Ideas

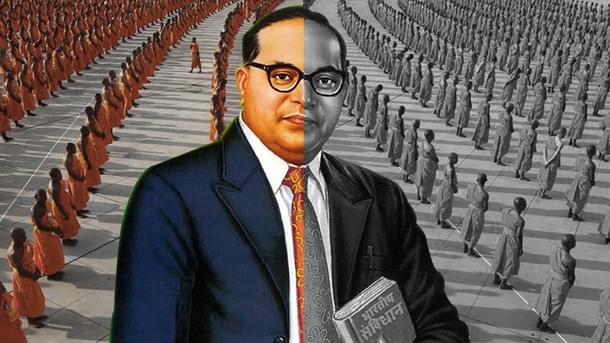

The Ambedkar They Don’t Want You To Know About

Aravindan Neelakandan

Apr 14, 2017, 09:44 AM | Updated 09:43 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Maybe Baba Saheb’s ideas were first ignored and then misrepresented precisely because the intelligentsia knew that those ideas would not fit into the ‘left-liberal’ narrative. Being a prolific scholar and a patriot, Dr Ambedkar recorded his observations on a myriad of topics, events, problems and debates of his times. Here are seven aspects of those which the Old Media and the leftist academic cartel do not want Indians to know about.

1. Dr Ambedkar considered the mahavakyas of Upanishads the spiritual basis of democracy

In his famous speech to the Jat-Pat-Todak Mandal, Dr Ambedkar made the suggestion that Hindus need not look anywhere outside their scriptures to build a society based on the principles of liberty, fraternity and equality. They could look into the Upanishads for those values, he said.

Later in his scathing attack on Hinduism in the book Riddles of Hinduism, he not only revisited the idea but elaborated on it. He took the three mahavakyas—'Sarvam Khalvidam Brahma', 'Aham Brahmasmi', and 'Tatvamasi'—and named their combined purport. He wrote:

To support democracy because we are all children of God is a very weak foundation for democracy to rest on. That is why democracy is so shaky wherever it made to rest on such a foundation. But to recognize and realize that you and I are parts of the same cosmic principle leaves room for no other theory of associated life except democracy. It does not merely preach democracy. It makes democracy an obligation of one and all.

2. Dr Ambedkar considered the Hindu Civil Code the first step towards a Uniform Civil Code.

The same Dr Ambedkar who rejected outright the inhuman and outdated aspects of Smrithi traditions also demonstrated that the same tradition, with all its diversity, could be distilled to create a Hindu law that had prominent space for social democracy and gender justice.

He saw the Hindu Code Bill (HCB) as instrumental in moulding Hindu society into a unitary one based on the principles of liberty and equality. In a lecture delivered on 11 January 1950, he declared:

The present bill is progressive. This is an effort to try to have one civil law for all the citizens under the constitution of India. The law is based on the religious scriptures of the Hindus.

While for Nehru the HCB was perhaps a political device to obfuscate between the Hindu traditionalists and Hindu nationalists, thus making himself the champion of liberal democracy within the Congress, for Dr Ambedkar the HCB was a tool for creating a strong and healthy Hindu society which could become the basis for the modern Indian state.

3. Dr Ambedkar was against giving Indus water to Pakistan without Pakistan acknowledging Indian farmers’ first rights over the river.

British economist Henry Vincent Hodson occupied many key positions in the colonial government as the Director of the Empire Division of the Ministry of Information and Constitutional Advisor to the Viceroy. In his book The Great Divide: Britain-India-Pakistan (1969), he gives a detailed account of how Dr Ambedkar refused Pakistan the Indus water and how Mountbatten intervened on behalf of Pakistan:

At a meeting of ministerial representatives from India and Pakistan on 3rd May (1948), Dr Ambedkar, for India, insisted that no water could be supplied until Pakistan accepted India’s legal claim that all the water belonged to East Punjab, who had the right to do with it as they wished. The chief Pakistan representative, Mr Gulam Mohammed, came to see Lord Mountbatten after the meeting had broken down on this point. The Governor General immediately phoned Pandit Nehru and expressed his disgust that miserable peasants and refugees were being made to suffer when the matter was still under negotiation. Pandit Nehru agreed and undertook to get the conference going again and break the deadlock.

4. Dr Ambedkar wanted Sanskrit to be the national language of India.

As it is now well known, Dr Ambedkar wanted Sanskrit to be the national language of India. The Sunday Hindustan Standard dated 11 September 1949, reported that Baba Saheb, as law minister, wanted Sanskrit to be the official language of the Union. In the Executive Committee of the All India Scheduled Caste Federation, Dr Ambedkar reiterated the same.

Later, when the creation of linguistic states became a burning issue, Dr Ambedkar was in favour of the creation of such states. While he recognised that there was an inherent danger in the creation of linguistic states, he believed that it was a danger “a wise and firm statesman could avert”.

