Infrastructure

View From Above: How Drones Are Surveying Land In Rural India Under SVAMITVA

Ankit Saxena

May 26, 2025, 01:46 PM | Updated Jul 01, 2025, 09:24 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Thirty-one-year-old Vinod lives in his ancestral home in Bheemwala village of Dehradun, Uttarakhand. Until two years ago, he was caught in an encroachment dispute with government authorities. The problem started because there was no formal documentation of the ownership of the home.

Like all other properties in his village, Vinod had no official papers to prove the exact boundaries and ownership of the property.

“Our home was passed down from generations, but we never had any registered documents. My father suffered on the same count. At one point, the house was also marked for demolition,”, Vinod says.

Land disputes are one of the biggest reasons for case backlogs in Indian courts. According to previous reports, about 25 per cent of Supreme Court judgments involve land disputes.

A World Bank study also found that 66 per cent of all civil cases in India are about land or property — related to unclear land titles, ownership issues, and outdated records, which can take up to 20 years to settle.

With roughly two out of every three pending civil cases related to property, efforts had been made earlier to fix the issue of poor land records. But due to the scale and complexity, real progress was not possible without a major on-ground effort to accurately map and record land ownership across the country.

In Vinod's case, the solution came from a little above the ground.

In 2023, a land survey was carried out in his village using drones. “It was the first time we saw a drone, which was flying over our homes. We had no idea how a drone, and its technology would help us then,”, he adds.

The drone survey was conducted under the Government of India’s SVAMITVA (Survey of Villages Abadi and Mapping with Improvised Technology in Village Areas) scheme — which uses drones to accurately map rural properties and issue legal ownership documents.

For Vinod and his father, Late Shri Mamchand, a long and stressful land dispute finally ended in their favour — thanks to the drone survey.

The precise demarcation of their land finally led to the issuance of a property card under the SVAMITVA scheme. His father submitted the new documents as evidence to the High Court of Uttarakhand, which the court accepted and ordered the demolition notice to be withdrawn.

While drone technology and India’s drone capabilities made headlines recently after its key role in the success of Operation Sindoor, India’s homegrown drones, have been serving equally well in another important area — mapping rural land across the country.

The surveys carried by this specific type of drone has helped not only Vinod’s village in Dehradun but also more than 5,000 villages across states like Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Gujarat, Karnataka, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh.

The drone mentioned here was a “Stargedge” drone, developed by Delhi-based company Hubblefly.

But it is not just Staredge. Multiple drone companies from Delhi, Bengaluru, and Mumbai are part of this initiative. Drones provided by ideaForge, AEREO (Aarav Unmanned Systems), Aesteria were also used.

“In 2019-20, the Survey of India began a big round of drone purchases, focusing mainly on drones for land mapping,” says Somil Gautam, General Manager at ideaForge, while speaking to Swarajya.

“They mostly needed two types—micro drones (250gm-2kgs) and small drones (2kgs-25kgs). For rural inhabited (Abadi) areas, with areas of less than a square kilometre, micro drones were used.” he adds.

IdeaForge’s two drones - Q4i Micro (RYNO) model and Q6, designed and developed in Mumbai—were also widely used under this scheme.

How It Started

Land surveys in India have always been slow and difficult, especially in rural India, where unclear boundaries between properties and missing records have caused problems for decades.

“Since colonial times, small land parcels used by villagers for habitation — known as abadi land — were mostly ignored [for records]. The focus back then was on agricultural land because it could generate revenue,” Alok Prem Nagar, Joint Secretary, MoPR tells Swarajya.

“As a result, these small parcels and the houses built on them were never properly surveyed or regulated.”, he adds.

However, with time, the absence of proper land records became a serious problem — both for the people and the government.

Without proper documentations, the government remained unable to collect property taxes or plan improvements in these areas. It has also led to several disputes, including many disputes over encroachments on government land.

For the people, it meant they had no official proof of the land or homes they had lived in for years, making it difficult to resolve disputes or claim their property as an asset.

“Disputes remain a major issue because of this gap. There are cases where, after the husband dies, his widow is forced out by other villagers/family who claim the property — simply because there are no documents. Encroachment on government land is another challenge. Without proper surveys, there no way to clearly show who owns which house, or how much land.”, Nagar tells Swarajya.

Since most of the issues involve completely unregistered land, these disputes are usually internal, within families or at the village (gram) level, and are either handled locally or remain unresolved for years.

