Ideas

The Other Jauhars: Purabiya Rajputs And The Three Jauhars Of Raisen

Kamalpreet Singh Gill

Dec 23, 2017, 08:25 PM | Updated 08:25 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

,_1567.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

,_1567.jpg?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

Few medieval rituals fascinate and confound the modern mind as the jauhar. Undertaken as the final act of defiance of a warlike people in the face of certain defeat against a vastly superior enemy, the jauhar shocks our modern sensibilities to the extent of almost appearing reprehensible.

A ritual in which women voluntarily immolate themselves to avoid capture at the hands of the enemy, and its accompanying rite of Saka where the men rush to battle, sword in hand, determined to die fighting against hopeless odds, has few parallels in the history of mankind. And yet, as any historian worth his salt would agree, the jauhar and the Saka were far from exceptional instances in Indian history.

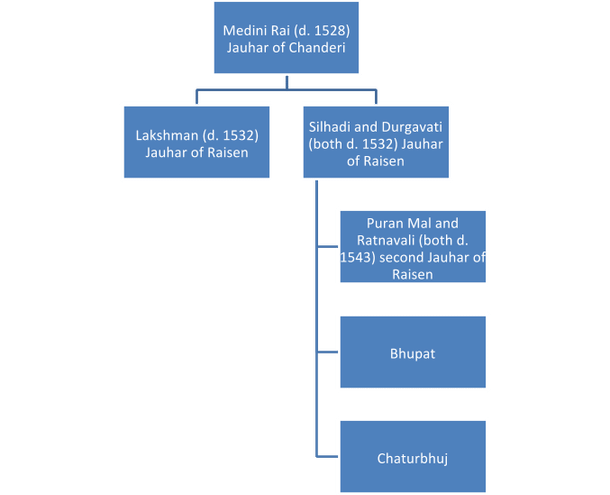

The bloody saga of our history is littered with such acts of exceptional valour. While the three jauhars of Chittor and the jauhar of Ranthambore have been etched into the annals of Indian history, relatively lesser known are the three jauhars of Raisen, despite being witnesses to tales of unmatched valour and courage by the men and women who lived through those turbulent times.

The Purabiya Rajputs of Raisen

Situated in the heart of the Malwa plateau in central India, Raisen and the town of Chanderi were witness to the struggles of an eastern branch of Rajputs for sovereignty and honour in the early sixteenth century. This was a time when the northern part of the Indian subcontinent was facing a four-way struggle for power between the Rajputs, the ruling Lodi Afghans, the Sultanates of Gujarat and Malwa, and the newly arrived Mughals.

The Purabiya Rajputs of Raisen and Chanderi

Medini Rai

Medini Rai was the head of an eastern branch of Rajputs who emerged as important power brokers in the Malwa region around Ujjain. Known as the Purabiya or Ujjainiya Rajputs, these men became increasingly important players in the affairs of the two most important powers in central India – the Malwa Sultanate, ruled by the Khilji Afghans and the Gujarat Sultanate, founded by Tanka Rajputs who had converted to Islam.

As the two Muslim Sultanates fought for supremacy over the fertile tracts of central India, each eagerly sought the services of the Purabiya Rajputs led by Medini Rai. Preferring to ally himself with the Sultan of Malwa, Rai became his most powerful chieftain and, with time, had begun to claim for his Rajputs a status equal to the other Muslim noblemen in the Sultanate of Malwa. This put the sultan in a difficult predicament. While on the one hand he almost completely relied on the Rajputs to prop up his Sultanate, on the other, the ulema or the Muslim clergy was strictly against giving a Hindu the same status as that enjoyed by the Muslim Amirs.

In 1526, Rai served with Rana Sanga in the Rajput confederacy against Babur at the Battle of Khanwa. After the defeat of the Rajputs, Rai returned to his strongholds in Malwa. Babur, shaken by the stiff resistance he faced from the Rajputs at Khanwa, decided to break their power by isolating them. In 1528, he laid siege to Rai’s stronghold of Chanderi. Babur attempted to win over Rai by offering him the opportunity to serve under him, which the Rajput promptly rejected. At the end of a bitterly fought battle, Rai and his brave band of Rajputs, finding themselves vastly outnumbered by the Mughal troops, made preparations for jauhar. A special fire pit was prepared into which women and children, bedecked in their finest, leapt, while the men, clad in saffron, rushed to the battlefield to fight until death.

