Heritage

While French Industrial Bodies Build Empires, Indian Associations Can't Even Play Catch Up

Adithi Gurkar

Jul 23, 2025, 01:00 PM | Updated Jul 25, 2025, 10:28 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

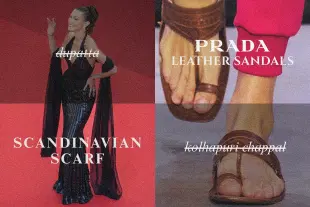

The Internet exploded when Prada unveiled their €1,200 "woven leather slippers", a barely disguised copy of India's centuries-old Kolhapuri chappals.

The backlash was so fierce that Prada executives, perhaps stung by accusations of cultural appropriation, dispatched senior officials to Maharashtra to "learn from the real cobblers" in what appeared to be corporate repentance. Yet this was not an isolated incident of Western fashion houses pilfering Indian heritage.

Around the same time, Scandinavian fashion weeks celebrated the "scarf trend", featuring flowing fabric drapes that looked suspiciously like the dupatta. The outrage was swift and justified, but it exposed a deeper, more uncomfortable truth about India's chronic inability to protect and champion its own artisanal heritage.

While we fume on social media about cultural appropriation, the real culprit is not foreign designers lacking creativity. It is India's systematic failure to build the institutional frameworks that would make such brazen copying legally and commercially impossible.

When lawyers filed cases over the Kolhapuri controversy, the Bombay High Court dismissed them, ruling that GI protection does not lie with legal professionals but with artisan associations like LIDCOM in Maharashtra and LIDKAR in Karnataka.

The devastating problem? These associations, like most of India's industry bodies, exist primarily on paper—weak, underfunded, and utterly incapable of protecting Indian heritage on the global stage.

When Paper Tigers Meet Global Powerhouses

India's GI tags are just that: mere tags. While Section 22(1)(b) of the Geographical Indications Act, 1999 makes unauthorised GI use criminal within India's borders, it is a paper tiger that only roars domestically.

This "jurisdictional firewall" renders Indian GI law powerless against transnational theft. A limitation which was starkly illustrated in the Prada controversy, where Italian courts do not recognise Indian GI registrations unless separately established under European IP regimes.

The core problem is that, unlike patents (protected internationally via the PCT) or trademarks (covered by the Madrid Protocol), GIs lack automatic global recognition.

Every new jurisdiction requires a separate registration, demanding resources out of reach for many artisan or community-based GI holders. Consequently, for the majority of India’s 600+ registered GIs, the certificate acts as a symbolic marker rather than a functional international shield.

Yet, the root of the problem lies not just in the international system’s complexity but also in India’s stubbornly reactionary approach to GI enforcement.

Rather than building robust, forward-looking institutional mechanisms, India tends to act only after a violation has occurred, by which time the damage is already done. This stands in stark contrast to the hawk-like protection afforded to GI products by European and American governments and industry bodies.

Consider, for instance, France's institutional machinery in action. French couture is not just legally defined, it is legally defended with ferocity. The term "haute couture" enjoys protection by the Paris Chamber of Commerce, while the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode (FHCM) serves as the governing body with dual missions—providing services to members and representing them before public authorities in France and Europe.

This is not a recent innovation. As early as 1921, the French press established L'Association de Protection des Industries Artistiques Saisonnieres (PAIS) to shield couture designs from imitation.

A meticulous system was developed to enforce collective copyright: every design was photographed from multiple angles to create an official design catalogue, serving as legal proof of originality. Fashion houses had to meet strict eligibility criteria, including employing a minimum number of skilled artisans, producing bespoke garments, and operating ateliers within Paris, to qualify for protection.

This built a culture of institutional vigilance, ensuring that enforcement began at the design table, not the courtroom.

Layered atop this historical legacy is France’s sophisticated international legal framework. EU-wide protection under European trademark and design laws covers all of France, while international enforcement is enabled by national laws such as Law 1991-7, implementing the EU First Trademarks Directive, and Law 2007-1544, enacting the EU IP Rights Directive.

The results speak for themselves. Armed with this institutional architecture, French fashion houses (backed by FHCM) have made significant strides in international IP enforcement. In a landmark ruling, the Court of Justice of the European Union upheld the right of luxury fashion brands to restrict authorised distributors from selling products on third-party platforms like Amazon, helping preserve the “aura of luxury” associated with French couture.

