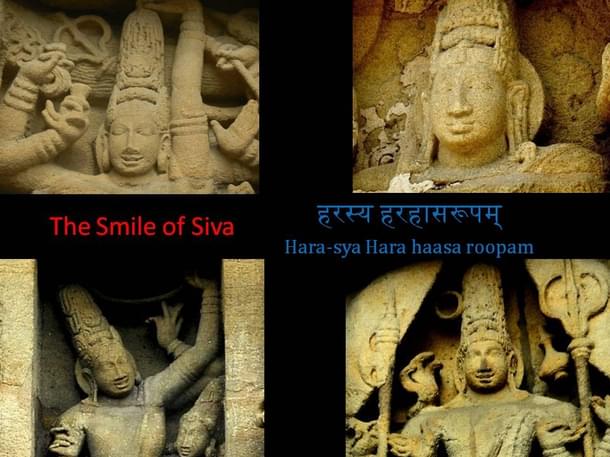

Abhram-liha (cloud licking) — a skyscraper, the temple resembles Hara’s captivating smile (“Harasya hara-haasa-roopam”), continues the poem.

Has even Kalidasa, famous for metaphors, compared architecture to a God’s smile?

Athi adbhutam!

And Siva in so many forms smiles in so many ways, to captivate heart and soul.

/

Architecture

Atimaanam. This one word captures the architecture of the sanctum. Kalaasamudra has saved us from an ocean of description, with a pithy definition.

Maanam is the Sanskrit word for measure. Vimaanam, meaning well-measured, is the Indian sthapathi’s jargon for the roof of a temple.

This Atimaanam (immaculately measured) so awed Rajaraja Chola, that he called this temple Kanchipurattu Periya Tiru-k-karrali, the Great Stone Temple of Kanchipuram.

Three centuries later, Rajaraja Chola built Rajaraja Choleesvaram, the Great Stone temple of Thanjavur; his descendant, Narasimha Chodaganga, built the Grander Sun temple of Konark — both surely inspired by Rajasimha Pallava.

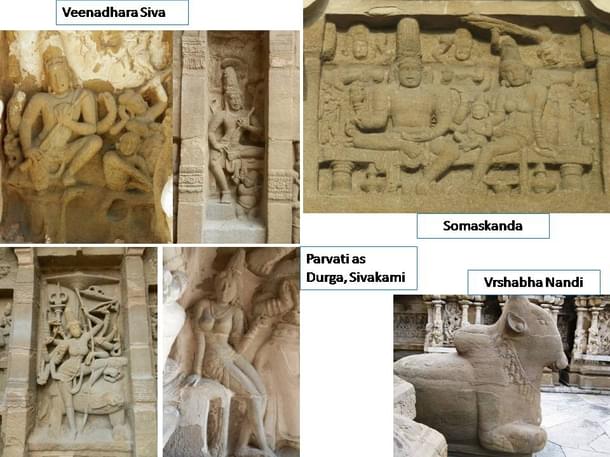

The garbhagriha has a 16-sided Dhaara Linga, and a Somaaskanda panel on the back wall.

Somaaskanda means sa-uma-skanda, Siva accompanied by Uma and Skanda, popular as the main deity in Pallava temples.

Like Kumara was born to Parameshvara, Rajasimha was born to Parameshvara Pallava, says the inscription.

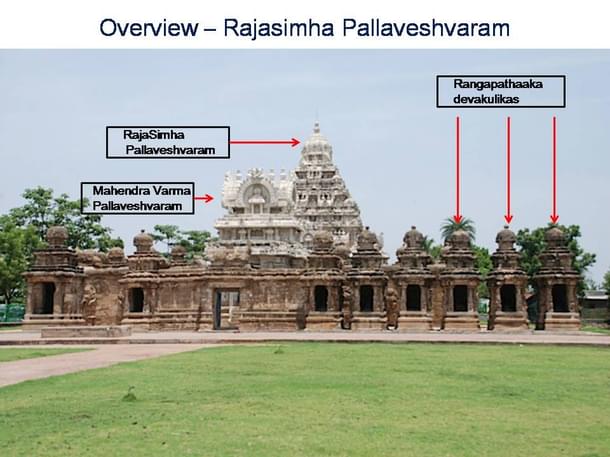

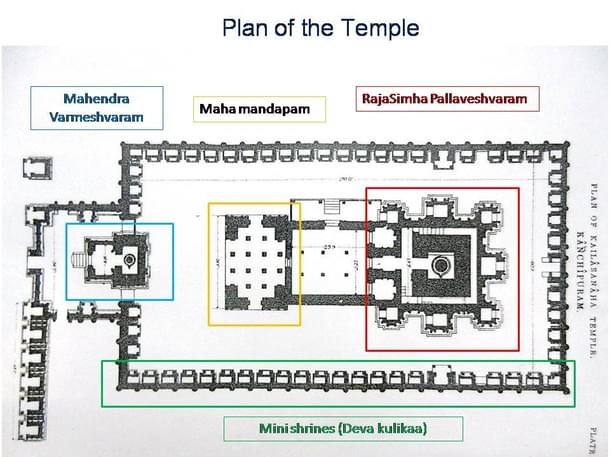

In the front courtyard is a smaller temple built by the prince Mahendra Varma III, while a row of devakulikas is built by queen Rangapataka from the whole temple complex.