Durgavati and Silhadi

The saga of Rani Durgavati and Silhadi matches that of Padmini and Rana Ratan Singh for valour and sacrifice. Silhadi was a contemporary and, by some accounts, possibly a relative of Rai’s. Together, the two men had acted as the main power brokers in Malwa, toying with the Sultan at will and eventually causing the collapse of his Sultanate when they decided to withdraw their support. In addition, Silhadi was also related to Rana Sanga of Mewar, with the latter marrying one of his daughters into Silhadi’s household while Silhadi in turn fulfilling his obligations as a clansman by joining the Rajput Confederacy led by Rana Sanga at the Battle of Khanwa.

After the collapse of the Malwa Sultanate, Silhadi and his band of Rajputs were wooed by the Sultan of Gujarat, Bahadur Shah, who invested them with great gifts of elephants and gold, recognising their value as warriors and power brokers. However, soon enough, like Rai had done with the Sultan of Malwa, Silhadi began to insist that the Sultan of Gujarat – now the most powerful ruler left in north India – accord his Rajputs the same status as the Muslim aristocrats of the Sultanate who held the title of Amir. For Bahadur Shah, this was deeply problematic, as in a theocratic Muslim state, the Amir was a pillar of Islamic rule and by certain strict interpretations of Islamic law, an unbeliever could not be accorded the same status and peerage as the Muslim Amirs.

However, an even bigger problem was presented by the presence of Muslim women in the harem of Silhadi. How these women came into the harem of the Purabiya Rajput warlord is not clear, but what has been documented by historians is the sheer amount of resources that went into supporting the luxurious lifestyles of these women. The Mirat-i-Sikandari, a history of the Gujarat Sultanate for instance, mentions that the

expenditure in Silhadi’s household on women’s dresses and perfumes exceeded that in any other king’s palace. All the women’s clothes were of gold brocade or embroidered with goldNaukar, Rajput and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labor Market in Hindustan

For the Gujarati ulema, this became the chief sticking point. Since the Sultanate was by definition a theological state deriving its legitimacy from Islam, and the Sultan, as the regent of Allah, was by law bound to uphold the principles of Islamic law within his dominions, this created a dire situation for Bahadur Shah. On the one hand, he needed the Rajputs as warriors par excellence in his service, while on the other hand, defying the ulema would mean losing the theological legitimacy underpinning his rule. Ultimately, the Sultan gave in to the demands of the ulema, and decided, in the words of the author of Tabaqaat-i-Nasiri,

that he should release the Musalman women from the disgrace of the kufr (heathenism) and the wretchedness of the slavery of the Kafirs.ibid

The result in the end was that Bahadur Shah invested the Rajput stronghold of Raisen with this troops, where Silhadi and his brother Lakshman were held up with their band of followers and their women. As the end came near, it was Rani Durgavati, Silhadi’s wife who exhorted the Rajputs towards the right path, which she proclaimed was that of bravery and jauhar. In the end, Silhadi, along with his brother Lakshman, sallied forth with their band of brave Rajputs to fight the invading Sultan while the women in the fort committed jauhar. Thus, in the Rajput way of life, honour – and the right to be treated as the equal of even the highest lords of the land – was reason enough for a Rajput to give his life for.

Bhaiya Puran Mal

Bhaiya Puran Mal’s story represents perhaps one of the most treacherous tales of betrayal in the annals of Indian history.

Bhaiya Puran Mal was the son of Silhadi who, after serving in the Mewar army as a youth, returned to his ancestral stronghold of Raisen where his clan had restored itself to their status of being the pre-eminent power brokers in central India. Meanwhile, in north India, Sher Shah Suri had evicted Humayun and styled himself the emperor of India. In reality though, this meant that Sher Shah would need to win the allegiance of all the local warlords and in north and central India.

Bhaiya Puran Mal, as the leader of the Purabiya Rajputs, was the most important warlord in central India. Recognising his importance, Sher Shah asked for the allegiance of Puran Mal, in return presenting him with a 100 horses and a 100 splendid robes of honour. However, within a few years, the alliance turned sour. As had happened in the time of his father, the ulema at the court of Sher Shah began to feel uneasy with the presence of Muslim women in the harem of Bhaiya Puran Mal. After Puran Mal annexed the Muslim-held town of Chanderi, the ulema wasted no time in issuing a fatwa against Bhaiya Puran Mal for keeping Muslim women in his harem and proclaiming death as the punishment for the crime. It was indicative of the skewed structure of power relations between the two groups, that while Muslims could, and as a matter of right, demand Hindu women either in marriage or to be kept in their harems, the presence of a Muslim woman in a Hindu household was reason enough for the ulema to issue a fatwa for death.