In contrast, India's fashion protection relies on a Byzantine maze of weak, fragmented bodies with zero coordination. It limps along with scattered organisations operating in complete isolation.

For instance, the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI) has no authority in international IP matters. The Apparel Export Promotion Council (AEPC) prioritises exports but lacks any enforcement mandate. Similarly, bodies like the Clothing Manufacturers Association of India (CMAI) focus on manufacturing, offering limited protection for intellectual property.

Others—such as the Synthetic & Rayon Textiles Export Promotion Council (SRTEPC), Indian Handicrafts & Gifts Fair Organisation (IHGFO), Handloom Export Promotion Council (HEPC), Powerloom Development & Export Promotion Council (PDEXCIL), and the government’s own Textiles Committee—operate in silos, with no clear overlap or legal authority to defend India’s fashion identities domestically, let alone abroad.

How Distilled Heritage Became Liquid Gold

This lack of coordination is thrown into sharp relief when compared to how other nations have successfully institutionalised cultural protection and branding, especially in sectors as niche as regional beverages.

Nations like France have built global industries on the back of meticulous legal and institutional frameworks. Take Champagne, for instance. Protected under the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system, only sparkling wines produced in the Champagne region using the traditional méthode champenoise may use the name.

Everything—grape selection, fermentation, maturation—is strictly regulated, turning what was once a regional product into a globally revered geographic indicator.

That success is underpinned by the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (CIVC), a legally empowered body comprising growers, producers, and merchants. Far from being symbolic, the CIVC actively polices misuse worldwide. It played a central role in the U.S. halting new “Champagne” labels in 2006 and securing China’s formal GI recognition in 2013.

Champagne's success transcends legal protection. By associating itself with prestige, exclusivity, and high social status through strategic luxury branding, houses like Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon, and Krug command extraordinary prices while ensuring benefits flow back to local producers through sophisticated licensing and royalty systems.

Similarly, Scotch whisky enjoys protection through the Scotch Whisky Regulations, 2009 and recognition under TRIPS and EU GI frameworks. Only whisky distilled and matured in Scotland for at least three years can be labelled "Scotch Whisky". The Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) does not just maintain standards, it aggressively pursues legal action against brands misusing the name.

The SWA's enforcement record proves formidable. In India, they fought successful cases in 1998 and 2012 against companies producing whisky labelled "Scotch", while a 2008 landmark ruling forced a Chinese distillery to stop selling fake Scotch whisky.

The SWA works with governments to negotiate favourable trade agreements, including EU Free Trade Agreements ensuring GI recognition in member states, and China Trade Agreements (2019) providing additional legal protection against counterfeits.

Across the Atlantic, while Scotland relied on legal enforcement, Mexico emphasised diplomatic leverage. After securing Denomination of Origin (DO) protection for Tequila and Mezcal, ensuring only spirits produced in designated regions using specific agave varieties can use these names, the Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT) and Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM) oversaw compliance, quality control, and branding with remarkable success.

The country then leveraged diplomatic muscle through NAFTA/USMCA Agreements ensuring only Mexican Tequila and Mezcal can be sold under these names in North America, EU-Mexico Trade Agreement protecting Mexican GI spirits in Europe, and China Agreement (2013) allowing 100% agave Tequila exports to China. They did not just protect drinks, they safeguarded entire cultural export industries worth billions.

This success is not the monopoly of centuries-old frameworks like Champagne or Cognac. Modern nations have replicated these victories with remarkable speed and sophistication.

Peru and Chile's transformation of Pisco from a humble regional brandy into a globally recognised premium spirit offers perhaps the most relevant template for India.

Both countries engaged in fierce legal battles over the name, understanding that controlling the brand meant controlling billions in export revenue. Today, premium Pisco commands shelf space alongside Cognac and single-malt whiskies worldwide.

Japan achieved similar success protecting sake's authenticity through strict production standards and international recognition, while simultaneously elevating matcha from a regional tea ceremony ingredient to a global luxury commodity commanding premium prices worldwide.

Even more impressive is Korea's success with Soju. Through coordinated state and industry backing, including savvy export strategies and cultural diplomacy, Korea turned what was essentially their version of arrack into the world's best-selling spirit by volume. Soju now outsells vodka globally.

Perhaps the most dramatic example yet comes from China's baijiu revolution. India risks once again ceding first-place status in Asia to China when it comes to spirits. What began as a humble local brew—baijiu, a sorghum-based spirit—has rapidly evolved into a global powerhouse.

