Ideas

Where Do The Solutions To Delhi’s Air Pollution Problems Lie? (Hint: Not Delhi)

Srikanth Ramakrishnan

Nov 10, 2016, 11:41 AM | Updated 11:41 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

This is festival time in India. Both Dussehra and Deepawali, or Diwali, were only recently celebrated with much fanfare. Naturally, it’s the best time of the year to be in Delhi. But, let’s not forget, it’s also the worst. The best, because, well, it’s festive season, and that comes with fireworks, lights, mouth-watering sweets and more. The worst, because it’s winter and that’s when Delhi’s pollution is at its peak.

Diwali is that time of the year when firecrackers are blamed for the unbearably high levels of pollution. Several reports doing the rounds recently have said Delhi’s pollution was up fourteen times than usual, with many blaming Diwali especially for it. Of course, crackers do cause pollution, and many of us Hindus who observe Diwali don’t really burst loud crackers, sometimes not at all, but for different reasons.

The story of Delhi’s pollution is not new, though. The capital continues to be the most polluted city in India, and was ranked the most polluted city in the world by PM 2.5 standards in 2014. During the winter of 2015, a report showed that Delhi’s pollution levels peaked at 442 in PM 2.5 standards. Delhi’s pollution had gone so out of hand that Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal launched his ill-fated Odd-Even scheme, which was a flawed plan to begin with.

Understandably, Delhi’s pollution problem isn’t really linked to vehicles. According to an IIT Kanpur report, 46 per cent of the vehicular pollution is created by trucks in the city when it comes to both PM 10 and PM 2.5. Two-wheelers contribute to 33 per cent of the pollution, and 10 per cent is contributed by four-wheelers. Buses contribute to 5 per cent of the pollution, whereas 4 per cent is by light commercial vehicles. The rest comes from three-wheelers and other factors.

So then, where does Delhi’s air pollution come from if not fireworks or vehicles?

The National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), along with researchers from Austria-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIAS), conducted a study, whose results revealed an important thing: The majority of the pollution came from outside of the National Capital Territory (NCT), from other regions in the NCR in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana. Therefore, no matter what stringent standards Delhi adopted, pollution would flow in from the neighbouring states in any case.

The first step in reducing Delhi’s pollution would be to push for better standards across both Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, but that seems to be a distant dream, especially in the case of the latter. The study also revealed that some of Delhi’s pollution came from as far away as Pakistan, but the converse is also valid; pollutants from India also cross over to Pakistan with the wind.

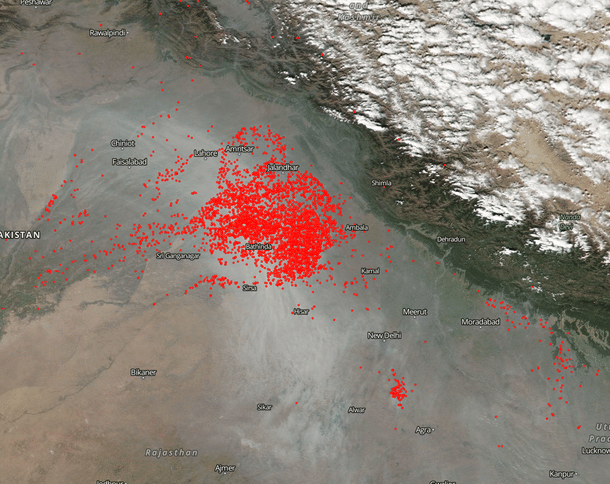

A NASA forecast (pictured above) from 1 November shows that there was an upward spike in the number of ‘fires and thermal anomalies’ in the vicinity, mostly in Punjab and northeast Pakistan. These fires are the result of farmers burning crop stubble in Haryana, Punjab and parts of Pakistan as well. Tonnes of straw are set on fire to clear the land for growing the winter crop. The smoke emanating from these crop fires contributes to more than a quarter of the pollution in North India and Pakistan.

The NASA Earth Observatory, on 1 November released a satellite image (shown below) of the smoke in North India spread out mostly over Punjab and parts of Pakistan and parts of it over New Delhi.

