Ideas

Beyond 'Tolerance' Lies The Realm Of Anekantavada And Quantum

Anmol N Jain

Apr 10, 2025, 10:10 AM | Updated Jun 05, 2025, 03:36 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Our world, addicted to false clarity and certainty, needs Anekantavada, which offers not just a declaration of the ultimate truth but a quiet correction. A correction that is long overdue. Because for all the talk about plurality, freedom of speech, and civil discourse, what we get in practice is ‘tolerance’.

The Poverty of Tolerance

Modern liberalism extols ‘tolerance’ as a cardinal virtue.

But beneath its moral shine lies a dull, mechanical, smug instinct—one that handles disagreement like a diplomat at a bad dinner party: smiling through clenched teeth, waiting for it to end. You can feel the grimace behind the smile.

To state it crudely: “I don’t agree with you, but I won’t punch you in the face.”

And somehow, that is supposed to be the gold standard of civilised behaviour.

In public discourse, we’re taught to ‘tolerate’ each other. “You stay over there. I won’t interfere.” It sounds noble. But in saying that, it asks for distance, not understanding.

It tolerates the other like one tolerates noise in the neighbourhood. It doesn't engage. It doesn't listen. It merely avoids.

Worse, it often carries an air of superiority: “You're wrong, but I am kind enough to let you persist in your delusion.” That is not virtue. That is arrogance wearing good manners.

That’s where Anekantavada, rooted in Jaina darshana, offers something radically different. It does not ask us to ‘tolerate’ the other. It exhorts us to understand that no single perspective, no matter how compelling, can exhaust the truth. Not even its own.

The reason tolerance is a strained virtue is because it emerges from an Abrahamic framework where truth is singular, exclusive, and final. Historically, the modern idea of tolerance took shape in post-Reformation Europe, not as a celebration of pluralism but as a grudging truce between rival ‘Truths’.

To “tolerate” was to allow error to exist without eradicating it.

Anekantavada, by contrast, arises from a Dharmic worldview, where truth is inherently diverse, contextual, and evolving. It doesn’t merely permit other perspectives, it presumes them.

Tolerance begins with monopoly and ends in resentment. Anekantavada begins from multiplicity and ends in mutual refinement.

But what if our problem isn't that we disagree too much but that we strive to understand too little?

Anekantavada: Fighting Lazy Certainty of Tolerance

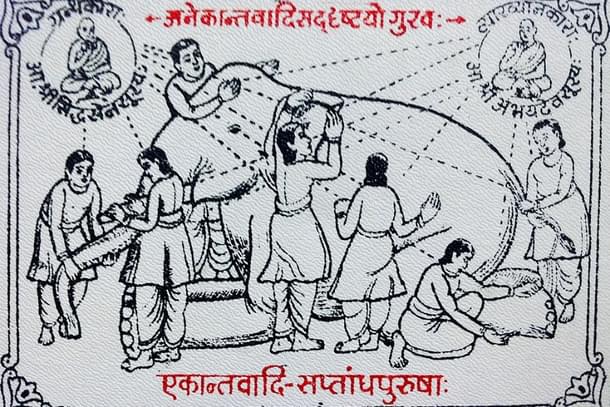

Translated literally, Anekantavada means “many-sidedness” or “non-one-sidedness”.

But unlike tolerance, Anekantavada doesn’t merely hold space for other perspectives, it seeks them. It says: “Your view may hold something that mine lacks.”

It is not a passive virtue. It’s not about peace through silence; it’s about peace through dialogue. It says that truth is not a sword to be wielded in a crusade, but a gem with many faces.

Now, this doesn’t make Anekantavada soft or indecisive, as several critics have claimed. Anekantavada is often misunderstood as “all opinions are valid.” That is false. It simply says that all opinions are partial and therefore need refinement, not rejection. It aims at precision with context.

In fact, this demands more discipline than dogma or tolerance. It asks us to live with nuance and humility. And in today’s fractured public space, that is rebellion.

Anekantavada refuses the laziness of tolerance. The latter limits our engagement. It doesn’t ask why the other believes what they do. It doesn’t seek coherence. It doesn’t challenge itself. It only avoids conflict.

Anekantavada & Quantum Physics: A Dialogue Across Time

Strangely, and wonderfully, Anekantavada is not alone in fighting the laziness of dogmatic certainty. Modern physics, too, has found itself arriving at a similar junction, a place where certainty collapses and reality becomes relational. The realm of quantum physics.

This isn’t about shoehorning Indian philosophy into science, or retrofitting logic using rhetorical twists. This is an ontological claim.

It’s about noticing how two traditions (yes, quantum physics is both science and tradition) separated by millennia, arrive at a similar humility: one through dialogue, the other through subatomic chaos.

At first glance, quantum theory might seem like a different beast with all the numbers, labs, equations. But it makes confessions similar to Anekantavada:

The uncertainty principle tells us: You can't know everything at once.

Duality tells us: Something can be two things at once, depending on how you look.

Superposition says: Reality doesn’t collapse into one version until it’s observed.

And entanglement says: Even things far apart may be deeply connected.

Here’s where things get intriguing. All of these principles can pass off as mysticism. But we know it is physics. Physics that eerily mirrors the humility of Anekantavada. These are the things Anekantavada has said for centuries.