Today, Chinese baijiu brands account for more than half of the total brand valuation among spirits worldwide, reflecting a remarkable transformation driven by coordinated industry, government, and branding efforts.

Three baijiu brands, Moutai, Wuliangye, and Yanghe, currently dominate the top three spots in the ‘Top 50 Spirits in the World’ rankings. Moutai alone boasts a staggering brand valuation of $21.2 billion, nearly five times that of Johnnie Walker, which ranks fifth at $4.3 billion as the top Western spirit. In a striking example of national pride and branding power, two Chinese airports, Yibin Wuliangye and Zunyi Maotai, are even named after baijiu brands.

Meanwhile, efforts to globalise baijiu continue to intensify. Expat experts are promoting brands like Ming River by partnering with U.S. restaurants eager to pair the spirit with Chinese cuisine.

At the same time, Chinese distilleries are adapting to international palates by experimenting with higher alcohol content, raising it to 40 percent, on par with vodka and whisky, and encouraging bartenders around the world to create inventive cocktails infused with baijiu’s distinctive character.

Against this backdrop of international success, India's traditional spirits languish despite possessing equal historical significance and cultural depth.

Feni, Mahua, Himachali Chulli, Nashik Wine, and Mizo Zawlaidi all suffer from identical systemic problems: weak or absent producer bodies, lack of unified marketing, inconsistent quality standards, and virtually no international treaty backing.

Among them, Goan Feni offers a revealing case study, one that carries both promise and pitfalls. The Goa Cashew Feni and Coconut Feni Distillers and Bottlers Association (GCFDBA) successfully secured GI registration for cashew Feni, a crucial first step. Homegrown brands such as Gonechi, Cazulo, Aani Ek, Moji, Sattari, and Tinto are now attempting to reposition Feni as a premium offering.

Even this success story pales beside international standards. While France's CIVC operates with legal authority backed by national law and EU regulations, GCFDBA operates as a voluntary association without statutory powers.

CIVC rigorously enforces Champagne’s méthode champenoise across approved grape varieties in limited production zones. In contrast, GCFDBA lacks robust quality grading or standardised definitions of “authentic” Feni across distillers.

Champagne enjoys legal protection in over 120 countries through decades of coordinated marketing and diplomatic lobbying. GCFDBA, on the other hand, focuses primarily on domestic recognition, with limited international presence.

CIVC actively prosecutes global misuse through legal battles and diplomatic channels. Meanwhile, GCFDBA faces challenges extending protection beyond India, with no formal mechanisms preventing international counterfeits.

A similar but underutilised opportunity lies in Nashik Wines. As India’s premier wine-producing region, Nashik has already gained attention for its fertile vineyards, favourable climate, and growing list of reputable wineries. Brands like Sula, York, Grover Zampa, and Soma have introduced quality Indian wines to domestic and international markets.

However, much like Feni, Nashik Wines struggle with the absence of cohesive institutional support. There is no central regulatory authority empowered to set industry standards, secure international GI protections, or coordinate branding and marketing at the national or global level.

While the Indian Grape Processing Board was established in 2009 with the intention of introducing comprehensive regulations for winemaking, quality control, branding, and promotion, these efforts were short-lived. The board was suspended in 2016 by the Union government following allegations of corruption and severe mismanagement of funds, bringing its mission to an abrupt halt in less than a decade.

Contrast this with how Italy operates. Through its strict classification system—including DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) and DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita)—Italy enforces rigorous production standards and regional authenticity, giving its wines global credibility.

In both cases, Goan Feni and Nashik Wines, the lesson is the same: individual ambition is not enough without institutional vision. The success of global heritage products has always hinged on a three-fold approach: strong legal frameworks, effective producer associations, and coordinated international branding. India has the heritage and entrepreneurs; now it needs the systems to match.

The same institutional weaknesses plague other Indian spirits as well. Mahua, with its incredible biodiversity story connecting tribal communities to forest conservation, lacks any unified producer body.

Himachali Chulli, with its high-altitude terroir and apricot heritage, suffers from fragmented production without quality standards.

Mizo Zawlaidi, launched in 2010 after Mizoram amended prohibition laws, is sold as a locally manufactured grape wine priced at Rs 150 under the brand name meaning “love aid.” It faces additional challenges from changing state prohibition policies.

While Mexico’s CRT and CRM evangelise Mexican drinking culture globally, turning peasant spirits into premium shelf staples, India's traditional spirits remain trapped in local markets despite representing thousands of years of indigenous knowledge.