Remarkably, therefore, Somaaskanda is a metaphor, for the whole layout!

Several unique or trailblazing features distinguish the temple:

· Sandhaaram: an inner circumambulatory corridor, first in a Tamil Dravida temple.

· Khanda haarmyam: Nine sub shrines, six facing east, three facing west, abutting the external walls of the sanctum.

· Devakulika-s: A garland of cell-like mini shrines, each a temple shadvarga. They feature:

o Somaskanda: Eastern and Western corridors.

o SamharaMurthy: Southern corridor.

o AnugrahaMurthy: Northern corridor.

o Parvathi: spaces between devakulikas.

o Brahma, Vishnu, Durga, Gajalakshmi: front courtyard.

· Simha stambha: Magnificent rampant lions adorn every major pilaster and pillar.

· Praakaara madil: A surrounding wall, punctuated with rampant lions or yali-s

· Sarvatobhadra: Dvarashalas adorn the four directions, but three of them hold sculptures.

· Eastern Dvarashaala: An entrance arch, the oldest in any Kanchipuram temple.

· Gomukha: an outlet drains abhisheka water from the sanctum into a stone tank.

Far in the distance sits Nandi, surrounded by pillars.

Sculptures

The uniqueness that its architecture endows, is enhanced by the grace, elegance and originality of sculptures. The sthapathi has only spared the floor, it seems, and that too reluctantly.

So festooned is every wall, every niche, even the recessed spaces that are hard to view, let alone sculpt, one wonders what fervent spirit possessed them. Was it the insatiable desire of Atyantakaama?

The largest sculptures, about 9-feet-tall are in the nine khanda-haarmyams. The east facing front four have Urdhva Tandava and Sandhya Tandava, twice each, the middle two have Sukhasana Siva, and the west facing three feature Bhikshatana, Gangadhara and Tripurantaka.

The Dakshinamurthy panel, one of five large narrative panels on the wall of the sanctum, is most striking.

Bounded by the ferocious rampant lions, it is the picture of serenity, as Siva, under a banyan tree, teaches the rishis Sanaka, Sanatana, Sanantana and Sanatkumara wordlessly. His garment is a study in artistic delicacy.

So too, the elaborate torana above him. His patta shows he is in yoga, but not the familiar pose, but a casual sukhaasana.

Lions (smiling!) and deer, relaxing together, indicate the serenity of an ashrama. The elephant represents wisdom. Every figure is unique — a Pallava hallmark.

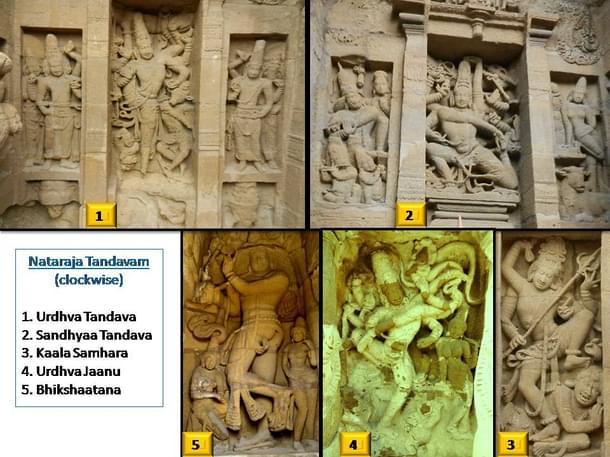

No other temple portrays the variety and elegance of Nataraja Tandava better.

He dances Urdhva Tandava, Vishnu and Brahma watch in vismaya, while Nandi and ganas try to accompany his dance.

The sandhya taandava, in a stance called Garuda-plutha, one knee on the ground, is by far my personal favourite.

Ganas play several instruments in accompaniment, Nandi enjoys and an adoring Parvati watches daintily. Besides her is an ancient musical instrument called the dhaardhuram.

Even as Kala Samhara and as Bhikshatana, Nataraja exults in rhythmic undulation. Tamil poet Thirunavukkarasar describes Bhikshatana as vattanaigal-pada-nadanthaar, walking in semi-circles.

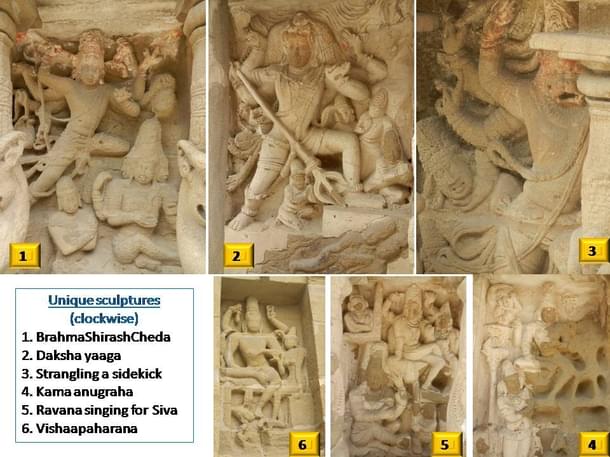

Siva as musician, veenadhara, extends this theme. In one panel, Ravana entertains Siva with a concert.