That ‘reality is multi-sided’ not only makes for a more scientific worldview, it also makes for a more humane one.

Uncertainty Principle: Limits of Knowledge

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle states one cannot know a particle’s position and momentum at the same time with perfect accuracy. The more precisely you know one, the less precisely you know the other.

Anekantavada says the same in that absolute knowledge cannot be observed at once through a single lens. The harder you try to pin down the Truth, the more it slips away. Better to hold it with open hands.

Quantization: Reality Comes in Pieces

In quantum physics, energy isn’t continuous. It arrives in quanta, discrete packets. The smooth flow we assume is actually built from tiny, indivisible fragments.

Anekantavada, too, sees truth or knowledge as fragmented, partial, contextual, and never complete. No observer holds the whole truth. Every statement about reality is like a quantum—it reveals a part, not the total.

Tolerance lacks this awareness. It is based on the presumption of holding a whole, stable, objective truth while merely tolerating the emptiness of the other.

Duality and the Discipline of Perspective

When quantum physicists say light behaves both as a wave and a particle depending on how you observe it, they are not being poetic. They are being accurate. They are acknowledging that reality is not unitary.

Observing a system changes the system.

Anekantavada says the same of truth. Your vantage point determines what you see. And what you see, no matter how sincere, is incomplete.

In both Anekantavada and quantum physics, truth is relational. Not relative in the postmodern sense of “anything goes,” but layered and contextual. What is true depends on where you stand, what you're looking for, and how you choose to observe.

This is not license for chaos. It’s an argument for discipline—discipline in judgment, caution in speech, and openness in thought. Because what one is saying might be valid but it’s never the full story.

Superposition and Syadvada

Anekantavada is not an isolated thought. It is part of a trio in Jain epistemology, alongside Syadvada and Nayavada.

Consider the quantum concept of superposition, where a system holds multiple possibilities until observed. Schrödinger's cat may be both alive and dead while unobserved.

We find a striking parallel in Syadvada, which insists that multiple truth claims can coexist, each valid in its own scope. This is not evasion—it is intellectual honesty. To hold a view, knowing it is not the whole.

A statement, Syadvada says, must be framed with a “syad”, meaning “from a certain perspective.” So a thing is in one context, is not in another, and is both describable and indescribable in yet another.

Anekantavada, through Syadvada, trains the mind to live in superpositions. It doesn't rush to collapse reality into one state. It holds competing possibilities with care.

Entanglement and Ethics

In quantum physics, there is the concept of entanglement, the uncanny phenomenon where two particles, once connected, remain correlated even when light-years apart. One is affected when the other is touched.

Anekantavada offers not just ontological parallel but an ethical one with its own entanglement between thought and action, speaker and listener.

It teaches that no thought is isolated. To hold a view is an act. No speech is free of consequence. Every assertion affects the psyche of the other. Thus, restraint in thought and speech is not self-censorship. It is intellectual non-violence.

This is what tolerance lacks. Tolerance says nothing of the ethics of knowledge. Anekantavada integrates Dharma into epistemology.

If your certainty degrades the other, as in the realm of tolerance, maybe your certainty needs checking. What you know and what you claim to know is not just a statement. It is a karmic act.

Final Words: From Certainty to Curiosity

This is not just philosophy or physics. This is praxis. It is needed in every newsroom, classroom, and parliament. You’re either with us or against us. Right or wrong. Hero or villain. Gandhi or Savarkar.

This addiction is not just ideological but also psychological.

In public life today, Anekantavada is needed more than ever. Because our debates are no longer about truth. They are about victory. And so we tolerate each other’s presence while fantasising about each other’s erasure.

Anekantavada offers a harder path. It asks: What is the sliver of truth in the other person’s position that I might be blind to? And can I engage with it? Not to win, but to refine my own view?

This is not compromise. It is elevation.

Modern liberalism says: Let all views exist, but only mine deserves power.

Anekantavada says: Let all views refine one another because power without refinement leads to arrogance, and arrogance to collapse.

Tolerance breeds parallel monologues. Anekantavada invites a dialogue that changes both sides.

Anekantavada is not saying that truth doesn’t exist. It is saying that truth is more textured than the slogans on our timelines. More demanding than our debates allow. And more elusive than our egos will admit.

Quantum physics tells us that matter is not solid, that cause is not always clear, and that observation alters the outcome.

Jain philosophy tells us that truth is not straight, that perception shapes reality, and that because thought is action, it must be paired with kindness.

We’re not being asked to abandon logic or embrace relativism. We’re being invited to slow down our certainties.

To replace: ‘You’re wrong’ with ‘What truth are you seeing that I’m not?’

To replace ‘let’s agree to disagree’ with ‘let’s stay in the tension a little longer’.

In a world increasingly addicted to binary thinking of this or that and with us or against us, quantum physics and Anekantavada offer a subtler path.

To respect difference, not because we’re forced to, but because truth may actually reside in that gray. To engage not with the arrogance of tolerance, but with the humility of curiosity.

And perhaps that’s where peace begins. Not in tolerating each other in a condescending ceasefire, but in engaging each other. Because only when we let go of the illusion of complete knowledge, can we finally begin to learn.

Anmol N Jain is a writer and lawyer with a background in International Relations, Political Science, and Economics. He posts on X at @teanmol.