The SVAMITVA scheme was launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 24 April, 2020, with the aim of solving this problem and giving legal ownership documents to people living in village homes. It is a joint effort by the Ministry of Panchayati Raj (MoPR) and the Survey of India (SOI).

“The attention [to the problem] came with small villages in Maharashtra that were struggling with incorrect tax assessments because there was no record of precise land boundaries. In 2019, SOI made use of drone technology to map the abadi (residential) villages,”, Nagar tells Swarajya.

“In the same year, during a meeting of the Council of Ministers, the Prime Minister also asked for new ideas and problem areas to focus on. That’s when the then Panchayati Raj Minister shared this small-scale project from Maharashtra and its positive results.”, he adds.

“Seeing the impact and the Prime Minister’s interest in scaling it nationally, the SVAMITVA scheme was developed during the COVID year and officially launched on 24 April, 2020. It began as a pilot program in seven states from northern, central, and southern India.”

As the survey progressed, around 1 lakh property cards were also prepared by October 2020.

Five years of SWAMITVA Scheme

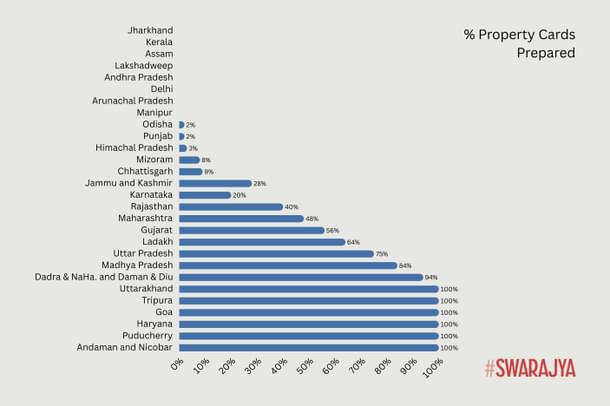

The scheme completed five years in April 2025. As of May 2025, drone surveys have been done in 3.22 lakh villages out of the 3.45 lakh villages notified under the scheme.

Since the launch, 10.46 crore land parcels have been digitised, while 2.54 crore property cards have been prepared for 1.67 lakh villages, giving people formal ownership of their land and homes, according to the latest data from the Ministry of Panchayati Raj.

Today, like Vinod, many people across states have resolved land disputes through property cards and accurate boundary markings.

According to government records, more than 90 per cent of the total budget for the scheme is specifically for technology.

How Drone Technology Powered The Surveying

There are three ways of surveying land for government record purposes- ground, aerial, and satellite.

Ground surveys face many challenges — from the time taken to cover large areas, to the skill of the surveyors, and errors caused by manual work.

“In rural areas, land is a very sensitive issue. Sometimes locals don’t support the survey teams. Often there’s pressure to mark plots in a certain way, which causes problems,” a drone mapping team member tells Swarajya.

“For these reasons, traditional ground survey methods haven’t proven very effective, also considering the time for covering massive areas”, he adds.

For aerial and satellite surveys, precision remains a key issue. While they can create images and large-scale maps covering several kilometres, the accuracy is not enough for creating property records of rural land-holdings. Rural settlements, especially homes, require accurate measurements in meters and even centimetres.

“Even a small change in alignment could mistakenly include neighbouring property, which can cause serious disputes. We all know how sensitive land matters are in terms of ownership and family arrangements.”, he adds.

Thus, there was a gap in aerial surveying and this is where drone technology came in.

For example, the Staredge drone can fly for 35 to 45 minutes and cover up to 1 square kilometre per flight. It can carry a payload up to 4.35 kg and operate up to 1 km away.

Similarly, ideaForge’s Q4 RYNO offers a flight time of around 40 minutes with a range of up to 4 km, while the Q6 can fly for 60 minutes and reach up to 5 km. RYNO is capable of an area coverage of 1 Sq km while Q6 covers a larger area of 2 Sq Km in a single flight.

To put this in perspective, surveying 1 square kilometre on the ground would take at least 15 to 20 days with a team of 3-4 people. With drones, the same task can be completed in just a few hours.

“When we started designing and developing our product, the instructions on precision were clear: our RGB drone needed to achieve less than 10 cm accuracy on the X,Y axis, and 20 cm on the Z-axis.”, Chirag Sharma, CEO of Hubblefly tells Swarajya.

“Moreover, there was special focus on PPK (Post Processed Kinematic) for accuracy, as well as required range and coverage.”, he adds. (PPK is a method to correct for errors during data recording by a drone).

