Ideas

Plugging The Gaps In Swachh Cities Through Effective Landfill Management

Anand Trivedi and Sumitra K

Jun 27, 2019, 02:36 PM | Updated 02:36 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

With less than six months to go for the 150th birth anniversary of the man whose life was a personification of cleanliness, and the promise by the current government of Swachh Bharat in urban areas closing in on its milestone of open-defecation-free and garbage-free cities, there is a need to look back at what has been achieved and what should be the way forward.

With the Swachh Bharat scheme achieving much greater public participation in its sanitation initiatives as compared to its predecessors — as exemplified by rising participation in Swachhta Sarvekshan — and its coverage increasing from 73 cities in 2016 to all cities as indicated in a recent survey (2019), the scheme has made huge inroads in addressing the urban sanitation and solid-waste management issues. About 4,165 cities out of 7,935 towns/cities are now open-defecation free and about 57 lakh household toilets and 4.8 lakh community/public toilets have been constructed with about 76,000 wards achieving 100 per cent door-to-door waste collection under the mission.

One of the key focus areas of the mission has been to achieve garbage-free cities and therefore there was a significant push towards waste segregation at source and door-to-door collection of waste. Door-to-door waste collection improves collection efficiency and controls the spread of neighborhood garbage dumps while segregating waste at source ensures that dry and wet waste are collected separately making further processing much faster and easier. Such improved processing not only makes economical sense given the business value in it, it also potentially helps improve public health and quality of life.

WHO indicates that about 22 types of diseases can be prevented/controlled by improving the municipal solid-waste management system. When the Swachh Bharat Mission was initiated, as per a report by the Central Pollution Control Board in 2013, it was estimated that only 68 per cent of the municipal solid waste (MSW) generated was collected, of which only about 28 per cent was treated by the municipal authorities, i.e., an aggregate waste treated to total waste generated ratio of about 19 per cent.

While recent data on collection and treatment efficiency is not available, interactions with urban Local Bodies clearly indicate significant improvement in collection efficiencies while a lot needs to be done to improve treatment efficiencies.

It is critical to note that while 100 per cent door-to-door collection and segregation at source will ensure that all the new municipal solid waste being generated is easier to process and makes economical sense too, the existing huge dumps of solid waste at landfill sites seen across almost every major town or city are still unaddressed under the Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) component.

A report of the Task Force on Waste to Energy by the Planning Commission, 2014, under the chairmanship of Dr. K. Kasturirangan, estimated that of about 62 million tonnes of MSW generated in urban areas, more than 80 per cent is disposed of indiscriminately at dump yards in an unhygienic manner. At this rate of MSW generation and considering 80 per cent disposal in landfills, we would need an additional 1,240 hectares to be provisioned every year for landfills. The task force had recommended that it is imperative to reduce wastes going to landfills by 75 per cent, failing which 66 thousand hectares of our precious urban area would have to be blocked, which we as a country can hardly afford.

Landfills, for the unscientific manner in which they handle dumped waste, lead to soil pollution, ground water contamination, and air pollution too due to the emission of greenhouse gases, which are extremely hazardous. As per the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), about 30 per cent of the methane emitted to the atmosphere is from landfills and methane, as we know, is one of the major ingredients of the greenhouse gases responsible for global warming. As per an estimation by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), about 600 gigagram of methane is emitted from India’s landfill sites.

For those of us who drive past the Ghazipur landfill site in East Delhi daily or have been witness to the growing size of the mountain of trash at Pirana, Ahmedabad — which has received more than 4.6 million tonnes of waste till date — it is a crucial aspect waiting to be addressed under the Swachh Bharat Mission.

Ghazipur, in fact, happens to be one of the most notorious sites commissioned for a landfill in 1984, with the dump now reaching a height of 65 meters — 8 meters short of Qutub Minar’s height! Last year, a part of this landfill caved in killing two people.

Hundreds of such saturated and hazardous landfill sites — about to become disastrous — await the attention of the policy makers. These landfills also occupy premium real estate, the value of which lies locked. So, at this rate, as per a joint report by ASSOCHAM (Associated Chambers of Commerce of India) and the accounting firm, PwC (PricewaterhouseCooper), it would require an estimated 88 sq. km of precious land to be brought under waste disposal through landfills by 2050, which is equivalent to the size of the area under administration of the New Delhi Municipal Council.

And so, the Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 should have an integral component focused on addressing landfill management. At an estimated cost of Rs 8000 per tonne of waste to be treated, this problem, with about 40 crore tonnes of waste lying to be treated across all landfills in India, will require a total investment of about Rs 3.2 lakh crore. Clearly such an amount cannot be addressed simply through public investments and would require private participation as well. But the ability of the private sector to come up with viable business models around this issue will depend significantly on the implementation of waste segregation at source and other policies/incentives offered by the government in parallel.

In the last decade or so, the number of private sector companies invested in composting and Waste-to-Energy (W-to-E) plants were closed down largely due to public outcry, problems of marketing of the compost, poor quality of feed stock, improper choice of technology and due to the non-availability of the right quantity and quality of wastes as was promised or envisaged.