Towards that end, Dr Ambedkar made the following strong recommendation:

The only way I can think of meeting the danger is to provide in the Constitution that the regional language shall not be the official language of the State. The official language of the State shall be Hindi and until India becomes fit for this purpose English. ... Since Indians wish to unite and develop a common culture it is the bounden duty of all Indians to own up Hindi as their language. Any Indian who does not accept this proposal as part and parcel of a linguistic State has no right to be an Indian. He … cannot be an Indian in the real sense of the word except in a geographical sense.

This recommendation goes beyond recommending Hindi as the official language. It also recognises the need to develop India as a culturally united nation-state. It also rejects the territorial conceptualisation of nationhood and advocates strong cultural nationalism as the basis for nationhood ‘in the real sense’.

5. Dr Ambedkar wanted an Indian army free of the preponderances of elements hostile to India.

In his mercilessly objective analysis of the demographic nature of the pre-Partition Indian Army, Dr Ambedkar showed how the Indian Army in the north-western region of India was having a very high proportion of Islamists. He exposed as false the British reasoning that it was because the North-Western province Muslims were martial races while most of the Hindus were not. He stated that it was actually the rebellion of “1857 which was the real cause of the preponderance in the Indian Army of the men of the North-West” and not the so-called martial and non-martial classes theory, which termed “a purely arbitrary and artificial distinction”.

Pointing out the gross inequalities and inherent insecurities against the Hindus in the pre-Partition Indian Army, Dr Ambedkar wrote about the need for “getting rid of the Muslim preponderance in the Indian Army”.

The bulk of this amount of Rs. 52 crores which is spent on the Army … is contributed by the Hindu Provinces and is spent on an Army which for the most part consists of non-Hindus! How many Hindus are aware of this tragedy? How many know at whose cost this tragedy is being enacted? Today the Hindus are not responsible for it because they cannot prevent it. The question is whether they will allow this tragedy to continue.

While Dr Ambedkar’s statement about the complete exchange of populations between India and Pakistan as part of the Partition formula is well-known, his views of keeping Indian institutions like the army free of the preponderance of elements hostile to Indian national life is not well-known.

6. Dr Ambedkar viewed with suspicion the missionary support for the movement of 'Dalit' causes.

In his preface to Prof Lakshmi Narasu’s book, the Essentials of Buddhism, he pointed out that the missionary support for social reforms was not because of any real concern but only as a means for proselytisation. He wrote:

That was the era when Christian Missionaries were not only countenancing the social reform movement but viewed it with high favour as marking a half-way house between orthodox Hinduism and conversion to Christianity. It did not take long for them to change their views and look upon such progressive movements as constituting a real hindrance to proselytization.

It is interesting to note that the Collected Works of Dr. Ambedkar (Vol-17) also includes a letter written to Dr. Ambedkar by Babu Jagivan Ram, another tall leader of the Scheduled Communities. This letter was from the files of the British CID of Bihar province and is part of a Special Officer’s report, dated 9 March 1937.

Addressing Baba Saheb as ‘my dear Doctor Saheb', Babu Jagajivan Ram cautioned against one 'Mr Baldeo Prasad Jaiswal of Allahabad'. “No person of Bihar is with him. He has his office located in a Catholic Church here and everything is being manoeuvred by missionaries”, wrote Babu Jagajivan Ram and went on to point out that “he will not be able to have a gathering of more than one hundred Depressed Classes”. “He can, of course, invite thousands of Muhammamidans and Christians as he did at Lucknow. I take strong objection of this method. We should have genuine Depressed Classes conferences”, so the letter concludes.

The letter shows that both the leaders were averse in principle to the missionary meddling in the movements of Scheduled Communities. That the letter ended in the files of the British CID also shows an interest or involvement of the colonial government against them.

7. Dr Ambedkar wanted the Indian state to run an Indian Priest Service for Hinduism.

In his work, Annihilation of Caste, Dr Ambedkar wanted the state to create a body of Hindu priests in the line of civil services. Priesthood would ‘cease to be hereditary’ because of this, he believed. According to him, every Hindu must be eligible for being a priest. The examination for Hindu priesthood, he believed, should be ‘prescribed by the State’. ‘No ceremony performed by a priest who does not hold a sanad shall be deemed to be valid in law, and it should be made penal [=punishable] for a person who has no sanad to officiate as a priest.’

Further he stated that ‘the number of priests should be limited by law according to the requirements of the State, as is done in the case of the I.C.S.’

Though at the outset it definitely looks like and most probably is unjustifiable to have state control over religious matters, this also effectively makes the state the patron of Hinduism. If Indian state is to establish a corruption-free, Hindu Priest Service body, which constantly updates and adapts itself to the changing situations, then nothing can be more desirable to political Hindus than such a body of Hindu priests.

Interestingly, this dream of Dr Ambedkar may be realised through a most practical scheme of the Madhya Pradesh government.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.