Further, it was not just one kind of area that needed surveying— India’s rural regions vary widely in topography, terrain, weather across states. Drones enabled a unified way to gather all the needed data.

The surveying process also included setting up 567 CORS stations (Continuous Operating Reference Stations).

The CORS network also helps set up Ground Control Points (GCPs), which are physical markers on the ground with exact locations. Having many stations makes the data more accurate by double-checking positions and avoiding mistakes from just one station.

Here is how the survey works:

--After signing a bilateral agreement between the state government and the Survey of India, the state picks the villages to be surveyed and officially announces the survey under the relevant laws.

--Revenue Department staff are trained for the ground work, and village councils (Gram Panchayats) are informed about the survey process.

--Locations for CORS stations and Ground Control Points are selected by SOI teams.

--A village meeting (Gram Sabha) is held to identify the area to be surveyed.

--Before the drone survey, property boundaries are marked on the ground with white lines (chuna lines), usually with the bhagidari of the residents to avoid disputes.

--On the survey day, drones fly over the area to capture images.

--The images are processed into detailed maps at a scale of 1:500, with accuracy up to 5 cm.

--These maps are handed over to the state government to assign correct owner names and verify the details on the ground.

--After verification, the updated maps go back to SOI to include corrections.

--Finally, these maps are used to create property cards for individual owners.

--These maps are further being used for better village planning and management.

According to an industry expert, around 500–600 drones were used for this work across the country.

While the number of drones may not seem very large from an industry perspective, this fleet managed to map around 68,122 square kilometres with high precision, and generate a vast volume of data.

In one drone flight, device is able to accurately capture individual house boundaries, as well as community assets like roads, ponds, canals, schools, Anganwadis, health centres, and open spaces.

The Impact on India’s Drone Industry

Going back a decade from the current use of drones, these devices were primarily used for defence and surveillance.

Smit Shah, President of Drone Federation India, tells Swarajya, “In 2014, there was a blanket ban on the use of civil drones in India, which severely limited any commercial or private use of drones.”

“But with growing interest and applications, the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) and the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) launched Digital Sky and a regulatory framework in 2018. Digital Sky is an online system for managing unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in India.”

It was only in 2021, when the ‘Drone Rules 2021’ were introduced — that the drone market was liberalised. These rules opened up the sector to private players and allowed encouraging innovation beyond defence and surveillance uses.

The Drone Rules 2021 came out, and the SWAMITVA scheme on a national level began in April 2021, after its pilot phase in 2020.

For companies like ideaForge, the scheme created a crucial opportunity to apply and improve its drone technology. Their existing Q4i Micro (RYNO) drone was adapted to meet the project’s requirements, which helped the company further refine its product.

“The specific benchmarks were set for all domestic companies,”, Somil tells Swarajya.

“These benchmarks pushed companies to enhance their drones' capabilities. Today, these benchmarks have become industry standards for new developments.”

In the early stages, components like cameras (often from Sony) and sensors, which were not manufactured in India, had to be imported.

“However, all drones had to qualify as Class 1 suppliers, meaning at least 50 per cent of the components had to be indigenously sourced. Today, we have reached about 70 per cent indigenisation,” Somil adds, while highlighting that the entire design and software development, including for imported parts, was done in-house.

“It is also important to see that this progress was driven during the COVID period, when importing components was extremely difficult. That also gave a push to develop alternatives and strengthen our local ecosystem.”

Further, companies like Hubblefly were established around this time and began manufacturing survey drones as the market demand grew.

“We started Hubblefly as a drone manufacturing company in 2020-21 and began the design and development of drones,”, Chirag Sharma, CEO of Hubblefly, adds.

Hubblefly was among the first five companies in India to be certified by the DGCA for licensed drone operations. Prior to that, the parent company, Drone Destination, focused solely on UAV services and training.

The market demand during that time was mostly for land surveys, and following the market factors, allowed the company to develop drones with specific features to meet those requirements.

Speaking about the product journey, Chirag says, “The frame of the Staredge drone, for example, was developed using carbon fibre, initially outsourcing some parts but progressively moving to complete in-house manufacturing. While motors and propellers were sourced from China.”

“The R&D further continued through real life operations and feedbacks while it was put to use under the scheme.”, he adds.

Developing the drone in-house allowed us to improve its design and performance in ways that the existing drones, mostly DJI, could not match.”