Another cause of pollution in Delhi is the landfills. Delhi has four landfills, or garbage dumps, at Bhalswa, Ghazipur, Okhla and Narela-Bawana. Barring the fourth one, the rest operate at well over their capacity. With 9,000 metric tonnes of garbage being produced every single day, these three landfills have accumulated enough garbage to reach heights greater than 40m, almost half the height of the Qutub Minar, which stands at 72.5m. While Okhla has an operational unit to convert waste to energy, Ghazipur and Narela are still under development.

The Bhalswa landfill caught fire in April 2016, which lasted for a whole three weeks. The Delhi Pollution Control Board sent a notice to the municipal corporations saying it had received complaints from residents and the GNCTD that garbage was being burned at these sites. The garbage dump should have been shut down in 2006 after it crossed all permissible limits of accumulation, but a decade on, it still operates, catching fire every now and then. The GNCTD, led by Kejriwal, did the most expected thing: allege sabotage by the Bharatiya Janata Party-led municipal bodies to derail its failed Odd-Even scheme.

The truth is that a landfill does not need to be set on fire in order to burn. No manual intervention is needed to cause fires. Landfills are a melting pot of domestic, industrial and medical wastes. Biodegradable waste, combined with other toxic chemicals, decompose, releasing heat in the process. This can cause flammable garbage to catch fire. The chemical reaction is spontaneous. The formation of methane during the decomposition further adds fuel to the fire, literally, while also polluting the environment.

In January 2016, a fire broke out in Deonar, Asia’s largest dumping ground, located in Mumbai. Images from NASA’s Earth Observatory showed smoke spreading across South Mumbai, aided by the winds. The same would apply to Delhi, except the smoke engulfs the neighbouring cities and states and spreads out to Pakistan rather than the sea.

The solution for this would have to be a long-term plan involving all the cities and states in North India, with the centre coordinating the efforts.

With Delhi High Court already having directed the states of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan to strictly enforce a ban on the burning of paddy stubble and holding the chief secretaries of the states responsible, the government must encourage farmers to take up conservation agriculture on a large scale. Paddy stubble is burnt in order to clear the fields to sow wheat. Burning them is less time-consuming than transporting them to a government power plant, which is also economically impractical for many. The Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), along with Punjab Agricultural University, has advocated several practices to prevent the burning. (More about conservation agriculture here). A decade ago, farmers from East Washington in the US had advocated several measures in crop rotation to prevent burning of crop stubble.

Coming back to the garbage issue, a lot needs to be done. For this, the GNCTD will have to do the inevitable – coordinate with the municipal corporations and the centre. Waste needs to be segregated at its source, right from the doors of various households to the waste management units of industrial units and hospitals. Biodegradable waste needs to be transported to treatment plants, and not landfills, where they can be treated, converted to energy, since the process of decomposition will continue to take place. This energy can then be sold or supplied to power streetlights, or used for any other purpose. This will also help solve the capital’s power problems, which have been on the rise after the current government’s promise of free power. Non-biodegradable waste must be sorted and sent to recycling units, rather than be allowed to mingle with biodegradable waste.

The last of all the major contributors to Delhi’s pollution is the use of wooden stoves. A fact sheet from the New Hampshire Department of Environment Sciences says that wood fires release over a hundred potentially carcinogenic pollutants. Providing low-income households with LPG connections has already been initiated by the Oil and Petroleum Ministry under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana. Once standards have been set for the NCT, they must slowly be extended to other areas in the vicinity, such as Gurgaon, Faridabad, Ghaziabad and Noida. The same process then needs to be implemented across other cities in North India where climatic conditions are similar.

What’s important to remember is that while other cities are key stakeholders in Delhi’s pollution, Delhi itself is also part of the pollution problem.

Systematically identifying and then eliminating or minimising sources of pollution, one by one, is key to solving Delhi’s toxic air problem, and not stop-gap measures like banning vehicles without prior arrangements.

Srikanth’s interests include public transit, urban management and transportation infrastructure.