Five Centuries of Heritage vs. Institutional Negligence

The institutional gap becomes most devastating when comparing cheese protection, a sector where Europe's centuries-old systems dwarf India's virtually non-existent frameworks.

Consider the multi-layered protection European cheeses enjoy. Roquefort (France) operates under many institutional shields. Protected by the French AOC system since 1927, it is governed by the Confédération Générale de Roquefort, which enforces strict cave-ageing requirements in natural Combalou caves.

The EU's PDO framework adds another layer through EU Regulation No 1151/2012, ensuring international protection. Roquefort commands premium prices globally, with producers regularly winning international legal battles against imitators.

Italy's approach proves equally systematic. Parmigiano-Reggiano operates under the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano-Reggiano, established in 1934. This body maintains rigid production standards across five specific Italian provinces, conducts quality inspections, and aggressively pursues trademark violations worldwide.

Known as the king of cheeses, systematic institutional protection has made “Parmesan” one of the world's most copied and legally defended cheese names.

Swiss precision takes this model even further. Gruyère benefits from the Interprofession du Gruyère, founded in 1948, which maintains AOC certification, conducts regular quality audits, and coordinates international marketing.

Swiss institutional efficiency means Gruyère’s geographic boundaries, production methods, and seasonal variations are precisely codified and legally enforceable across multiple international treaties.

Contrast this with the situation with Indian GI-tagged cheeses. India's cheese heritage reveals institutional negligence on a heartbreaking scale. Bandel Cheese (West Bengal) represents 500 years of Portuguese colonial legacy, yet today only Palash Ghosh and his family continue authentic production.

The sole institutional advocate is Saurav Gupta, owner of The Whole Hog Deli, who single-handedly pursues GI tag efforts—one private entrepreneur shouldering the survival of an entire cultural tradition.

Jammu and Kashmir’s story proves equally tragic despite recent progress. Kalari Cheese, invented by nomadic Gujjar tribes centuries ago for milk preservation during seasonal migrations, finally received GI tag status in 2023.

However, this legal recognition remains hollow without supporting infrastructure. Scattered tribal producers continue working in isolation, lacking collective representation, quality certification, or coordinated marketing beyond local markets. With India facing 195 different national IP regimes, each with unique requirements, procedures, and enforcement standards, the task of international protection becomes insurmountable for these isolated producers.

Most devastating is Sikkim’s complete institutional abandonment. Chhurpi, crafted from unique yak milk with extraordinary artisanal potential, has not even achieved GI application status. This premium heritage product remains trapped in traditional barter systems, occasionally surfacing in travel blogs but invisible to global markets.

The pattern reveals systematic institutional failure. No producer associations exist for any of these cheeses. Quality standards depend entirely on individual family knowledge. International recognition remains zero. Marketing efforts are either non-existent or limited to single entrepreneurs.

The contrast is devastating. While European cheeses benefit from century-old institutional ecosystems transforming regional products into global luxury brands, India’s equally ancient cheese traditions survive through individual heroism against systematic institutional neglect. Finding Camembert and Pecorino in Indian metros proves easier than locating these native cheeses—a perfect encapsulation of institutional failure.

Emerging brands like Nari & Kāge, Käse, and Amiksa attempt to bridge this gap through private initiative, but they are essentially building European-style institutional frameworks from scratch, competing against centuries-old systems with virtually no state or collective industry support.

The solution transcends better laws or government schemes. India needs industry associations with actual authority. Organisations that can enforce standards, coordinate marketing, pursue international legal protection, and transform traditional products into modern luxury brands without losing their authentic character.

The next time Prada copies designs, the question should be why institutional frameworks making such copying legally impossible and commercially pointless do not exist. The answer to cultural appropriation is not anger. It is building systems that make heritage products so successful and well-protected that copying becomes futile.

The goal transcends mere protection. It is institutional revolution. When Kolhapuri chappals achieve the same protected status and premium positioning as Champagne, Roquefort, and Scotch whisky, we will know this transformation has succeeded. Indian heritage will command respect not through moral appeals, but through legal consequence and market power.

Note: Kalari Cheese from Jammu and Kashmir is often commonly advertised as Kashmiri Cheese. This piece too associated Kalari Cheese with Kashmiri markets. That however does not imply a comment on the historical origins of the cheese.

Adithi Gurkar is a staff writer at Swarajya. She is a lawyer with an interest in the intersection of law, politics, and public policy.