“While DJI drones, have a flight endurance of about 20-25 minutes, Indian manufacturers like Hubblefly, ideaForge and AEREO were able to develop longer endurance platforms, with drones that could fly for 45 minutes to an hour, making them better suited for our surveying grids.”, he adds.

The drone’s capabilities, such as shutter speed corrections, image capture quality, field of view, wind resistance, and stability under varying terrain and weather conditions, continuously improved as they were used extensively for surveying villages.

Since the Drone Rules 2021, the SWAMITVA has been the first large-scale testing ground and a showcase platform to demonstrate India’s growing capabilities in building and utilising drones.

Not Just Technology, Opened Opportunities For Drone Services

When the initial Survey of India (SOI) tender was floated for drone procurement, only three companies were there— ideaForge, a German company, and a startup from IIT Kanpur that supplied five drones.

“But if a similar tender were issued today, at least 10+ Indian companies would be capable of fulfilling the requirements,” Somil Gautam tells Swarajya.

The opportunity did not stop at drone procurement. Being a massive land-mapping project, it also created demand for a range of drone-related services— skilled operators, maintenance, and data management.

“This expanded the ecosystem by generating a new workforce of trained drone pilots and technical service providers.”, he adds.

Initially, after the drone surveys, the SOI was only collecting raw data. However, eventually, it shifted to gather processed data. Drone companies began processing the data and delivering ready-to-use outputs to SOI.

“SOI also floated empanelment tenders, allowing multiple drone and GIS firms to officially offer processed data. This created demand for in-house GIS talent to handle the large volume of data being captured. ideaForge alone supported around 15+ GIS firms to manage this backend work.”, he adds.

One such example is of Vivek Jangir, a mechanical engineer from Rajasthan, who chose this new job territory and trained to be a drone pilot right after graduating in 2021.

Over the last years, he has travelled to several rural regions with a drone to map village habitat areas. Vivek tells Swarajya, “With this drone, I have also surveyed 4-5 villages in a day.”

In the drone industry, companies like Drone Destination, have been training several pilots. It was the first company to launch a training centre for licensed pilot training, following the new drone policy introduced in 2021 that allowed licensing beyond government institutions.

Since then, more than 5,000 pilots have been trained and certified. For the SWAMITVA scheme, Vivek and several other drone pilots received additional training to understand terrain inspection, cultural understanding and interaction with locals, as well as several GIS-based development skills.

He started in 2022, and within just three years, he is now a project manager leading surveying projects and also trains other drone pilots.

“Access to drones and drone-as-a-service were very limited before, but now there has been major progress. Commercial usage of this technology— in agriculture, surveying, and digital twinning— is constantly growing.”, he adds.

What’s next

With this progress, India’s drone industry is now looking ahead at new innovations and expanded use cases.

So far, drones equipped with RGB cameras have delivered high-quality 2D mapping. But this process also opened the doors for development of 3D mapping using oblique and LiDAR cameras—offering millimetre-level precision.

“SWAMITVA also made state governments realise the potential of drone-based mapping at scale. Now, many states are expanding their efforts to map entire regions and even develop digital twins of cities.”, Somil tells Swarajya.

The project helped both drone companies and government agencies recognise the next steps, developing more advanced capabilities for rural, as well as urban planning.

For the same, NAKSHA (National Geospatial Knowledge-based Land Survey of Urban Habitations) programme aims to create and update land records in urban areas.

For instance, a digital twin of Bengaluru is being developed to help the city plan better roads, identify high-congestion zones, and improve tax mapping.

As Vipul Singh from AERO (Aarav Unmanned Systems) puts it, the drone survey and data collection has laid the groundwork for the "Gram Manchitra"—a digital planning tool for villages. Now with enhanced drones to create digital terrain maps, the data is enhancing understanding for cases like — water supply planning, sewage systems, infrastructure forecasting, capturing the varied road data which helps in emergency services and more.

Further, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj is taking forward India’s growth in drones, CORS, and GIS technology for surveying as a model globally. “It will be helpful for countries in Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Oceania, especially where land record systems face similar post-colonial challenges.”, says Alok Nagar.

The data collected has broader uses beyond issuing property cards.

“Through the survey, we have also mapped the total terrace areas in this abadi villages, to be potentially used for solar energy deployment. The Ministry of Renewable Energy is already involved in working on this aspect.”, he adds.

In India, as in around the world, land is source of income, home, store of value, and even a mark or symbol of identity. Yet, even in the 21st Century, accurately measuring and labelling land-holdings was a widespread problem. In such a situation, drones may finally be bringing a measure of clarity from above.