In 1543, Sher Shah’s troops invested the fort of Raisen and Puran Mal’s Rajputs braced themselves for a long siege. However after six months, and tired of the endless siege, Qutub Khan, a prominent Afghan noble in Sher Shah’s army, gave the assurance of safety to Puran Mal and his family were there to surrender. Taking the Afghans for their word, Puran Mal came out of the fort with a handful of his followers and their families, and camped at a place allotted to them by Sher Shah. Surrounded on all sides by Afghans, Puran Mal trusted the word of Qutub Khan, who had sworn an oath on the Quran to ensure the safety of Puran Mal and his men.

For a few days, the Rajputs camped in peace, but when Sher Shah was reminded of the fatwa issued by his ulema, he ordered his elephants to be prepared. At this moment, the Rajputs realised that their fate was sealed. At the crack of dawn, Puran Mal entered his tent and severed the head of his beloved wife, Ratnavali, who was renowned as an accomplished poetess, and ordered his Rajputs to do the same. Preferring death to dishonour, the Rajput women stood up, embracing death at the hands of their fathers, brothers, and husbands than be captured by the enemy. As the Afghan troops fell on them, the Rajputs fought gallantly, like “hogs at bay”, but they were cut down by the Afghans and trampled by the elephants. (Cambridge History of India, Vol 4, Pg 53). One daughter of Puran Ma,l who escaped the camp along with three of her brothers, was captured by Sher Shah and sold off to a rope dancer to make her dance in the market, while the three surviving sons of Puran Mal were castrated. (Kolff: 106)

Rajputs: The Warrior Ascetics

What drove the Rajputs to such extremes of actions? From being imperial warlords and wealthy chieftains to staking their lives for the sake of mere titles, what passion drove the Rajputs to have so little regard for life and its pleasures?

The historian Dirk H.A. Kolff, in his celebrated study of Rajput identity titled Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy : An Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market in North India, 1450-1850, offers us some clues. Kolff contends that in early medieval India, warrior hood and asceticism were not exclusive of each other. The early Rajputs still retained much of their nomadic origins and thus settled life and the pleasures that came with it were looked at with suspicion, even contempt. The preferred way of life instead, being one spent looking for a king to fight for. For the Rajput, Shiva – the warrior-yogi par excellence - was the ideal of manhood to be attained. Evidence of this can be gleaned from oral and literary traditions of the period. An enduring Rajput legend is that of Rana Samarsi, a Rajput chieftain who lived in the late 13th century. It was said that he was the ‘Regent of Mahadeva’ and that a ‘simple necklace of the seeds of the lotus adorned his neck, his hair was braided and he is addressed as Joginder, the king of ascetics.’.

Thus, kingship and asceticism were, to the early Rajput mind, two sides of the same coin, and to make the transition from one to the other, would not appear as shocking to the early medieval warrior as it would to the modern mind.

Another Rajput chronicle is the Prithviraj Raso, an epic Brajbhasha poem composed sometime in the early sixteenth century. Here, a Rajput warrior goes to battle with a

coil of matted hair on his head, a musical horn in his hand and ashes of cowdung smeared on his body. His ensigns were a battle axe, a trident, and a leather cloak. In short, ‘he was altogether like Hara (Siva), the destroyer of all’.ibid

This tradition of association with Shiva, the warrior ascetic supreme, has been preserved down to this day and can be witnessed at many erstwhile Rajput strongholds. The Rana of Mewar, for instance, derives his authority as the chief of all Rajputs from Mahadeva, the isht-devta of the Rajputs of Mewar. To this date, the ruling family of Mewar pays obeisance to the temple of Eklingji situated a few kilometres north of Udaipur. The pomp and exuberance, including the luxurious palaces and the games of polo, are later additions to the Rajput way of life, adopted once the Rajputs and the Mughals, each having exhausted the other after centuries of bloodshed, finally settled into an uneasy but working relationship. For the early Rajputs however, the tradition of asceticism meant that death was not an event to be feared. Like their deity, Mahakaal, they perhaps believed it to be a harbinger of new beginnings in a cycle that stretched to eternity.

Note: This article is based on Dirk Kolff’s Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labor Market in Hindustan, and The Cambridge History of India, Vol 4 The Mughul Period, edited by Sir Richard Burn.

Kamalpreet Singh Gill is a regular contributor to Swarajya. His areas of interest include history, politics, and strategic affairs. He tweets at @KPSinghtweets.