Also, the heavy investments required now in treating the waste accumulated till date in the landfills, which is non-segregated waste, is much higher and probably has much lower calorific value as compared to what will be obtained from segregated waste generated in the future.

Use of landfills internationally is very different. It is only the inert residues that are stored in the landfills. So, for example in Japan, only 2 per cent of the total waste produced across the country goes to the landfills due to unavailability of sufficient land whereas about 74 per cent of the waste produced is incinerated. Similarly, in AEB Amsterdam’s W to E plant, which has the best credentials in the world, only about 0.5 kg of residual waste out of 1000 kg of waste remains, which is dumped in a landfill.

In view of this, it is imperative that a number of measures are undertaken to address the problem of landfill sites across the nation:

1. Introduce a specific component in Swachh Bharat 2.0 that provides viability-gap-funding to private players for conceptualizing and implementing projects for treatment of non-segregated waste, including bio-degradable waste, currently lying in our landfill sites. These contracts would include O&M provisions (Operations and Maintenance provisions), wherein till the time waste processing facilities are setup to enable processing of waste to generate compost or energy, scientific practices like covering of landfills with a minimum of 10 cm of soil, inert debris or construction material at the end of each working day or adding an intermediate layer of 40-64 cm thickness of soil pre-monsoon, are undertaken. Additionally, surface run-off water from the landfill sites need to be managed as well to prevent nearby water contamination. Providing a non-permeable lining system at the base and building walls around the waste disposal area should also be undertaken as a part of this O&M service.

2. Dis-incentivise urban local bodies that do not make a shift towards secure and sanitary landfill site management. It is noteworthy that the MSW, 2016 rules clearly outline that landfills should be provided with composite liners to restrict leachate percolation to underground water table. As per the MSW, 2016 rules, "Sanitary land filling " means the final and safe disposal of residual solid waste and inert wastes on land in a facility designed with protective measures against pollution of ground water, surface water and fugitive air dust, wind-blown litter, bad odour, fire hazard, animal menace, bird menace, pests or rodents, greenhouse gas emissions, persistent organic pollutants, slope instability, and erosion. It must be equipped with a proper collecting and ventilating system in order to recover the gases produced. The rules further calls for establishment of common regional sanitary landfill for a group of cities and towns falling within a distance of 50 km (or more) from the regional facility, on a cost sharing basis and to ensure professional management of such sanitary landfills. Stringent implementation of these MSW, 2016 rules itself would be enough to leapfrog our urban local bodies to the new-age landfill-site management practices.

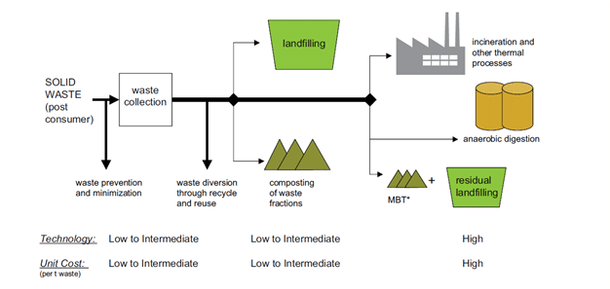

3. Going forward, as we move forward from post-consumer waste to landfill waste treatment and thereafter, the technology gradient as well as unit cost of waste treatment goes from low to high. This is further exemplified in the figure below.

So, waste treatment only becomes more complex technologically and hence leads to higher unit costs while also leading to lower extraction efficiencies as we move forward. In the Indian context, this is further aggravated by the fact that the waste in the landfills currently is not segregated. It makes sense to henceforth develop integrated waste management contracts with entities being held responsible for end-to-end activities right from collection, segregation, treatment and processing as well as Waste-to-Energy plant and landfill-site management.

4. Additionally, multiple incentives should be extended to players in the Waste to Energy domain. So, the report by the Planning Commission herein recommends the following measures:

- Tipping fees, i.e. the charge levied upon a given quantity of waste received at a waste processing facility to offset the cost of opening, maintaining and eventually closing the site, should be levied.

- Higher feed-in tariffs to Waste-to-Energy plants supplying renewable energy; this increases their sustainability.

- Tax Incentives: Waste-to-Energy plants be exempted from corporate income tax for the first five years of operation and eligible for immediate refund of value-added tax.

5. And lastly, to control the methane emissions from the existing landfills, regulations should be enacted as part of our international obligations, wherein the quantity of biodegradable waste in landfills is brought under stricter controls. Under these norms, internal targets should be set for the reduction of biodegradable waste in landfills from current levels of little over 50 per cent to less than 20 per cent by 2025. This should be backed by developing renewable energy credits and bonds and strengthening of the “Clean Development Mechanism”.

With these measures in place, through a renewed Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 (Urban), India can look forward to a much cleaner and healthier urban landscape.

Anand Trivedi and Sumitra K work with the Monitoring and Evaluation office of NITI Aayog.