Parvati is shown in various poses, as Mahishamardhini, Durga, Bhairavi, and Sivakami.

Some episodes seen nowhere else in India, or as unique compositions, never repeated, are featured.

The episode when he furiously plucked off Brahma’s fifth head (BrahmaShirashCheda); the attack on Daksha’s yajna by Virabhadra; Siva as Vishapaharana about to drink Halahala from the churning of the Ocean of Milk — these are unique.

The Narasimha-Hiranya battle is a popular theme, but not Narasimha’s casual strangling of an asura attempting to assist Hiranya.

Several temples also feature Siva as Kama Dahana Murthy: the episode where Siva burnt Kamadeva to ashes when the latter tried to make him fall in love with Parvati.

But Rajasimha was Atyantakama — and with characteristic flourish, has Siva with Parvati as Kama Anugraha, blessing a revived Manmatha.

244 birudas of Rajasimha are etched in four scripts — Nagari, grantham, a florid grantham and calligraphic nagari, on the devakulikas surrounding the temple.

Notice that the curve over the first letter is actually shaped like the head and neck of a peacock. The curves below letters, are designed like creepers entwining around each other.

Paintings

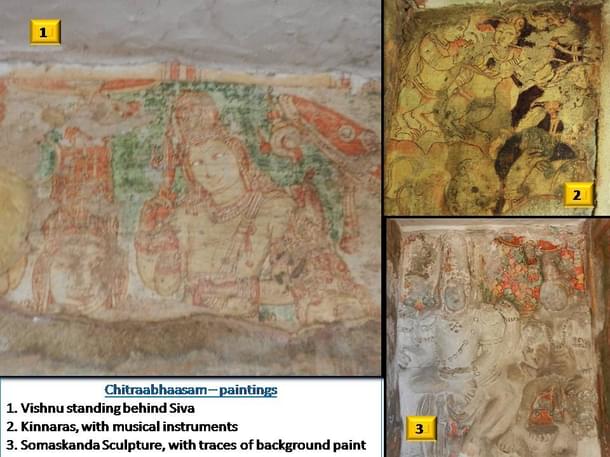

Several of the sculptures in the mini shrines exhibit traces of plaster and remnants of paint. The whole temple must have been completely plastered and painted, once.

Between the devakulikas, are two paintings of Somaaskanda, somewhat damaged. In one, Parvati is clearly visible, as the picture of compassion. In another, Vishnu standing behind Siva looks splendid.

There are also outline sketches — one, with kinnaras; another of Somaaskanda. These paintings follow the Ajanta tradition, the last few samples of such art from 14 centuries ago.

Their unfaded endurance demonstrates the excellence of the paint technology, now lost.

Later History

After Rajasimha’s death, during the reign of Nandivarma Pallavamalla, the Chalukya, Vikramaditya, invaded Kanchi, to avenge the defeat of his father Ranarasika.

Then he saw this temple. Harasya harahaasa-roopam captivated his heart, and in an act rivalling Maurya Asoka’s transformation, his heart melted by the leela of Kailasanatha, he changed his mind.

He magnanimously endowed the temple with gifts recorded in a Kannada inscription, in the pillared mandapam.

Rajasimha was KalaSamudra. Vikaramaditya was RasikaSamudra.

In his capital, Pattadakkal, his queens built two Siva temples, inspired by Kanchi Kailasanatha. We will see this next.

Other pillars bear the Tamil donation inscriptions of Viranaryana Parantaka Chola and the Vijayanagar king Kumara Kampanna.

European Contributions

In the nineteenth century, the temple was abandoned and dilapidated, and the Pallavas forgotten.

Kanchipuram shrunk as Madras grew, in the British era. A British archaeologist, Burgess, realised it was of Pallava vintage. A German, Ernst Hultzsch, recorded and translated the inscriptions.

Alexander Rea sketched and compiled a marvellous collection of its sculptures and its architecture. A Frenchman, Jouveau-Dubreuil, discovered the genealogy of the Pallavas.

C Minakshi wrote a doctoral thesis, the first by a woman in Madras University. The spirit and genius of Rajasimha inspired Nagaswamy, a Tamilian, to shine new light on this and Mamallapuram.

An American, Michael Lockwood, and his Tamil collaborators of Madras Christian College, published studies on Rajasimha’s titles and a statistical analysis of various Pallava Somaskandas.

R Gopu delivers lectures on astronomy, history, sculpture, Sanskrit, and Tamil, and is part of the Tamil Heritage Trust. He blogs here.